Copyright Kalispell Inter Lake

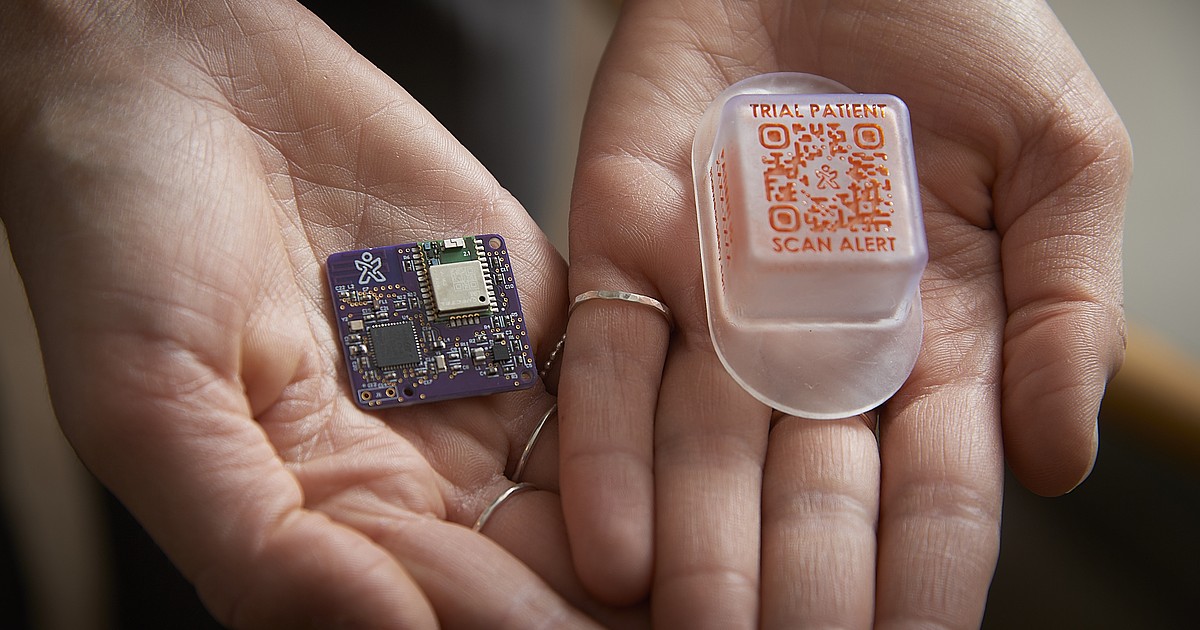

BOZEMAN — A new medical device developed by Montana State University researchers is demonstrating how interdisciplinary innovation can improve health care outcomes in Montana and beyond. TrialWear was invented by Elizabeth Johnson, an assistant professor in MSU’s Mark and Robyn Jones College of Nursing. The device is a wearable electronic patch with a scannable code that links to key information about clinical trial patients’ safety needs when accessing care away from their research site, such as at a local emergency department. It prompts patients with a text message when they enter a medical facility to show the code to health care providers. Broadly, TrialWear seeks to increase the number of clinical trial participants by removing communication barriers between researchers and hospitals, which may result in participants being taken off lifesaving trials if local care decisions are against trial rules. Most often, patients at large, urban hospitals are tapped for clinical trials due to a lack of coordination with rural areas, Johnson said. “Without clinical trial participants, we cannot get new drugs to bedside,” Johnson said. “When surveyed, most people here in the U.S. are willing to go on a clinical trial. But only a small fraction may get to be on a clinical trial due to lack of access or safety issues. We’re looking to narrow that gap.” Sometimes, participating in a clinical trial can provide access to a life-saving new drug or treatment for patients whose previous treatments have failed, Johnson said. But if a provider accidentally gives a patient a medication that could interact with the clinical trial, they may be dropped from it. Historically, clinical trial patients have carried paper cards with information that are easy to lose, Johnson said. But TrialWear carries that information electronically by linking to a database that contains information about patient medications, guidelines and restrictions of the clinical trial. It was inspired by similar technology used to track aid as refugees move from place to place. After several years of testing the device prototypes based on feedback from more than 300 patients, researchers finalized the prototype in July. With the help of MSU’s Technology Transfer Office, it will soon be commercialized, Johnson said. That means Johnson’s team will send the device to hospitals who will provide it to clinical trial patients. Bozeman’s A&E Design is designing packaging for the device. The project has received pockets of money from several funders, including the National Science Foundation, the National Institutes of Health, the American Nurses Association, an MSU Venture grant, and the U.S. Economic Development Administration. Most recently, the team submitted a grant for $5 million from the National Cancer Institute to broaden partnerships with major academic medical centers. Current funding, including from Rocky Mountain REACH, has permitted new partnerships across Montana and Alaska for older adults and youth ages six to 22 to test the final prototype. At MSU, Johnson has collaborated with Geospatial Core Facility researchers Eric Sproles and Erich Schreier; graduate electrical engineering student Noah Hedding; lead mechanical engineer and former graduate engineering student Lea Mulnar; data scientist and former graduate engineering student Jiahui Ma; and community engagement lead former business student Bri Daniels. Additionally, the device’s final form and components have been refined by specialists at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. In 2022, the original TrialWear was a bracelet that patients wore on their wrist. To test its effectiveness, researchers placed the bracelet on a mock patient and then tracked the eye movements of nurses at Billings Clinic working with those patients, which led to an important lesson. “When we looked at the eye tracking data, the overwhelming majority of nurses were looking at the patient’s chest the entire time — which makes complete sense. They were looking for vital signs and signs of distress,” Johnson said. “So then we pivoted to make it a smart patch on the chest.” The moment the design switched from a bracelet to a chest patch, everything changed, Johnson said. The first design was a bulky, 3-inch bracelet with a USB to plug into a computer, which eventually evolved into a lightweight, waterproof patch the size of a quarter. At its heart, TrialWear is a collaborative effort across academic disciplines, Johnson said, adding that she tapped MSU’s Geospatial Core Facility to build the geographic components of the device. Sproles, director of the Geospatial Core Facility, said his team essentially reverse-engineered the software used for package tracking and delivery. The goal was to build technology that delivered an alert when a patient went into any medical facility within a geographic area to ensure communication between clinicians and researchers. Sproles said this project is the first collaboration between the Geospatial Core Facility and the nursing college. “In terms of addressing and improving rural health care, there’s definitely a geospatial component to it that’s quite powerful,” he said. “I feel incredibly honored to be a part of this work.” Sproles said the final TrialWear version leverages a lot of different technologies, and the product would not have been achievable even five years ago due to advancements in 3D printing and satellites. “This effort really speaks to the value of collaboration and innovation, and how getting motivated people together can lead to a great outcome,” Sproles said. “That’s something MSU really excels at, is connecting people with different types of expertise to solve real-world problems.”