By Lauren Gravitz

Copyright scientificamerican

This article is part of “Innovations In: Alzheimer’s Disease” an editorially independent special report that was produced with financial support from Eisai.

A diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease is typically followed by years of uncertainty, grief and a painful decline into oblivion. But although there is so much researchers still don’t understand about the disease and what drives it, scientists are making progress faster than ever before and providing patients and their families with options for both diagnosis and treatment.

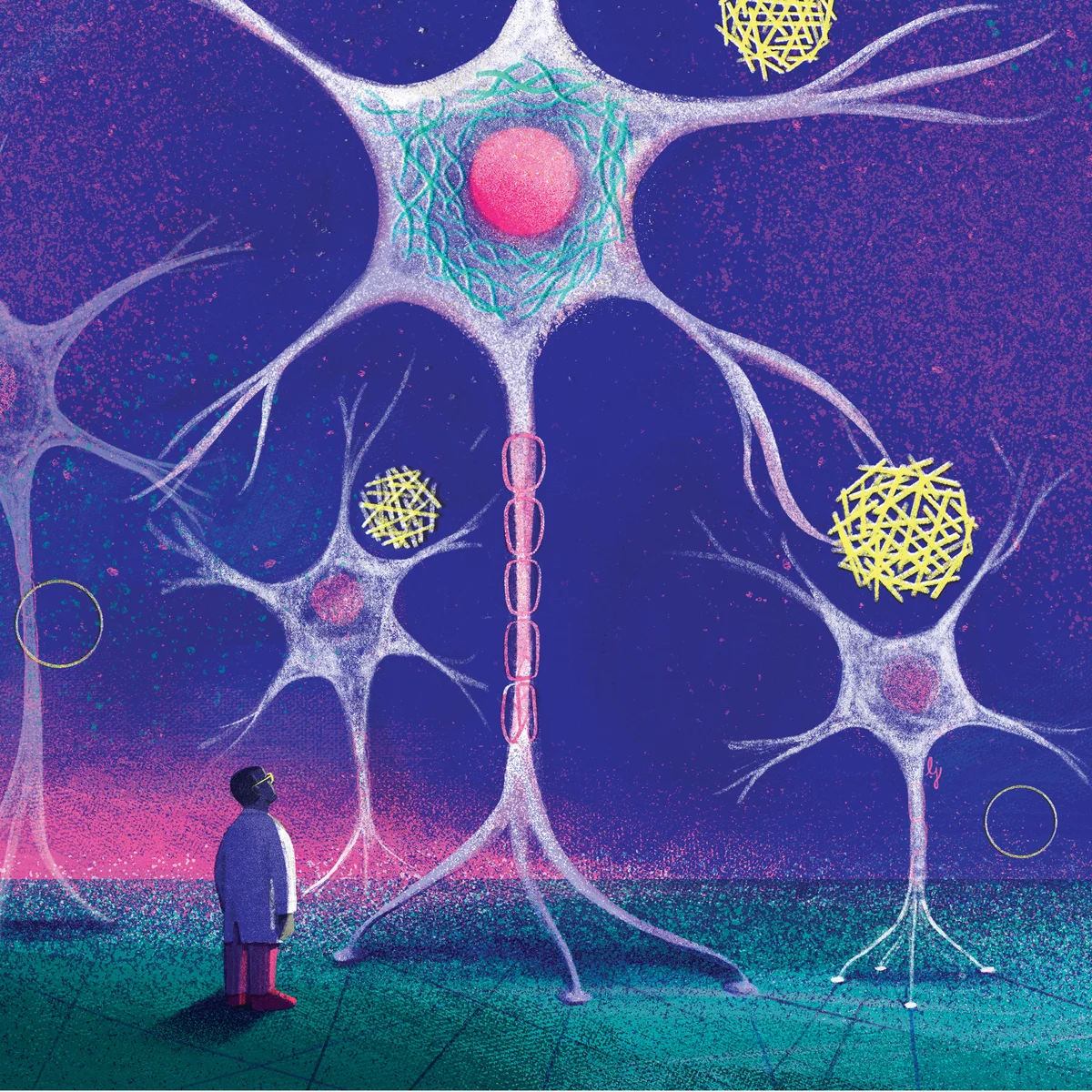

Over the past few decades researchers have begun to realize that Alzheimer’s is more than the tangles of tau proteins and clusters of amyloid plaque that are the defining biological signs of the disease. Today, as Esther Landhuis describes, with the help of detailed graphics, there are more than 100 ongoing trials aimed at slowing or even stopping disease progression, and they target a variety of underlying mechanisms. The first therapies that specifically home in on and break up amyloid plaques have already been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. In clinical trials, they slowed decline for some people with early Alzheimer’s, but, as Liz Seegert reports, the drugs also come with substantial risk and are not a one-size-fits-all solution.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Changes to daily habits, such as increased exercise and social interaction, better nutrition, and supplements, are another option to consider. Sara Harrison notes that although the results from studies are mixed, researchers hope that focusing on someone’s day-to-day health can delay onset of the worst symptoms of dementia. Such improvements aren’t available to everyone, however. Black Americans are twice as likely as white Americans to be diagnosed with Alzheimer’s or other dementias. Jyoti Madhusoodanan analyzes the substantial evidence that this higher rate is a direct result of systemic racism, environmental pollution, and other experiences related to discrimination.

The earlier someone is diagnosed with Alzheimer’s, the sooner they can begin interventions and start to plan for the future. Blood tests can finally make this early detection easier. They’re not infallible, however. Cassandra Willyard explains that the currently available blood tests are less a screening tool and more part of a confirmatory approach, best for people already experiencing dementia symptoms.

The global incidence of Alzheimer’s is increasing at a rapid rate. In the U.S., more people than ever are being diagnosed even as the number of care options dwindles. Tara Haelle explores the reasons for that and profiles one program aiming to help states coordinate and improve care for dementia patients and their caregivers.

Alzheimer’s is a devastating diagnosis. But for the first time since the condition’s initial description in 1906, scientists and clinicians are providing both dementia patients and their family members with glimmers of hope.