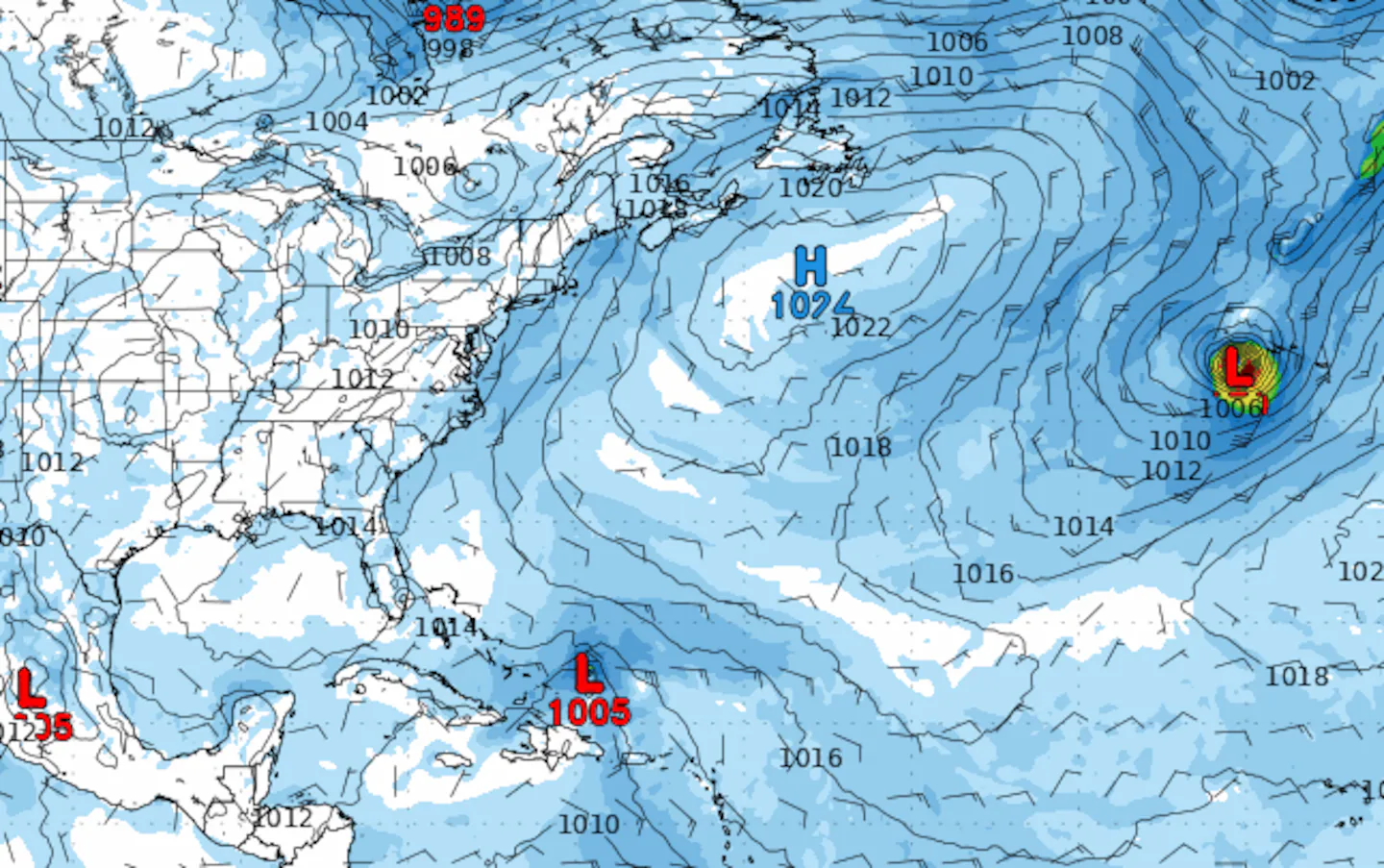

The National Hurricane Center is giving the disturbance to the east an 80 percent chance of developing within the week, while the other one has a 50 percent chance.

These two tropical waves are riding along the southern periphery of the Bermuda High near the Main Development Region (MDR), with a general steering pattern to the west-northwest. Conditions across this part of the Tropical Atlantic have slowly turned more favorable to sustain storm activity over the last week or so, after quite a stretch of dry, stable air kept the tropics quiet.

The ocean waters of the Tropical Atlantic are teeming with well-above-average sea surface temperatures. This holds the potential for rapid development, as we saw with Gabrielle. The ocean needs to be 80 degrees or warmer to sustain tropical development, and temperatures in the Western Tropical Atlantic right now range from 84 to 89 degrees — that’s a lot of storm fuel.

But first, they will need to overcome the pockets of Saharan dust and generally sinking air, which both suppress storm development. It was the same environment Gabrielle had to struggle through. It remains to be seen if the hot seas are enough to help the thunderstorms within these systems overcome any atmospheric challenges. Should the western disturbance, closer to the Bahamas, survive, then the United States may be facing a landfall threat.

And again, this disturbance would have to overcome a tough start, but if it does, there is a good chance that the Northeast could see a hurricane make a very close pass. It is still too early, but the GFS is suggesting that the remnants of Gabrielle may tow the Bermuda High to the east, decreasing the recurve influence on that western storm and instead push it up the Eastern Seaboard.

This is just one model run compared to many, as there is still much to unfold. But it is certainly eyebrow-raising. It’ll ultimately come down to Gabrielle’s remnants and the steering pattern of the winds coming off the United States to see if this potential storm comes close to landfall.

The “X” in the map below marks the location of the tropical waves and their large red and orange areas of potential development.

When and if these systems do emerge as our next tropical storms, the next names on the list would be Humberto and Imelda.

The Atlantic has become much more active after an extensive lull in hurricane activity in which no storms developed in the Atlantic basin from Aug. 28 through the peak of the season, Sept. 10 — a first since 1939! That’s pretty remarkable.