Copyright thebftonline

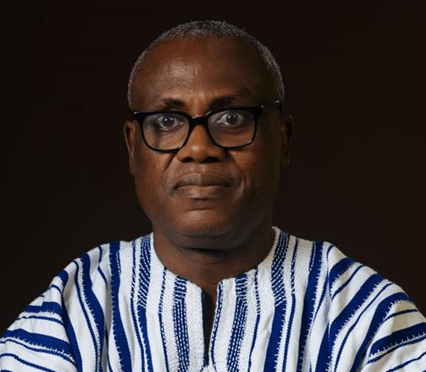

By Raymond DENTEH Ghana’s palm oil sector stands at a strategic crossroads. Once the heart of West Africa’s palm oil production, Ghana now trails global competitors, despite enjoying some of the most favourable agro-ecological conditions in the tropics. Today, the country paradoxically imports palm oil products, directly affecting currency stability, food sovereignty, industrial competitiveness, environmental safety, and rural livelihoods. At the core of this challenge lies a structural reality: over 60% of Ghana’s crude palm oil is produced by artisanal and small-scale processors, many of whom rely on outdated technology and traditional processing methods. These mills typically extract just 9–12% oil, compared to 19–23% achieved by industrial mills, according to the Ministry of Food and Agriculture (MoFA), Wageningen University, and the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR). This results not only in low yields, but also poor-quality oil characterized by high moisture, high dirt content, and elevated Free Fatty Acid (FFA) levels above acceptable industrial standards. Consequently, artisanal millers are confined to low-value informal markets, while refineries in Ghana import Crude Palm Oil l to meet industrial needs — undermining local jobs and exerting pressure on the Ghana Cedi. Put simply, Ghana is losing almost half of its potential oil palm not on the farm, but at the processing stage — following already low yields on smallholder farms. No investment in the oil palm sector will succeed without a deliberate strategy to intensify yields both on-farm and at the mill level. A National Stability Agenda, Not Merely an Agricultural Issue For years, the policy debate on palm oil has focused on plantation expansion. Yet the most immediate, inclusive, and cost-effective gains will come not from clearing new land, but from intensifying yields on current plantations and upgrading the processing backbone of rural economies. Modernising artisanal mills strengthens Ghana in four strategic ways: Protecting the Cedi UN Comtrade and World Bank data confirm that Ghana continues to import palm-oil products annually. As global prices fluctuate and foreign-exchange access tightens, increasing domestic production protects reserves and supports exchange-rate stability. Securing Industrial Growth Local manufacturers — including Wilmar Africa, Avnash, BOPP, and TOPP — often supplement supply with imports because artisanal oil does not meet industrial standards. Upgrading community mills would provide stable, refineable feedstock and strengthen our manufacturing base. Empowering Rural Women and Youth Women constitute the majority of artisanal mill labour. Evidence from Solidaridad and MoFA shows that providing women with access to semi-mechanised technology improves incomes, health, and household resilience. Meanwhile, youth gain skilled employment in machine operation, maintenance, logistics, and quality management. Reducing Rural-Urban Drift Vbrant rural enterprises anchor communities, reduce youth migration pressures, enhance social cohesion, and strengthen local economies. Modern mills can serve as rural industrial hubs, promoting peace and economic stability. Public Health and Environmental Imperatives Environmental and health risks from outdated milling practices are often overlooked. Many artisanal mills discharge untreated Palm Oil Mill Effluent (POME) into rivers and streams, damaging aquatic ecosystems and threatening downstream agriculture. In addition, using firewood, palm residues, and sometimes tyres or plastics for heating exposes women and children to dangerous smoke and toxic emissions. Studies published in Environmental Health Perspectives and FAO guidelines emphasize the dangers of chronic particulate exposure. Upgrading boilers, using clean fuels, and installing effluent ponds are therefore public-health necessities, not optional upgrades. The Proven Business Case for Upgrading Upgrading does not require reinventing the wheel. Demonstrated field experience shows that replacing manual presses with screw presses, adopting proper fruit handling, and applying basic quality controls dramatically improve output and quality. Solidaridad’s SWAPP programme recorded extraction efficiency increases from roughly 9% to 15% after equipment upgrades and operator training. Similar results have been achieved in Asia through IFC-supported SME upgrading programmes. Semi-mechanised mills are: More efficient and more profitable Safer and cleaner Easier to finance More attractive to industrial buyers These improvements are not theoretical — they have been demonstrated in Akyem, Agona, Asankragua, Kwaebibirem, and other major palm belts. TCDA’s Role — Standards, Finance, and Market Confidence The Tree Crops Development Authority (TCDA), established under Act 1010 (2019), has a mandate to formalise and strengthen value chains for tree crops, including oil palm. TCDA can lead a coordinated mill-upgrade programme anchored in: Licensing and classification of artisanal mills Enforcing minimum standards for presses, boilers, and effluent systems Training and certifying mill operators through TVET institutions Linking compliant mills to industrial offtakers Partnering with financial institutions to provide equipment leasing and credit Prioritising women’s processing cooperatives This mirrors successful approaches in Malaysia and Indonesia, where upgrading community mills — not just expanding plantations — formed the foundation of competitive palm oil industries. From Traditional Courtyards to Modern Rural Industry Ghana does not need to eliminate artisanal mills; it must upgrade and formalise them, ensuring they become dignified, productive rural businesses. This requires: Cleaner, safer processing environments Steam-based cooking rather than open fires Proper fruit handling and sterilisation Effluent ponds and composting systems Basic record-keeping and quality assurance Access to equipment leasing and finance This hybrid model — blending local enterprise with industrial standards — is both practical and inclusive. Conclusion — A National Duty to Modernise from the Bottom Up A resilient and prosperous Ghana is built on productive and dignified rural livelihoods. Modernising artisanal palm oil mills will: Increase domestic production and save foreign exchange Strengthen the cedi Support local manufacturing Improve rural incomes and job quality Enhance public health and environmental safety Empower women and youth Reduce rural-urban migration pressures Across palm-growing districts today, Ghana’s agro-industrial future is being shaped not only by plantations or factories, but in the smoky courtyards where rural women struggle with manual presses. Those courtyards can — and must — become clean, efficient, semi-mechanised rural factories. When they do, Ghana will move closer to currency stability, rural prosperity, and agricultural sovereignty. The pathway is proven. The case is clear. The time to act is now.