Copyright bbc

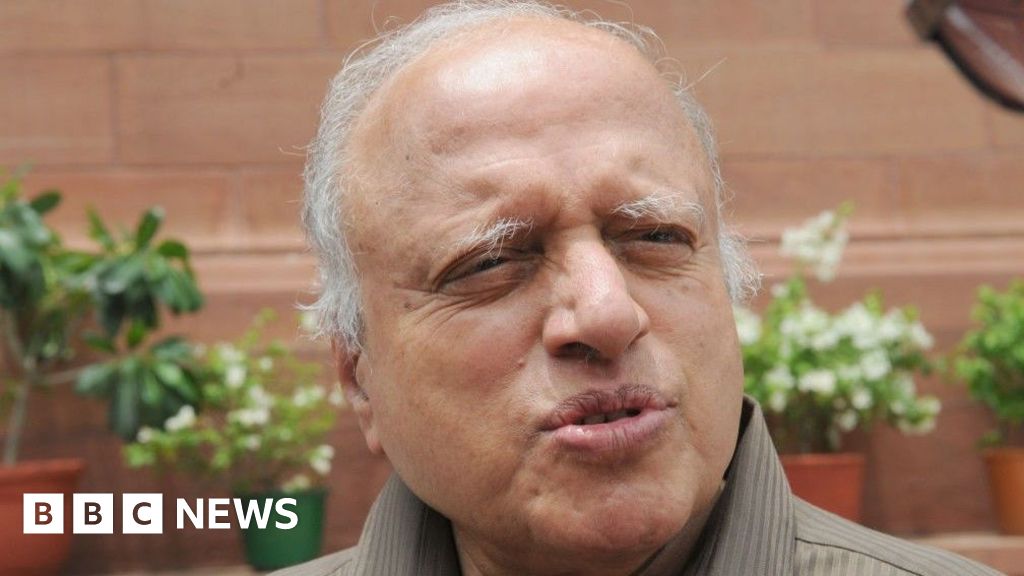

In 1963, Swaminathan persuaded Borlaug to send Mexican wheat strains to India. Three years later, as part of a nationwide experiment, India imported 18,000 tonnes of these seeds. Swaminathan adapted and multiplied them under Indian conditions, producing golden-hued varieties that yielded two to three times more than local wheat while resisting disease and pests. The seed import and rollout was far from smooth, Jayakumar writes. Bureaucrats feared dependence on foreign germplasm, logistics slowed down shipping and customs, and farmers clung to tall, familiar varieties. Swaminathan overcame these challenges with data and advocacy - and by personally walking the fields with his family, offering seeds directly to farmers. In Punjab, he even enlisted prisoners to stitch seed packets for rapid distribution during sowing season. While the Mexican short-grain wheat was red, Swaminathan ensured the hybrid varieties were golden to suit leavened Indian breads like naans and rotis. Named Kalyan Sona and Sonalika - "sona" means gold in Hindi - these high-yielding grains helped turn the northern states of Punjab and Haryana into breadbaskets. With Swaminathan's experiments, India quickly shifted to self-sufficiency. By 1971, yields had doubled, turning famine into surplus in just four years - a miracle that saved a generation. Swaminathan's guiding philosophy was "farmer-first", according to Jayakumar. "Do you know the field is also a laboratory? And that farmers are actual scientists? They know far more than even I do," he told his biographer. Scientists, he insisted, must listen before prescribing solutions. He spent weekends in villages, asking about soil moisture, seed prices, and pests. In Odisha, he worked with tribal women to improve rice varieties. In the dry belts of Tamil Nadu, he promoted salt-tolerant crops. And in Punjab, he told sceptical landowners that science alone wouldn't end hunger and that "science must walk with compassion". Swaminathan was keenly aware of the challenges facing Indian farming. As chair of the National Commission on Farmers, he oversaw five reports between 2004 and 2006, culminating in a final report that examined the roots of farmer distress and rising suicides, calling for a comprehensive national farmers' policy. Even in his late 90s, he stood with farmers - at 98, he publicly supported those protesting in Punjab and Haryana against controversial agricultural reforms. Swaminathan's influence extended far beyond India. As the first Indian Director-General of the IRRI in the Philippines in the 1980s, he spread high-yield rice across Southeast Asia, boosting production in Indonesia, Vietnam, and the Philippines. From Malaysia to Iran, Egypt to Tanzania, he advised governments, helped rebuild Cambodia's rice gene bank, trained North Korean women farmers, aided African agronomists during the Ethiopian drought, and mentored generations across Asia - his work also shaped China's hybrid-rice programme and sparked Africa's Green Revolution.