Frank Farrow dreams of the day when his job no longer exists.

He’s spent more than three years as the executive director of Boston’s Office of Black Male Advancement, a city agency dedicated to ensuring that Black men and boys have the tools they need to succeed and thrive.

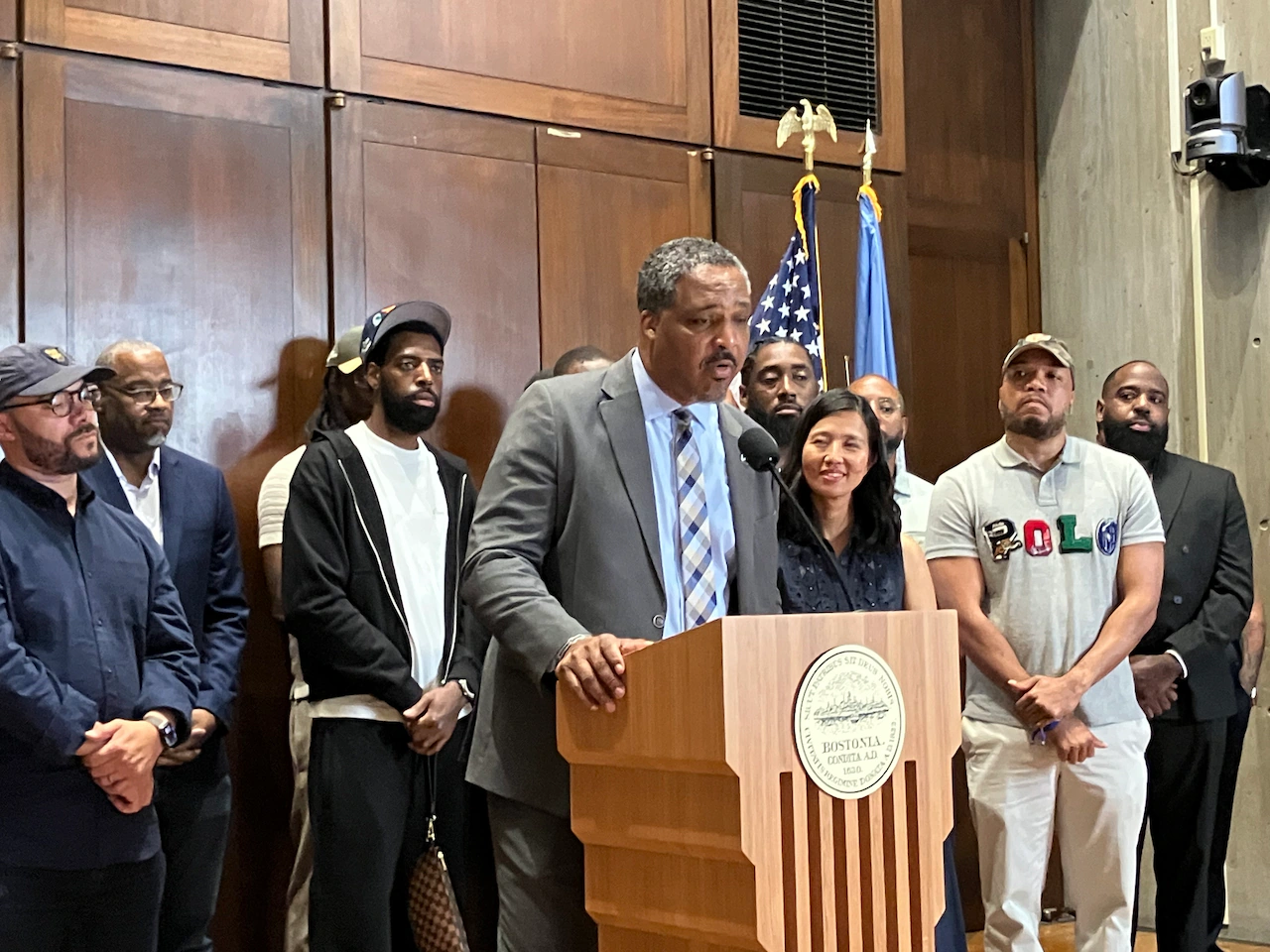

On Monday, the city took another step toward that goal as Mayor Michelle Wu appointed the newest members of Boston’s Black Men and Boys Commission, a 21-member panel charged with advising Wu and her lieutenants on the issues key to a community whose life expectancy is shorter and whose academic and financial achievement lags that of white men.

“Our ultimate goal is to make sure that the Office of Black Male Advancement doesn’t need to exist; to make sure whether it’s housing, education [or] economic opportunity, that Black men and boys have the opportunity to thrive, succeed, to live, flourish and be contributing members of our community,” Farrow said during a news conference at City Hall.

“Boston is better when everyone that looks like us, that lives in this city, is supported and they’re able to then pass [it] back for generations to come,” he said.

During Monday’s brief ceremony in a conference room in her offices at City Hall, Wu said she sees the commission as “critical in our work to make Boston a home for everyone.”

To further that work, Farrow’s office and the commission recently launched the city’s first Equity Study for Black men and boys. It’s aimed at detailing, quantifying and evaluating “the prevalence, significance and scope of inequities impacting Black men and boys in the city,” Wu’s office said in a statement.

The first phase of that study, led by the Boston-based Tury Research Institute, includes an “equity survey” focused on identifying the most pressing issues and challenges facing Black men and boys in the city.

The survey is open to Black men and boys who live in the city and responses can be submitted until Oct. 31.

If some recent data is any indication, from the economy to educational achievement, there’s plenty of ground to make up.

Nearly half of all Black men in Massachusetts who work full-time earn less than $50,000 a year, compared to 30% of all men, according to a study by Boston Indicators, the research arm of The Boston Foundation.

The disparities also grow at either end of the income ladder: While 24% of all men earn more than $125,000, only 9% of Black men reach that same threshold, and 15% earn more than $100,000.

All told, Boston’s Black residents accounted for 19.1% of the city’s residents, according to 2020 U.S. Census data.

Read More: Overdose deaths of Black Bostonians dropped significantly in 2024. Here’s why

Black men also “are disproportionately represented at the lower end of the income distribution, even in a state known for its high wages,” the study’s authors found.

“Black men face many of the same challenges as other men. And they are compounded by longstanding systemic racism and prejudice that continue to limit access to education, employment and opportunity,” the study’s authors concluded.

And when you look at educational attainment over the long haul, Black men have made strides, with more Black men getting bachelor’s degrees between 2000 and 2023, the study showed.

Despite those gains, graduation rates still trail men of all races, and Black women, the research found.

And “the consequences of these educational gaps can be far-reaching, translating into limited career opportunities, suppressed earnings potential, and workforce inequities,” the study’s authors wrote. “And even with a college degree, Black men are more likely to face unemployment and earn less than their peers with similar credentials.”

Former Boston City Councilor Tito Jackson, the commission’s chairperson emeritus, said that he wants to “flip the script” on that data.

“So often, we speak about Black men in deficit language and deficit terms,” Jackson said. “No more. This is about possibilities. It’s about where we’re going, and, frankly, where the city can’t go without us.”

“As goes Black men, goes the city of Boston,” he said, adding “as someone who just turned 50, Black men in the city of Boston deserve to grow old in the city of Boston.”

“… Frankly, we deserve to be alive in our city that has a 33-year disparity between Back Bay and Roxbury,” Jackson continued. “And so the work that we do [for] the new group of individuals who are bigger, badder and better is so urgent and it is so timely. And as I said earlier, we need the best leaders in the most difficult times. And I know that you brothers who are receiving this baton are going to be able to continue this work.”

Maddrey Good, the executive director of the New England Culinary Arts Institute, is one of the people picking up that baton. He’s the commission’s newest chairperson.

“I come to you a child of Boston, but most importantly, a child of Roxbury,” Goode said, referring to the neighborhood that’s the beating heart of Black Boston.

“And I’m just really looking forward to working with the new commissioners. And I’m even more excited about the young Black men, [the] young Black boys who will be the future commissioners,” he said, to the audience’s vocal approval.

Looking back on his own upbringing, Goode said he knew he was “[standing] on the shoulders of giants.”

“But now,” he said. “We all get to create more giants.”