Copyright truthout

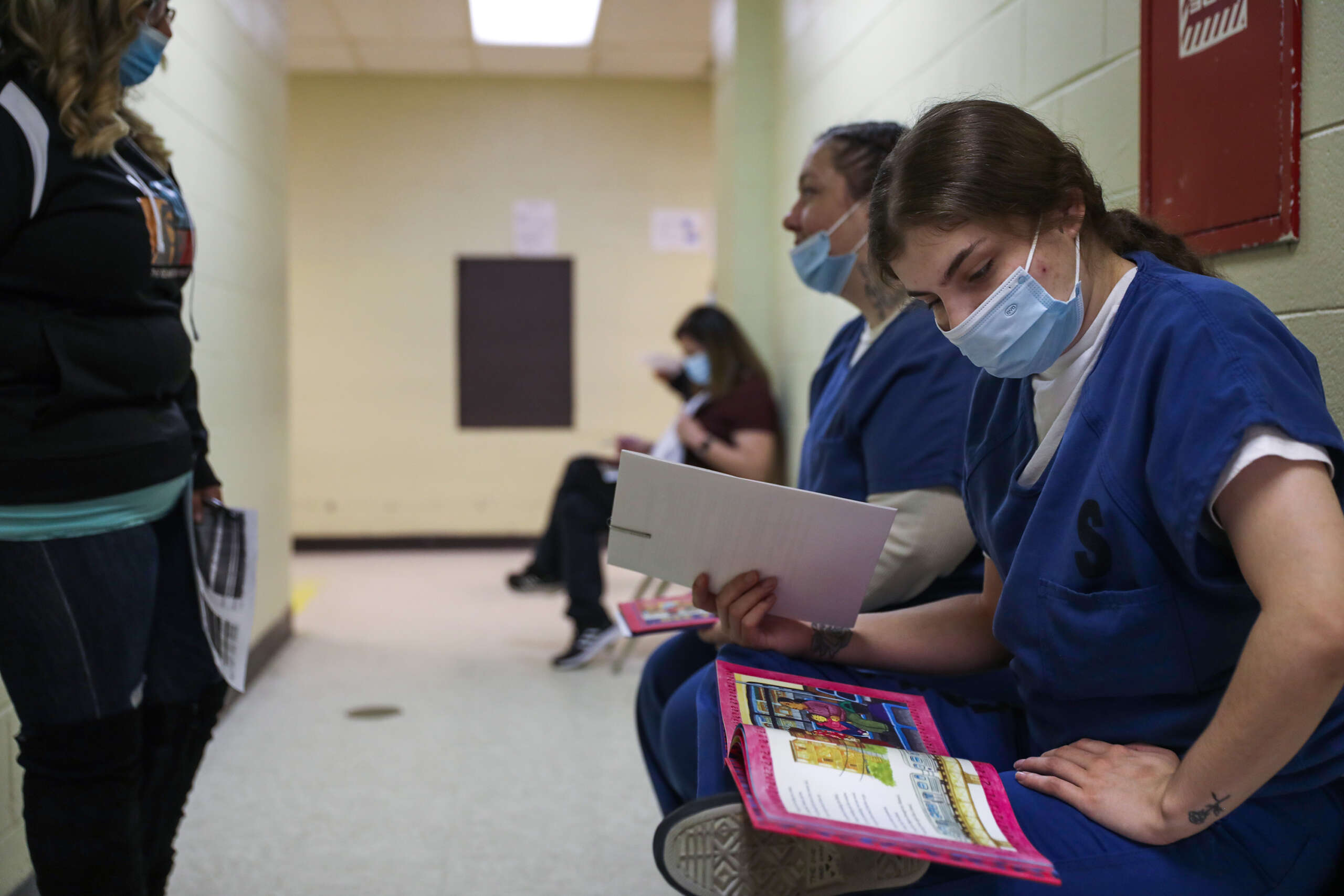

On September 3, Illinois prison officials moved — by emergency rule — to replace most physical mail with scanned copies, though a key legislative panel has already pushed back. At the same time, New York is installing mail scanners in prisons, raising alarms about privacy and attorney-client privilege. Texas has already shifted to “digital mail,” where letters are scanned and delivered on tablets or as photocopies. Though billed as a way to reduce contraband, these “paperless” policies constrict how people read, write, and organize behind prison walls. Protecting incarcerated people’s access to physical mail and inside-led print publishing is a feminist public safety issue. These letters and publications sustain dignity, care, legal literacy, and organizing. This is perhaps most clearly exemplified by The Fire Inside, a physical newsletter written by, for, and about people in women’s prisons that digitized, heavily surveilled systems would otherwise stifle or erase. And as PEN America has documented, prisons now block “staggering numbers” of books and other reading materials for arbitrary reasons, from content to even the color of wrapping paper. In that environment, a physical newsletter written by, for, and about people in women’s prisons is exactly the kind of publication digitized, heavily surveilled systems can stifle or erase. Launched nearly three decades ago by the California Coalition for Women Prisoners (CCWP), The Fire Inside doubles as a living archive and a classroom — where incarcerated women and gender-expansive people teach what resistance, care, and coalition look like across the razor wire. “No One Gets Free Alone,” a core principle of CCWP and prison abolition, isn’t just a slogan — it’s the idea that freedom is collective work: sharing legal know-how, care, and resources through networks that keep people safe. This is why the newsletter matters beyond its pages. The ability to write, read, and share ideas is constantly contested — mail gets delayed, censored, or paywalled — so keeping that flow alive is part of the fight. Civil‑liberties researchers have documented staggering prison book bans and the rapid growth of pay-to-use e-messaging that leave out prisoners who can’t or won’t pay for those messages. Against that tide, The Fire Inside shows what happens when people insist on thinking together anyway. The newsletter offers a prime example of collective analysis and everyday organizing. In one issue, Ellen Richardson describes waking up “every morning fighting a dragon with a teaspoon.” She isn’t being dramatic. She is naming the grind of a place built to exhaust people — denied meds, delayed mail, endless forms. Her excerpt traces what fighting with a “teaspoon” looks like in practice: walking a neighbor through a medical request, sharing a template for a grievance, showing a new arrival how to document harassment so it sticks. None of it reads as grand strategy, but that’s the point. The work is small, steady, and collective. In Ellen’s hands, survival skills become political education — refusing the daily attempts to erase people and building power person-to-person. There is a clear through-line that connect these pages. In the 1990s, Charisse “Happy” Shumate began organizing the way most sustained work starts: by helping women document what was happening to their bodies and what the prison refused to do about it. Inside, women remember her first for how she showed up: warm, smiling, and determined to stand up for people she didn’t even know. As Mary Shields put it, once she met Shumate in the battered women’s group, “she will stand up for you.” When women kept getting turned away from medical or left “laying outside of medical crying, begging for help,” Shumate didn’t just file her own complaints — she taught other women how to write theirs, and she won them. She told people, “We got to get some help… from the outside,” and then she did exactly that, recruiting women inside to work together and bringing in outside advocates to push the Shumate v. Wilson fight on medical neglect. That mix of tenderness and strategy — checking on women who stayed to themselves, helping them name abuse, showing them how to write it up, and connecting it to allies beyond the walls — is the model the newsletter later carried forward. Shumate’s ground-level work grew into coordinated complaints and, eventually, the lawsuit that named medical neglect and demanded standards of care. In her own account in The Fire Inside of taking on that role, Shumate was frank about the cost — retaliation, being labeled a troublemaker — and about why she did it anyway: Leadership from inside was necessary because no one else would make the case with the same precision or urgency. Read alongside the women who organized with her, it’s not a story of solitary heroism but of relay — step-by-step practices copied, taught, and passed person to person despite constant surveillance and risk, so the knowledge wouldn’t be lost. The archive also records how gender policing and homophobia shape punishment in “women’s” facilities, which can otherwise be difficult to identify and report upon. A trans advocate describes a guard’s gendered harassment as “forced feminization,” exposing how institutional power punishes anyone who fails to conform to stereotypes of womanhood. Decades earlier, Shumate called out staff for labeling and targeting queer women. Taken together, these testimonies show how prisons are engines of gendered and sexual violence — evidence that safety cannot be built through cages. In interviews I conducted with longtime contributors, I heard directly about the importance of this writing as a way to organize. Jane Dorotik, who wrote for The Fire Inside during her 19 years at the California Institution for Women (CIW), described writing as a way to humanize a system bent on erasure and to pass along concrete tools. For example, in her 2008 essay “Living on the Inside,” Dorotik spells out everyday survival strategies — from tracking medical requests to sharing grievance templates — showing how first-person writing can become infrastructure for others. Kelly Savage-Rodriguez, a formerly incarcerated organizer with the California Coalition for Women Prisoners, names this practice: “If you’re going to reach one, teach one.” In our interview, she described how that ethic looks day to day: passing scripts for medical requests, sharing grievance checklists, and showing newcomers how to navigate the system so the knowledge keeps moving. Through writing, analysis moves from one person to a unit, across the yard, and into statewide organizing. For example, a run of The Fire Inside columns on medical neglect at CIW didn’t just document harm; writers pooled step-by-step grievance language and contact lists that CCWP turned into coordinated filing campaigns and outside call-in days — moving from one woman’s column to a unit-wide push and then to statewide pressure on health care officials. That pressure helped bring outside attention to the suicide and medical care crisis at CIW and pushed the state to increase monitoring and intervention for women at high risk of self-harm. Likewise, profiles and first-person essays from people serving life without parole fed the #DropLWOP clemency effort. Inside writers mapped the steps for supporting petitions and outside allies amplified them. That infrastructure helped power commutations for several women, including Kelly Savage-Rodriguez, and continues to scaffold statewide organizing. The Fire Inside newsletter shows that abolition feminism isn’t some far-off goal, it’s about helping people survive now while building a better future. It means putting the people most affected at the center, treating care as a strategy — not a side issue — and judging success by whether people’s dignity actually grows. It’s a reminder that if you don’t change who has power, reform can cause new harms. Reforms shaped by incarcerated people, though, can drive real change. At the same time, these mail-scanning and e-messaging policies aren’t neutral. They give prisons and their private vendors two things at once: tighter control over what people can read, write, and keep — which makes it easier to block dissenting or organizing materials — and a new revenue stream through contracts, per-message “stamps,” and paid access to scanned mail. Groups like Prison Policy Initiative and PEN America have warned that digitizing mail often means people pay more for less privacy — their letters are scanned, stored, and sometimes shared, but they still don’t get the original. In other words, this isn’t just about “security.” It’s about suppressing inside-led political education and opening up another profit channel for the prison-industrial complex through technology contracts. Rather than digitizing or restricting communications from within prisons, we should publish the analysis already coming from inside. We need to promote systems that let people learn from each other — like newsletters that circulate across facilities, inside-out education programs, or resource packets that offer step-by-step guides for medical advocacy and legal rights. Libraries, study groups, and correspondence courses make it possible for knowledge to move across years and institutions, building continuity where the system tries to impose isolation. Just as important, resisting censorship means challenging blanket book bans, protecting access to original mail, and auditing mailroom rejections so political writing and community analysis can still get through. As Illinois, New York, and Texas illustrate, these choices are being made right now. Nobody gets free alone — but when we read and organize with the women and gender-expansive people who keep writing across the razor wire, we get closer together.