Most of the world’s art is locked away and will never be seen. This isn’t due to any nefarious reason, simply the ravages of time — historical paintings are degraded and can require months, years, or even a decade of sluggish, painstaking restoration. As a result, about 70% of paintings in institutional collections are not on public view.

Fortunately, MIT engineer Alex Kachkine has developed a digital art restoration method that revitalizes artworks in a fraction of the time taken by conventional, hand-painting methods.

By using deep-learning methods to create a thin mask that’s applied over a damaged painting, Kachkine hopes to save the countless artworks languishing in dark drawers and lonely backrooms.

Preventing a Painting Pandemic

Public art museums emerged in the 17th century and have since accrued an overwhelming collection of donated works. As paintings pile up, so do the costs of restorations and storage, leaving museums with too few funds, space scarcities, and overworked restorers. As a result, high-pedigree portraits are prioritized while works by lesser-known artists may never meet the adoring gaze of art-lovers.

Even with ample time and attention, it’s a struggle to restore damaged paintings, which may have thousands of minuscule scratches with sizes akin to “a credit card placed on the surface of the Eiffel Tower.”

It’s also extremely challenging to match both the colors and the composition, combining thousands of ever-so-slightly different hues while preserving the artistic intentions of a long-departed painter. So Kachkine developed a digital, AI-powered method to imbue a damaged painting with its former beauty:

Drawing on Childhood Inspiration

Kachkine became enamored with art while on a childhood trip to the McNay Art Museum in San Antonio, Texas. A seascape by famed French Impressionist Pierre-Auguste Renoir captured Kachkine’s attention (and imagination), so he ditched his tour group to better appreciate the museum’s milieu.

Now, Kackhine combines his affinity for art with a generational love of engineering. His parents hold engineering degrees, his grandfather built bridges, and his grandmother designed autopilot systems for Soviet fighter jets.

As his art affinity blossomed, Kachkine started buying more of it: “Many people put their money into savings accounts, and I put money into [artworks],” he says. “As someone with a degree in economics, I should probably know better, but they bring me a lot of joy.”

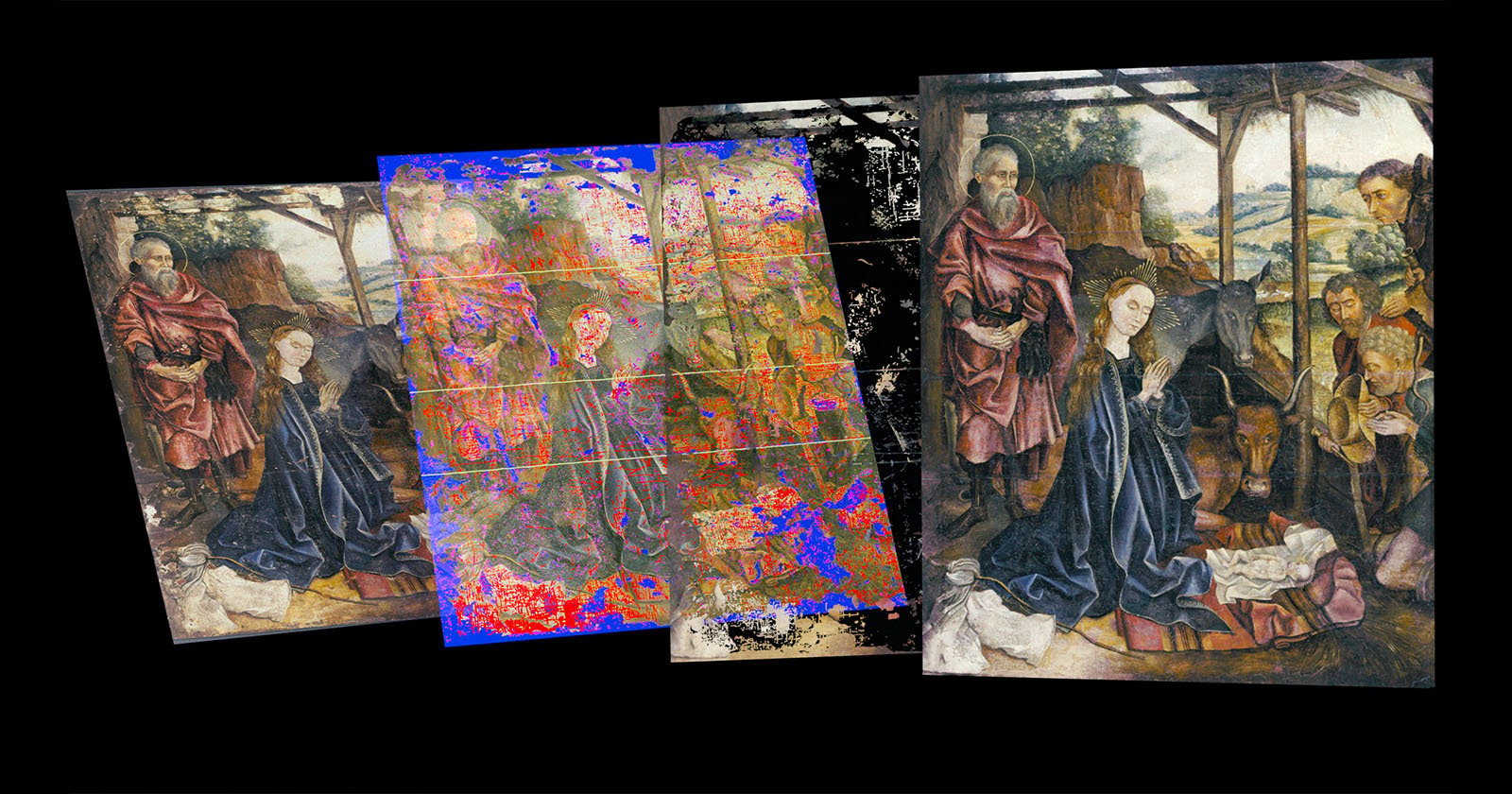

Kachkine used one of his acquired paintings as his artistic guinea pig: a supremely scuffed version of the Adoration of the Shepherds, created by an unknown artist based on an original work by 15th-century painter-engraver Martin Schongauer.

Kachkine’s algorithm-powered restoration method performed an incredible, numerically staggering amount of work: it “automatically identified 5,612 separate regions in need of repair, and filled in these regions using 57,314 different colors.”

Mask On, Mask Off

Kackhine’s method scans a painting for damage and automatically formulates the correct color restorations, translating that digital restoration into a 2D polymer mask that can be physically applied over the original painting.

The mask is made of two distinct, overlapping layers. The first is a layer of colored inks, followed by an identical layer in white ink, which is necessary to recreate a painting’s chromatic nuances.

Equally important, this mask can easily be removed or dissolved, while a digital version is saved to catalog every detail for future restorations.

Expediting Art Restoration

Overall, Kachkine’s digital method is orders of magnitude faster than traditional, hand-painted restoration methods, with the ability to fill in thousands of damaged areas in just a few hours. Kachkine says that restoring a similarly damaged painting would have otherwise taken 9 months of part-time work.

Indeed, in a proof-of-concept demonstration, applying the restoration took just 3 hours and 26 minutes. In comparison, a manual restoration relying on pigments applied by brush would take approximately 232 hours, or nearly 10 consecutive days of wrist-wracking effort.

About the author: Ivan spends most of his time reading and writing about interesting things. An exercise scientist by schooling, Ivan frequently covers science, technology, history, culture, and sometimes writes a little internet comedy.

The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author.