Mobile phones in schools: ‘I’d tell pupils to put their phone away and then it would be constant conflict throughout the lesson’

By Ian Swanson

Copyright scotsman

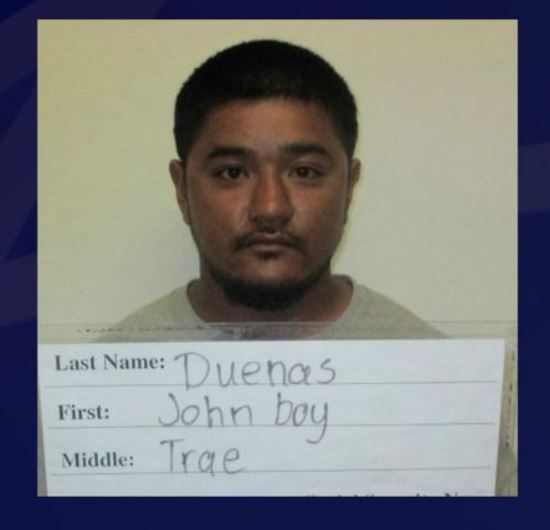

Maths teacher Emily Borrill said pupils would spend their time watching TikTok or messaging each other rather than concentrating on their work. She told how she was hit on the head as she broke up a fight sparked by messages pupils had been exchanging on their phones. And she argued a solution to the problem required leadership from the council to introduce a consistent policy on phones rather than leaving it up to individual schools or teachers to set their own rules. The council has already agreed to ban phones from the city’s primary schools and it plans a consultation on a ban in secondary schools. Two high schools – Portobello and Queensferry – are currently running a trial scheme where pupils must lock their phones in pouches during school hours and only unlock them as they leave at the end of the day. Ms Borrill, who has taught in several Edinburgh schools and was part of a deputation to the last education committee to press for a ban, said: “I remember being quite shocked when I first started at just how prevalent mobile phones are in the classroom, all the social spaces and everywhere, even though the policy was that phones should be off and away. “It’s so difficult to enforce that because they’re so addictive and they’re much more interested in what’s on their phones than what they’re being asked to do in class. And they’re so accessible if they’re just in your pocket.” She said children were used to having their phones with them all the time. “They’ve never known anything else than just growing up with these devices so close by. It’s not that they’re trying to misbehave, it’s a compulsion for a lot of them. “One teacher said lots of students had told him they spend more than 10 hours a day on their phone. They’re never not on their phone, so when they get into a classroom it’s just the same. “They’re scrolling, watching TikTok, they’re on Instagram, they’re messaging each other, they’re on Snapchat. Sometimes they’re taking photos in the lesson, watching YouTube, playing games sometimes.” She said it was often the first thing she said to a pupil when they came into the classroom, to put away their phone. “But then it would be constant conflict throughout the lesson because you’d tell them and they’d put it away and then they’d get it out again, or you would tell them to put it away and they would just refuse point blank. “Then you’d have to escalate it – if they just said no, the only thing you could do was send them to speak to the head of department or deputy head or whoever. It would take up so much leadership time, they didn’t have time to see to all the cases. So if it doesn’t happen, they know they can get away with it. “Things like that really undermine your teaching and it takes up so much class time. “It’s a constant battle and it feels like such an unnecessary fight to be having. It’s so frustrating.” She said she had heard a story about a teacher at one school who told a pupil to put his phone away and the pupil threw the phone at his face. “I once had to break up a fight – S1s were slapping each other and pulling each other’s hair, provoked by rumours and things they had been sending each other on their phones. It erupted into this spat in the front of my class, I stepped in and broke it up and I got hit in the head – I was pregnant at the time, so it wasn’t great.” Another aspect of the concern about pupils using their phones at school is the type of material they sometimes access. Ms Borrill said: “It’s awful the stuff they’re sending each other – porn, violent images, kidnapping, horrible stuff they can’t unsee. “I think phones are bad for kids at all times, but that’s up to the parents. Obviously, even if there is a ban on phones in school, they can still send each other stuff outside of school. But I think there’s a heightened danger when it’s at school because they’re sitting round in circles on their phones saying ‘Look at this’.” And she said although parents and teachers were mostly in favour of a ban, it was a big change which needed the council to make the decision. “It needs this leadership from the top,” she said. “What’s happened is the Scottish Government policy is ‘We realise phones are bad in the classroom but we’ll leave it up to local authorities’. Then the local authorities say ‘Yes it’s bad but we’ll leave it up to headteachers’. And the headteachers say ‘It’s bad but we’ll leave it up to individual teachers in the classroom’. “And individual teachers say ‘We’re all having to fight all these battles every single lesson when we could just have a simple blanket system that makes everyone’s life easier.'” Ms Borrill said the pilot of lockable pouches at Portobello and Queensferry high schools seemed to be working well. “One teacher told me they had been introduced without fuss and had an instant impact on behaviour and concentration. Another was sceptical that it would work, but said now no-one was on their phone in any of their classes, almost overnight.” And she argued pupils themselves would come to welcome such a policy. “Where they’ve introduced these pouches, if you ask the pupils before the ban they’re about 50-50 in favour of it or not, but after the ban they’re much more in favour because they realise that, oh wow, I can actually concentrate and talk to people. Anecdotally, where the ban has happened, they’re talking to each other at lunchtime like normal people again. “Staff say it’s just transformative to how you can teach and get attention from the pupils. It just seems a no-brainer.”