By Sumiya Chuluunbaatar

Copyright thediplomat

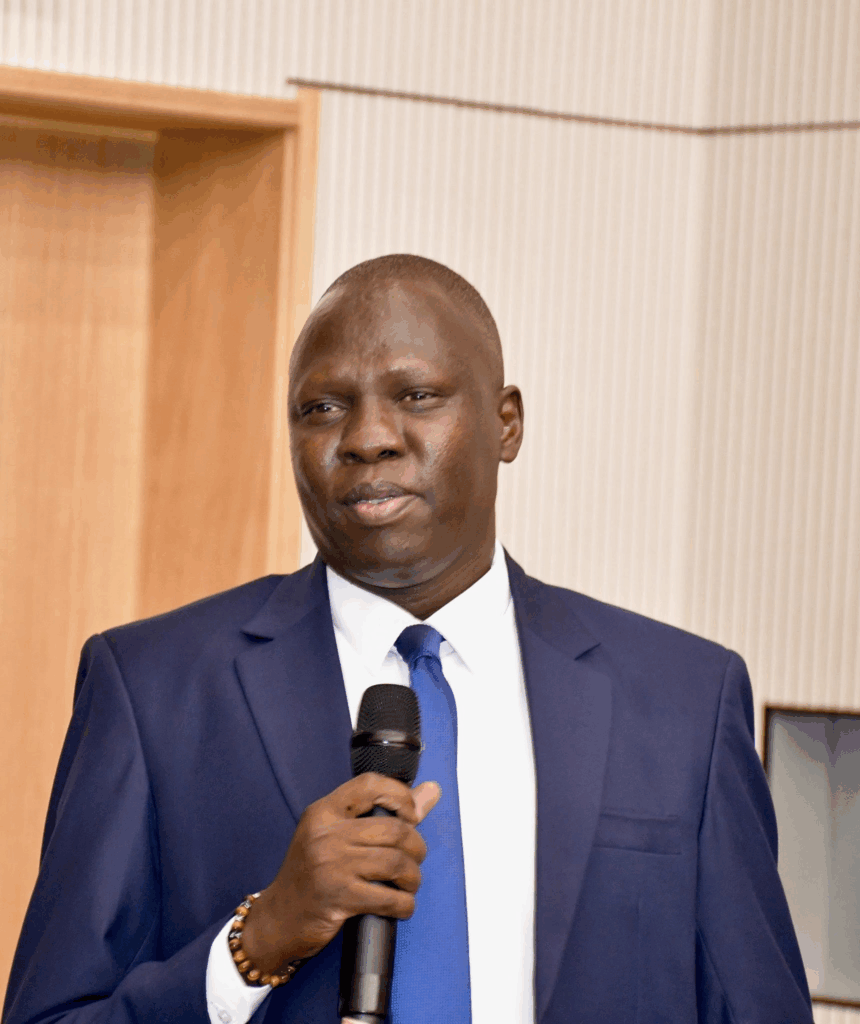

In the late summer and early fall of 2025, Mongolia’s political terrain shifted with the force of a Gobi desert storm. The country’s dominant ruling party, the Mongolian People’s Party (MPP) – a fixture in power for most of the past two decades – descended into a bitter leadership battle, while its main rival, the Democratic Party (DP), emerged from months of disarray to anoint a new, reform-minded chairman. These twin developments, unfolding against a backdrop of economic stagnation, systemic corruption, and growing public anger, are not mere political theater: they signal a potential realignment of power in Ulaanbaatar, with ripple effects for Mongolia’s delicate balancing act between China, Russia, and the United States. For a nation long lauded for its “managed succession” in post-Soviet democracy, 2025 marks a turning point – one that could either strengthen its democratic institutions or plunge it into a new era of gridlock. The Democratic Party’s Reboot: Tsogtgerel Odon’s Rise to the Helm For years, the DP has lingered in the MPP’s shadow. As Mongolia’s largest opposition party, it holds 42 seats in the 126-member State Great Hural (Parliament) – a respectable showing, but far short of the MPP’s 68-seat majority. Plagued by internal factionalism and unable to capitalize on public frustration with the MPP’s handling of the economy and corruption, the DP risked becoming a marginal player. That changed on August 31, 2025, when its National Policy Committee elected Tsogtgerel Odon as chairman, ending months of uncertainty following the resignation of former leader Gantumur Luvsannyam. Tsogtgerel’s victory was decisive. In the first round of voting, the 48-year-old secured 196 votes out of 314 participating committee members – crushing rivals Purevdorj Bukhchuluun (82 votes), Bayarmaa Judag (33 votes), and Otgonbat Barkhuu (3 votes). A planned runoff became unnecessary when Purevdorj and Bayarmaa withdrew, cementing Tsogtgerel’s uncontested win. The Supreme Court formalized his mandate on September 18, dispelling procedural uncertainties that had left the DP in administrative limbo and clearing the way for the party to regroup ahead of the 2028 parliamentary elections. Tsogtgerel’s ascent represents a generational pivot for the DP. Unlike the party’s older guard, which cut its teeth in the 1990 democratic revolution that ended communist rule, Tsogtgerel embodies a “technocratic pragmatism” shaped by business and governance experience. He leads Teso Corporation, a major Mongolian firm, and has served as an adviser to former Prime Minister Altankhuyag Norov and head of the DP’s Uvs Province branch. Elected to Parliament twice, he has led the DP’s parliamentary faction since 2022, giving him both grassroots credibility and insider knowledge of Mongolia’s political machinery. In his victory speech, Tsogtgerel framed the DP’s mission as “winning elections by delivering for Mongolians,” not just opposing the MPP. His platform targets three pressing issues: anti-corruption reform (elite wealth and the perception of corruption drove former Prime Minister Oyun-Erdene Luvsannamsrai from office in June), digital governance to streamline bureaucracy, and sustainable mining regulations to ensure resource wealth benefits ordinary citizens rather than elite oligarchs (a top public concern, per a May 2024 Sant Maral Foundation poll that named “mining corruption” as the nation’s biggest problem). These priorities resonate deeply with urban professionals and disillusioned youth – demographics the DP has struggled to win over in recent cycles. The stakes could not be higher for the DP. Tsogtgerel’s leadership is a last chance to revive the party’s fortunes: if he can unify its fractious wings – including populist rural supporters and urban reformers – it could erode the MPP’s supermajority in the 2028 election, ushering in a coalition era reminiscent of the 2010s. Failure, however, would consign the DP to irrelevance, leaving the MPP to dominate unchallenged – a scenario that risks further entrenching the corruption and stagnation voters increasingly reject. The MPP’s Civil War: Amarbayasgalan vs. Zandanshatar While the DP found its footing, the MPP descended into chaos. The infighting began earlier in 2025, when Oyun-Erdene resigned amid a corruption scandal sparked by public outrage over his son’s lavish lifestyle engagement party. In the aftermath, Zandanshatar Gombojav – a 55-year-old conservative with deep ties to Mongolia’s mining elite – assumed the premiership. Zandanshatar then consolidated power by holding both the prime minister’s office and the MPP chairmanship – a move Amarbayasgalan Dashzegve, the 44-year-old speaker of parliament and leader of the MPP’s “Youth Reformists,” condemned as “undemocratic” and a threat to checks and balances. Tensions boiled over on September 27-28, at the MPP’s Eighth Small Conference (Baga Khural) in Ulaanbaatar. The meeting began with the purge of 49 members (some by request, others for holding state offices) and the elevation of local party leaders to replace them, foreshadowing the factional battles to come. The main event, the chairmanship election, pitted Amarbayasgalan against Zandanshatar in a two-round showdown that laid bare the party’s ideological and generational divides. Under MPP rules, a chairman needs a two-thirds majority to win outright. In the first round, Amarbayasgalan secured 56.1 percent of the vote, while Zandanshatar took 44 percent – both falling short. Instead of negotiating a compromise, Zandanshatar and his core supporters boycotted the second round. With 321 members remaining (meeting the two-thirds quorum), Amarbayasgalan won 257 votes – 85.67 percent of the total. The MPP scheduled its 31st plenary meeting (Ikh Khural) for November 15–16, 2025, to formally ratify the result, with a 90-day timeline for finalization (60 days to transfer registration to the Supreme Court, plus a 30-day review). The election was more than a leadership change – it was a rejection of the MPP’s old guard. Amarbayasgalan’s “Youth Reformists” (officials under 45) came of age during Mongolia’s 2000s mineral boom and its subsequent bust; they campaigned by focusing on youth unemployment (which remains at around 15 percent), a mining sector that controls 70 percent of GDP but enriches only a few families, and a small-and-medium-enterprise (SME) sector that creates over 50 percent of jobs but receives just around 20 percent of available credit. Zandanshatar’s “Establishment Conservatives” (average age over 50) faction defended the status quo, warning that rapid reform would destabilize an economy already struggling: Mongolia’s GDP growth for the first half of 2025 was 5.6 percent, well below projections. The Asian Development Bank (ADB) had forecasted 6.6 percent growth for Mongolia and the World Bank predicted 6.3 percent. In addition, the value of coal exports dropped over 40 percent in the first half of 2025, and the general government budget balance posted a deficit of 758 billion tugrik ($211 million). Yet Amarbayasgalan’s win is not a panacea. Zandanshatar retains control of the executive branch and a loyal cadre of party members, raising the risk of “cohabitation deadlock” – a scenario the MPP knows well. In the 2010s, similar factional strife diluted the party’s reform agenda, leaving key issues like mining monopoly reform unaddressed. The party’s November plenary meeting will be a critical test: if Amarbayasgalan cannot broker compromises (such as including conservatives in key committees), the MPP could splinter further, undermining its ability to govern. The Roots of Unrest: Economic Malaise and Systemic Corruption The leadership battles in both parties are symptoms of deeper societal crises. Mongolia’s economy remains tethered to coal and copper exports, leaving it vulnerable to global commodity price swings. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) projects 2025 GDP growth at 6.0 percent – a rebound from 2024, but one driven by temporary coal shipment increases rather than structural reform. Inflation lingers at around 9 percent, eroding household purchasing power, while household debt has ballooned. 30 percent of Mongolians still live below the poverty line. Fiscal profligacy – exacerbated by pre-election spending – threatens macroeconomic stability. Corruption is the tinderbox. The 2022 coal theft scandal, which siphoned billions of dollars (equivalent to over 10 percent of annual exports), shattered public trust in the MPP. Oyun-Erdene’s downfall this summer only amplified these concerns, with investigations revealing how elite networks have captured mining rents. Transparency International ranked Mongolia 114st out of 180 countries on its 2024 Corruption Perceptions Index – proof that patronage networks persist in both major parties, stifling meritocracy and equality. Environmental degradation compounds these woes. Overgrazing and unregulated mining have accelerated desertification, while “dzuds” – deadly winter disasters that combine blizzards and livestock starvation – have become more frequent. The 2023–2024 dzud killed over 8 million livestock (12 percent of the national herd), devastating herder communities that form the MPP’s rural base. Climate models predict more such disasters, forcing leaders to balance resource extraction with sustainability – a challenge both Tsogtgerel and Amarbayasgalan have invoked but not yet outlined concrete plans to solve. These crises trace to Mongolia’s post-Soviet transition. The 1990s “shock therapy” privatizations birthed a class of oligarchs, while resource booms masked governance deficits. Today, 15 percent youth unemployment and mass migration to Ulaanbaatar (where around 50 percent of Mongolians now live) have strained infrastructure, breeding a volatile mix of apathy and activism. Mongolia’s political upheaval this year is a reckoning: voters are demanding change from a system that has failed to deliver on the promises of democracy. Geopolitical Ripples: Balancing Giants in a New Era Mongolia’s domestic turmoil has implications beyond its borders. Sandwiched between China and Russia – its two largest trading partners – and courted by the United States via its “Third Neighbor” strategy, Mongolia’s foreign policy hinges on a delicate balance. The 2025 leadership changes could tilt that balance. For China, Amarbayasgalan’s win may accelerate cooperation. China absorbs over 60 percent of Mongolia’s exports, and Amarbayasgalan’s faction has long supported the multibillion-dollar Power of Siberia 2 gas pipeline project (which will carry 50 billion cubic meters of Russian gas to China via Mongolia annually, generating $1 billion in transit fees for Ulaanbaatar). Zandanshatar’s conservatives had delayed the project, demanding better terms, but Amarbayasgalan is expected to push for its ratification by year’s end. He may also revive the Ganqimaodu-Gashuun Sukhait railway in the South Gobi region, a critical link for coal exports to China – good news for Beijing, which needs stable coal supplies to diversify away from Australia and Indonesia. Russia has reason for cautious optimism. While Amarbayasgalan’s focus on China may raise concerns, the Power of Siberia 2 remains a shared interest: Russia stands to earn billions annually from gas sales to China, a lifeline as it decouples from European energy markets. Amarbayasgalan has also signaled support for expanded military cooperation with Russia, including joint border patrols, a priority for the Kremlin amid tensions with NATO. The wild card is whether Amarbayasgalan will demand a larger share of domestic gas from the new pipeline, which could test bilateral ties but is unlikely to derail the project. For the United States, the shift is a setback. Washington quietly backed Zandanshatar’s conservatives, viewing them as more receptive to U.S. aid (over $50 million pledged since 2023) and annual “Khan Quest” military drills. Amarbayasgalan, by contrast, has dismissed U.S. aid as “token gestures” that fail to address Mongolia’s around $40 billion external debt (around 150 percent of GDP). While he is unlikely to cut ties entirely – Mongolia values U.S. support in international financial institutions – he will prioritize Sino-Russian partnerships. This was evident in September, when China hosted “Border Defense Cooperation 2025” drills with both Mongolia and Russia—a rare joint exercise U.S. officials saw as a snub. The DP’s Tsogtgerel adds another layer of complexity. His corporate background may boost investor ties with foreigners, but the DP has a history of anti-China rhetoric, fueled by historical grievances over territorial disputes. If Tsogtgerel leans into this to rally rural supporters, it could complicate Mongolia’s economic relationship with Beijing – a risk for a nation that depends on Chinese demand. Conclusion: A Pivotal Moment for Mongolia’s Democracy Mongolia’s 2025 political earthquake is not the end of its struggles – it is the beginning of a critical phase. The DP’s revival offers a glimmer of competitive democracy, while the MPP’s infighting forces a reckoning with its decades of dominance. For both Tsogtgerel and Amarbayasgalan, the next six months will be defining: Tsogtgerel must unify the DP and translate his platform into tangible policies, while Amarbayasgalan must navigate the MPP’s November plenary meeting and deliver on his reform promises. The stakes are high. Success could lead to a more inclusive, accountable political system – one that balances economic growth with equity and environmental sustainability. Failure could plunge Mongolia into gridlock, allowing corruption and oligarchy to deepen and risking instability that spills into its relations with China and Russia. For the international community, Mongolia’s trajectory matters. It is a rare example of stable democracy in Central Asia, and its ability to manage political change while balancing great powers offers a model for the region. As one Mongolian political analyst put it: “2025 is not about choosing between the MPP and the DP – it’s about choosing between a democracy that works for all or one that works for a few.” The world is watching to see which path Mongolia takes.