Thirty-six years ago, the American journalist Bill McKibben wrote The End of Nature, the first mass-market book about climate change. The book warned, from the perspective of a lover of nature, about the dangers posed by a warming planet:

“Changes in our world which can affect us can happen in our lifetime — not just changes like wars but bigger and more sweeping events. Without recognizing it, we have already stepped over the threshold of such a change. The rain will still fall, and the sun will still shine. When I say ‘nature,’ I mean a certain set of human ideas about the world and our place in it … More and more frequently, these changes will clash with our perceptions, until our sense of nature as eternal and separate is finally washed away and we see all too clearly what we have done.”

The day that McKibben foretold in his best-selling book, when “we see all too clearly what we have done,” is now upon us. The overheating of the planet is manifesting in increasingly deadly and destructive heat, fire, drought, and storms. These extreme events in turn warn of even harsher, irreversible perils such as the collapse of the Gulf Stream, the vast Atlantic Ocean current that keeps northern Europe habitable.

Yet the climate crisis barely registers in the world’s news coverage. In the U.S., only 37 percent of people say that they hear about global warming in the media at least once a month. In India, the equivalent figure is 53 percent — still only one out of two people, and still only once a month.

As journalists ourselves, the authors of this article sympathize with some of the reasons why climate coverage is getting short shrift. News outlets all over the world face a crumbling business model that has shrunk editorial staffs and intensified workloads. And outlets are understandably preoccupied with the wars in Gaza and Ukraine and overwhelmed by the relentless fire hose of policy shifts and ominous rhetoric coming from U.S. President Donald Trump.

Editor’s picks

But McKibben’s decades of work call upon us to defend reporting on climate change as a critical part of telling the story of the world in which we live. Since publishing The End of Nature in 1989, he has produced more words, with more insights, about the climate crisis and its solutions (see his latest book, Here Comes The Sun) than any other writer: 19 books, dozens of New Yorker stories, and countless magazines pieces and podcasts and blog posts and newsletters.

He has contributed frequently to Rolling Stone, never to greater effect than with his 2012 article, “Global Warming’s Terrifying New Math.” A landmark moment in climate journalism, the article went super-viral back when going viral was a new and genuine achievement and activated a fresh generation of aggressively corporate-focused activists. At the time, Barack Obama was running for a second presidential term and boasting about “drilling everywhere we can.” McKibben’s piece popularized for the first time the concept of a global carbon budget: the maximum amount of carbon dioxide humans could emit before condemning themselves to a catastrophic two degrees of global warming. But the world’s oil, gas, and coal companies were planning to burn five times that much. In factually dense but elegant prose, McKibben concluded that people working to preserve a livable climate had to recognize that their true enemy was not feckless politicians or slothful consumers; it was the fossil fuel industry, for whom “wrecking the planet is their business model.”

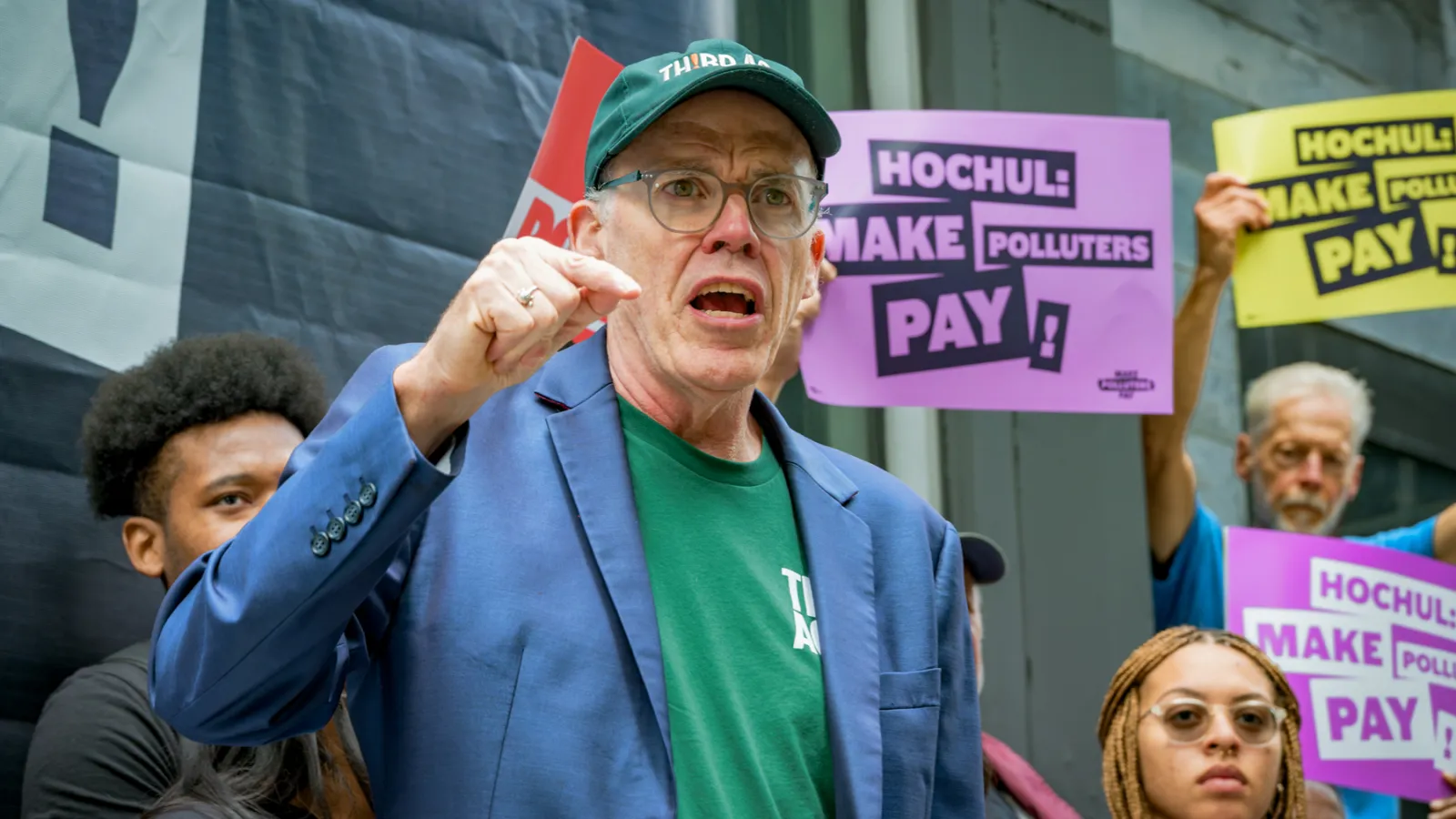

McKibben is the graceful father of modern climate journalism, which is why Covering Climate Now, the global journalism collaboration co-founded by the authors of this article, is honoring him with its first-ever lifetime achievement award. McKibben joins colleagues from around the world, recognized last week as winners of the fifth annual Covering Climate Now Journalism Awards, culled from more than 1,200 entries from every continent. It is not an exaggeration to say that many of those journalists might not be covering climate change if McKibben had not paved the way — demonstrating the power of telling the climate story in a way that resonates.

Related Content

But if McKibben is peerless in his journalistic telling of the climate story, it’s also true that he makes some colleagues nervous.

McKibben is unusual in straddling two worlds that are now more at odds than ever: the world of advocacy and the world of journalism. His founding of the environmental group 350.org, and his role in helping to organize protests against the fossil fuel status quo, have made some journalism traditionalists in the U.S. nervous about embracing him as one of their own. (This, despite a New Yorker pedigree and book sales figures that must make some of those journalists jealous.) Indeed, a wire service reporter told one of us a few years ago: ”You guys need to stop featuring McKibben. He’s an activist, not a journalist.”

In fact, McKibben is both, and it is for his journalism that CCNow is honoring him. But we also hope this recognition by an international journalism service organization like CCNow will prompt a reexamination of the role of advocacy in journalism at this pivotal moment in American history, when First Amendment freedoms and the very existence of democracy and the rule of law are under severe threat.

CCNow was formed at the Columbia Journalism School, where one of us worked and ran the Columbia Journalism Review. While there, we were able to study and reflect on moments in U.S. history when reporters and news organizations were accused of crossing the line into advocacy.

It happened during the Vietnam War, when reporters were vilified for pointing out the lies in Pentagon casualty estimates. It happened during the Civil Rights era, when journalists who reported on protest marches were accused of abetting the movement. It happened during Watergate, when The Washington Post’s Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein were told, by ordinary citizens but also by some news business colleagues, that they had no business taking on a sitting president.

All those stories were criticized at the time as inappropriately veering into advocacy, but they look different in the eyes of history. Nowadays, they are commonly seen as the media doing some of its best work: Telling the truth. Standing up for people without a voice. Holding political leaders to account when they wanted people to look the other way.

The same argument about advocacy has also colored how the media covered the climate story over the years — which was not very much. For too long, climate silence prevailed.

One reason for that silence was that any journalist who simply expressed an interest in covering climate change was suspected of being an advocate, particularly if their reporting mentioned the solution that the world’s climate scientists have repeatedly emphasized: phasing out the burning of the fossil fuels that drives the crisis.

Another reason: Since the 1990s, editors and other newsroom gatekeepers have had their judgment clouded by a disinformation campaign orchestrated by the fossil fuel industry (which borrowed its tactics from Big Tobacco). The timing was tragic: The 1990s and 2000s were the years when ample press coverage and the political engagement it can spark might have averted the trajectory that now has the climate spinning towards breakdown.

Throughout those years, and still today, many in the mainstream press have wrongly evaluated the climate story through the lens of politics, rather than of science. In politics coverage, there is a defensible belief that news reporting should fairly reflect both sides of a given subject — those who favor abortion rights and those who oppose them, those who support lower taxes for corporations versus those who want companies to pay more.

Uncritically applying this maxim to the climate story, however, is a mistake. It led to decades of coverage that gave the same amount of credibility to climate deniers such as former U.S. Senator James Inhofe as it did to NASA scientists like James Hansen, even though only Hansen had the truth on his side.

McKibben was among the first to argue that if we take science seriously, then journalists can’t take a “tell both sides” approach to climate coverage. Physics, after all, does not compromise. Physics imposes its own time limit, which is what makes the politics of climate change different from that of other issues. With health care or tax reform, McKibben explained, advocates can fight for their goals and, if they fall short, come back the next year and fight again. Not so with climate change. Wait too long to stop it, and catastrophe becomes unavoidable: once emissions are in the atmosphere, physics ensures that they will keep overheating the Earth for centuries — a fact that deserves emphasis as world leaders prepare for the UN COP30 climate summit in November.

Trending Stories

Our profession has a lot of catching up to do on the climate story. At a time when too many news organizations — or, more precisely, their corporate owners — are surrendering to government intimidation, McKibben’s example is instructive. We understand why some of our colleagues might be uncomfortable with the activism side of his work. But we see his reporting, and his advocacy on behalf of people who are being savaged by an overheating Earth, as fitting squarely into the arc of history representing the best of what journalism can do. Now, more than ever, his body of work should inspire and motivate us all.

Mark Hertsgaard and Kyle Pope are co-founders of the global journalism collaboration Covering Climate Now.