Copyright STAT

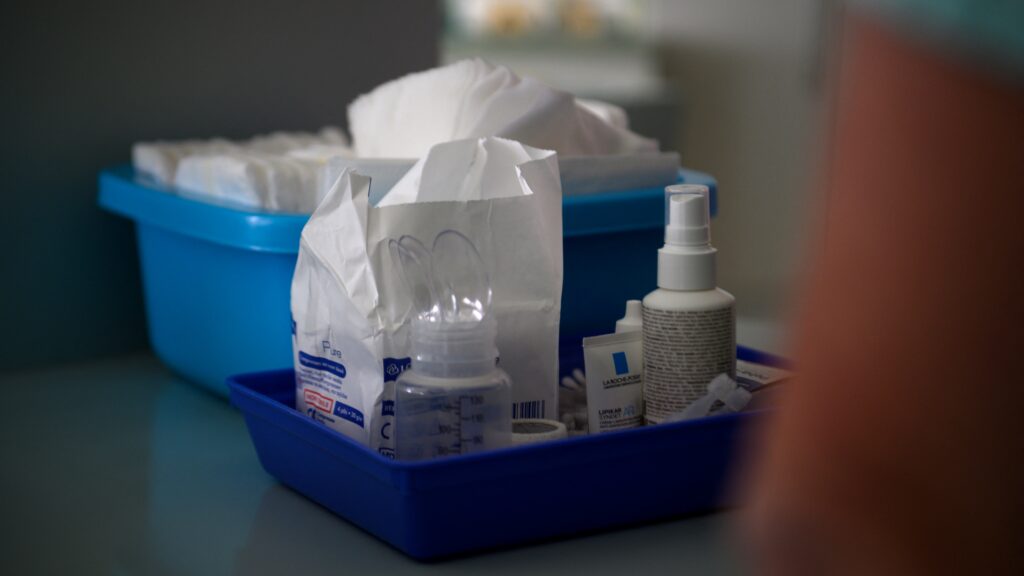

Catheters physically save my life every single day. But my catheters, and with them my health and safety, are now at risk under a new proposal from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services to include urological and ostomy supplies in the competitive bidding program. On Nov. 1, CMS will implement a change that adds urological and ostomy supplies to its Durable Medical Equipment, Prosthetics, Orthotics, and Supplies competitive bidding program. This means that instead of patients and physicians working directly with trusted suppliers to select medically appropriate products, CMS will award contracts to the lowest-bidding companies. Patients will then be restricted to whatever products those winning suppliers choose to offer — regardless of fit, quality, or medical need. Advertisement In practice, this policy strips away patient choice and reduces access to specialized products. That means the catheters my life depends on could be replaced by cheaper alternatives that don’t meet my medical needs. And once the program starts in November, the consequences will be immediate: limited product availability, fewer suppliers, delivery delays, and a higher risk of medical emergencies for millions of Americans. Fifteen years ago, I sustained a complete C6 spinal cord injury in a shallow water diving accident, leaving me paralyzed from the chest down. Since then, I’ve relied on catheters to manage my neurogenic bladder and prevent a cascade of life-threatening complications. These catheters are not optional. They are medically necessary and deeply personal. And yet, for most people, they remain invisible — until disability or aging brings these realities into focus. Early in my injury, I was hospitalized multiple times with sepsis because I was given the wrong kind of catheter. It took years of trial and error — and close coordination with my physician and durable medical equipment supplier — to find the right product for my needs. The catheter I use now has reduced infections and allowed me to live independently, work full time, and travel to speak on national stages to thousands. I cannot go backward. Advertisement I am not just a patient. I’m a global keynote speaker, corporate health equity consultant, full-time advocate, and disability rights leader. I know firsthand the barriers disabled people face within a fragmented, under-resourced health care system. And I know how devastating this policy change could be. Disability doesn’t discriminate. It can happen at any time — to anyone. Catheters are not just for people with spinal cord injuries. They’re for people with bladder cancer, multiple sclerosis, spina bifida, and many other conditions. Their use is widespread, yet they remain stigmatized and poorly understood. We have to change that, especially now. If my bladder becomes overfull and I’m unable to drain it, I can go into a medical emergency known as autonomic dysreflexia. It’s a condition that causes my blood pressure to spike dangerously high, putting me at immediate risk of stroke or death. This is not hypothetical. It’s daily reality. And for me, having the right catheter — correctly sized, properly coated, and made of safe materials — is a matter of life and death. CMS claims this move will cut costs and reduce fraud. But in practice, competitive bidding means reduced patient choice, jeopardized supply chains, and an incentive to push cheap, poorly made products that cause infections, sepsis, and lifelong health consequences. I’ve seen it happen. I’ve buried friends who died from infections caused by inadequate or inappropriate catheter use. If CMS enacts this policy, patients like me may be forced to accept lower-cost alternatives that don’t fit, don’t function properly, or actively put our health at risk. We’ve seen the results of competitive bidding before through delivery delays, poor substitutions, limited supplier access, and massive disruptions to care. In many cases, those short-term “savings” lead to higher emergency room visits, hospitalizations, and long-term costs to the health care system. Former Surgeon General Richard Carmona recently wrote, “While I was surgeon general, the Department of Health and Human Services oversaw a pilot project in Polk County, Florida, in the early 2000s in which CMS included urological supplies in the bidding program. The result? A dramatic reduction in supplier participation, shrinking product availability and real harm to patient care. The data was clear enough that in 2003, Congress specifically carved these products out of future competitive bidding entirely.” Advertisement CMS has justified this move, in part, by citing a recent high-profile fraud case. In June, the Department of Justice announced Operation Gold Rush, which uncovered more than $10.6 billion in fraudulent Medicare claims — many involving urinary catheters. The scale of the fraud was staggering. It involved more than a million stolen identities and products that were never delivered. But let’s be clear: That fraud wasn’t committed by legitimate suppliers or medical professionals. It was orchestrated by criminals exploiting systemic weaknesses like poor oversight and lax identity verification. Competitive bidding won’t stop them — it will only punish patients. At the same time, this proposal threatens suppliers who do things the right way. My provider has helped me access advanced catheter technology — products with hydrophilic coatings that reduce friction and lower the risk of infection. These innovations are possible because of research, investment, and appropriate reimbursement. Slash the rates, and innovation disappears. Personalized care disappears. And people get hurt. As a patient, advocate, and professional, I shouldn’t have to fight this hard for access to supplies that keep me alive. None of us should. There are smarter ways to address fraud and reduce waste without harming patients. Ali Ingersoll is a global keynote speaker, author, corporate consultant, former Ms. Wheelchair America, and fierce health equity advocate.