By Wynna Wong

Copyright scmp

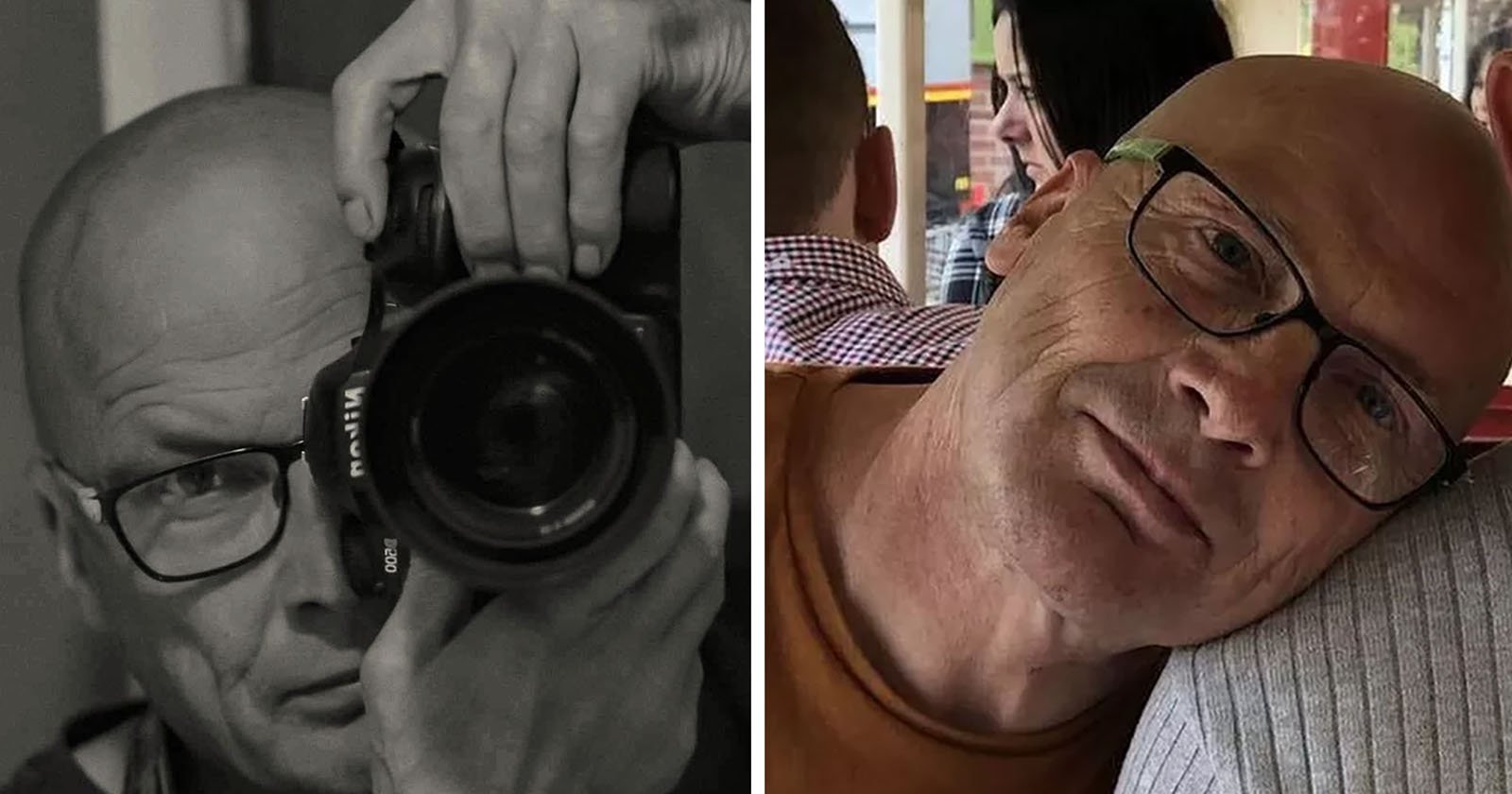

Hongkonger Wilson Tsang Wai-shun began following basketball in secondary school, a time when the National Basketball Association (NBA) experienced one of its fastest expansions, acquiring both fortune and fame with fans.

While much of that was down to the likes of global superstar Michael Jordan, in China, the sport had by then been popular for decades.

But then NBA commissioner David Stern’s initial 1987-88 agreement to broadcast games on China Central Television, around the time Jordan was transcending the game, turned the American league into a major player in the country’s sporting landscape.

“The emergence of Jordan, and around the same time, this Japanese manga called Slam Dunk became popular … all these contributed to why a lot of people in Hong Kong got into basketball,” Tsang, who is now in his 40s, said.

It remains an integral part of his life, and the sales manager is one of several administrators of “Slamtalk”, a Hong Kong-based online forum with 46,300 members.

“Basketball is indispensable for many people … as adults, the meaning is to maintain friendships and watch the games together,” he said.

For Bobby Chan, a 30-year-old designer who runs the Instagram page lakers_hkfansclub with 33,500 followers, the love for basketball began in primary school.

“I would try to find ways to watch the games on the computer during recess,” he said, adding that it was the death of Los Angeles Lakers star Kobe Bryant in 2019 that inspired him to start the account.

“It was a way for me to mourn him with others,” he said. “It eventually turned into a basketball news page of sorts and I would share news or thoughts every few days.”

Chan, and England-based Tsang, are just two of the tens of thousands of Hong Kong fans, with millions more in mainland China.

The Slamtalk team will be in Macau next Friday for the pre-season friendly between the Brooklyn Nets and the Phoenix Suns.

That will be the first NBA game in China since Daryl Morey’s ill-advised tweet in 2019 that led to the league being scrubbed from all social media, dropped from CCTV, and abandoned by numerous businesses and companies.

Basketball’s enduring popularity

Declared a national pastime, alongside ping pong, after a public vote in 1935, basketball was given a prominent place when Zhou Enlai, China’s first premier, endorsed the game for its contribution to fitness and promotion of teamwork.

It exploded in the country’s consciousness with the introduction of free-to-air matches in the early 1990s, the arrival of superstars such as Jordan and the professionalisation of the Chinese Basketball Association (CBA) in 1995.

In 2010, the NBA rode on the momentum to open its official Weibo account. By 2017, it had more than 33 million followers, six million more than on Twitter at the time.

Two years later, it was one of the most popular sports leagues in the country, with its business operations, encompassing media rights, licensing, and sponsorships, valued by Forbes then at around US$4 billion.

At the time, NBA deputy commissioner Mark Tatum told Reuters an estimated 300 million people actively played or followed basketball in the country.

“A lot of it is the simplicity of the game,” said Mark Dreyer, founder and editor of China Sports Insider based in Beijing, and author of the book Sporting Superpower: An Insider’s View on China’s Quest to Be the Best.

“For basketball, you don’t really even need a court, you just need a hoop to play at some level.”

He added the NBA as a league was dominant in its sport, as there were “no competitors whatsoever”.

“The CBA is miles below and there are European leagues, but they just don’t have a global presence in the same way, so the NBA is the only thing in that space,” he said.

Jay Li Jintian, former head of strategic development at the CBA, added: “I believe it’s a fact that basketball is the most ‘social’ sport on school campuses across China.”

Li told the Post the sport had a unique combination of “collectivism and individualism”, making it highly appealing and socially relevant within Chinese society, and also required minimal equipment and space – ideal for crowded urban environments.

The arrival of Yao Ming

When the 2.29 metre-tall (7.5 foot) centre Yao Ming was drafted first overall by the Houston Rockets in 2002, he instantly became a national hero and a cultural icon who, like Jordan, transcended the sport.

“Fans will always see the NBA as the ultimate place where a Chinese player can prove his true worthiness internationally,” Li said.

In 2019, the NBA’s digital media deal with Tencent alone was valued at US$1.5 billion over five years, with the Chinese media outlet estimating about 500 million Chinese people were consuming NBA content.

The league and its partner brands invested heavily in the country with grass roots programmes such as the NBA Academy and the Junior NBA programme, player tours and digital content designed to engage a rapidly growing middle class.

“The enormous fan base in China makes it impossible for the league to ignore,” said Thomas Oates, American studies and mass communication professor at the University of Iowa, who has studied Yao’s career and its dual function for the league, simultaneously promoting the NBA to America and China.

“The fact that the league felt the need to apologise immediately after Daryl Morey’s tweet criticising Chinese policy in Hong Kong shows that they understood the importance of the market even then.”

A sudden blackout

Morey, the then-general manager of the Houston Rockets, brought the relationship to a crashing halt in October 2019, when he tweeted “Fight for Freedom. Stand with Hong Kong” during the height of anti-government protests in the city.

It brought an immediate and devastating response from the Chinese government, with CCTV and Tencent suspending all NBA content, while corporate sponsors pulled millions of dollars in deals.

“If you’re Tencent, you’ve got a massive investment in protecting your rights, but there was nothing they could’ve done, because for something like this, when it becomes so political, then it was CCTV who were the ones to make the call that it couldn’t be broadcast,” Dreyer said.

The Lakers and Nets were playing pre-season games in Shanghai and Shenzhen when Morey sent out a tweet that Adam Silver, who is now NBA commissioner, estimated in 2020 had cost the league US$400 million in the first year alone.

While the NBA called the quickly deleted tweet “regrettable”, Silver defended Morey’s right to “freedom of expression”. Morey later apologised, saying he did not intend to cause offence to “our friends in China”.

“One of the biggest mistakes [the NBA] made was putting out separate statements in English and Chinese,” Dreyer said.

“And you could tell that different teams were involved in this – the US statement was very much scripted for a US audience, and the NBA China one was not a perfect translation, and people were picking these apart … and this would basically backfire in both markets.”

On returning home, Lakers star LeBron James told reporters Morey “wasn’t educated on the situation at hand … and so many people could have been harmed, not only financially, but physically, emotionally, spiritually”.

Nets owner Joe Tsai, meanwhile, penned an open letter outlining the historical context for why fans, like the rest of China’s 1.4 billion citizens, viewed territorial integrity and sovereignty as “non-negotiable” issues.

“The hurt that this incident has caused will take a long time to repair,” Tsai wrote on his Facebook page. “I hope to help the league to move on from this incident. I will continue to be an outspoken NBA Governor on issues that are important to China. I ask that our Chinese fans keep the faith in what the NBA and basketball can do to unite people from all over the world.”

Political analyst Wilson Chan Wai-shun, co-founder of Pagoda Institute in Hong Kong, said Beijing’s reaction at the time was expected, as the protests touched upon national security, while the NBA was seen as a foreign entity.

“It was a very sensitive time, especially as Beijing felt the movement at the time, whether directly or indirectly, had some foreign forces trying to interfere,” he said.

“So any foreigner, even if well-intentioned or truly just wanting to speak their own mind on social media, would have been viewed by Beijing as supporting the protests.”

On the difference between the Chinese and English statements, Chan added while it was not uncommon for multinational companies to conduct “localised public relations strategies”, the high scrutiny over the incident led to public perception that the league was sacrificing Western values to maintain access to the Chinese market.

A deeper meaning

However, the event was not simply seen as a spontaneous consumer backlash.

Assistant Professor Gloria Xiong of Colby College, an academic studying economic statecraft, said the episode was widely viewed as a systemic signal from Beijing.

“The 2019 NBA boycott is best understood as part of a wider set of episodes where foreign [multinational corporations] faced political pressures from China,” she said.

“China’s informal approach to economic statecraft often results in a less transparent and longer process for lifting punitive restrictions,” she added.

While commercial success in China can often be linked to political concerns, Chinese fans are also now far more sensitive to anything that hurts the country’s image, and have readily leapt to its defence themselves in recent times.

For the Chinese fan base, that period of disruption created a conflict between national loyalty and desire to continue enjoying the sport.

“Sports fans often find different ways to negotiate their identity with the team during the crisis,” Professor Oliver Pu Haozhou of the University of Dayton, an expert on fan psychology, said.

“Some managed the cognitive dissonance by attributing the controversy to specific individuals [such as Morey] rather than the team or league, or by distancing the team from the political issues.

“More importantly, the NBA never considered withdrawing from the Chinese market and has continued operating there throughout the crisis, albeit in a more low-key manner.”

Tencent reestablished NBA content in the form of limited highlight reels and archival footage weeks after the incident, while individual players such as Stephen Curry, James Harden and Kyle Anderson maintained strong engagement with fans on Chinese social media platforms like Weibo, Douyin and RedNote.

Victor Wembanyama, one of the league’s most promising young players standing at a towering 2.24 metres, spent 10 days at a Shaolin Temple in Henan province while recovering from an injury.

E-commerce and merchandising activity remained in business on mainland platforms in the months and years after the Morey fallout.

A strategic return

Six years after the blackout, the NBA announced in December that it was officially returning to China with the Nets and Suns playing in a multi-year deal with Sands China that sources told the Post was worth more than US$10 million.

Pu described the event as an “ice-breaking trip to resume and normalise the relationship,” and noted that holding the event in Macau, a special administrative region with a lower political profile and direct financial incentives, was a strategic choice.

“It could also be a ‘trial run’ to gauge reactions from both government and fans and provide guidance for future steps before re-entry into mainland cities,” Pu said.

Ultimately, he believed the league’s “patient” approach had helped preserve the Chinese market, but it was now fully aware of the need to find a constant “balance between its commercial interests and political risks”.

Former CBA executive Li added it was difficult for other basketball associations, even the Chinese league, to replace the NBA, as they served “fundamentally different purposes”.

“I think the best basketball talent from all over the world should always aim to make it to the NBA one day if they can dominate in their domestic leagues,” Li said. “Fans can always easily follow both the NBA and the domestic leagues where they are from.”

Where Hong Kong misses out

Allan Zeman, chairman of the Lan Kwai Fong Group and an independent non-executive director of Wynn Macau, said the city had unique advantages and motivations in attracting such an event.

He noted its government-mandated goal to have the non-gaming sector contribute 60 per cent of gross domestic product (GDP) by 2028, which was a component of its 2022 licence renewal process for its six casino operators.

“It’s brought a lot of people to Macau, not just for gambling, but for really having a good time. And it’s been worked out very, very well,” he said.

“Choosing Macau over Hong Kong, I guess for one, Macau is doing a lot of events now because that’s part of the deal for every casino that’s assigned the licence for continuing.”

He added casino operators had the resources and willingness to “pay crazy money” for the NBA games to cover substantial costs for the two teams, while Macau also has an NBA-standard venue to host matches, unlike Hong Kong.

Zeman noted that while Macau hotels had been operating at high occupancy this year, the NBA games “definitely helped with having the games for the weekend”, drawing young people and driving visitor numbers.

Hong Kong and Macau have chosen different approaches to attracting globally important events. While Hong Kong does not have the casino business, it can now boast of Kai Tak Stadium and is able to stage entertainment and sport on a grander scale.

“We do have different grants and different schemes by the government, if you want to bring a star out or something like that. But I imagine it is a lot of money to bring out these many players,” he said.

The fans, at least, are seeing the return as a simple joy and celebration of sport.

As Oliver So, another Slamtalk administrator who will be going to the Macau NBA games, puts it: “I’m truly happy about the return of the China games.

“Compared with past locations, Macau has a highly developed tourism industry and is more conveniently located for Hong Kong residents.

“For fans, it’s a blessing for us to have this rare opportunity to experience NBA-level basketball.”