Copyright Slate

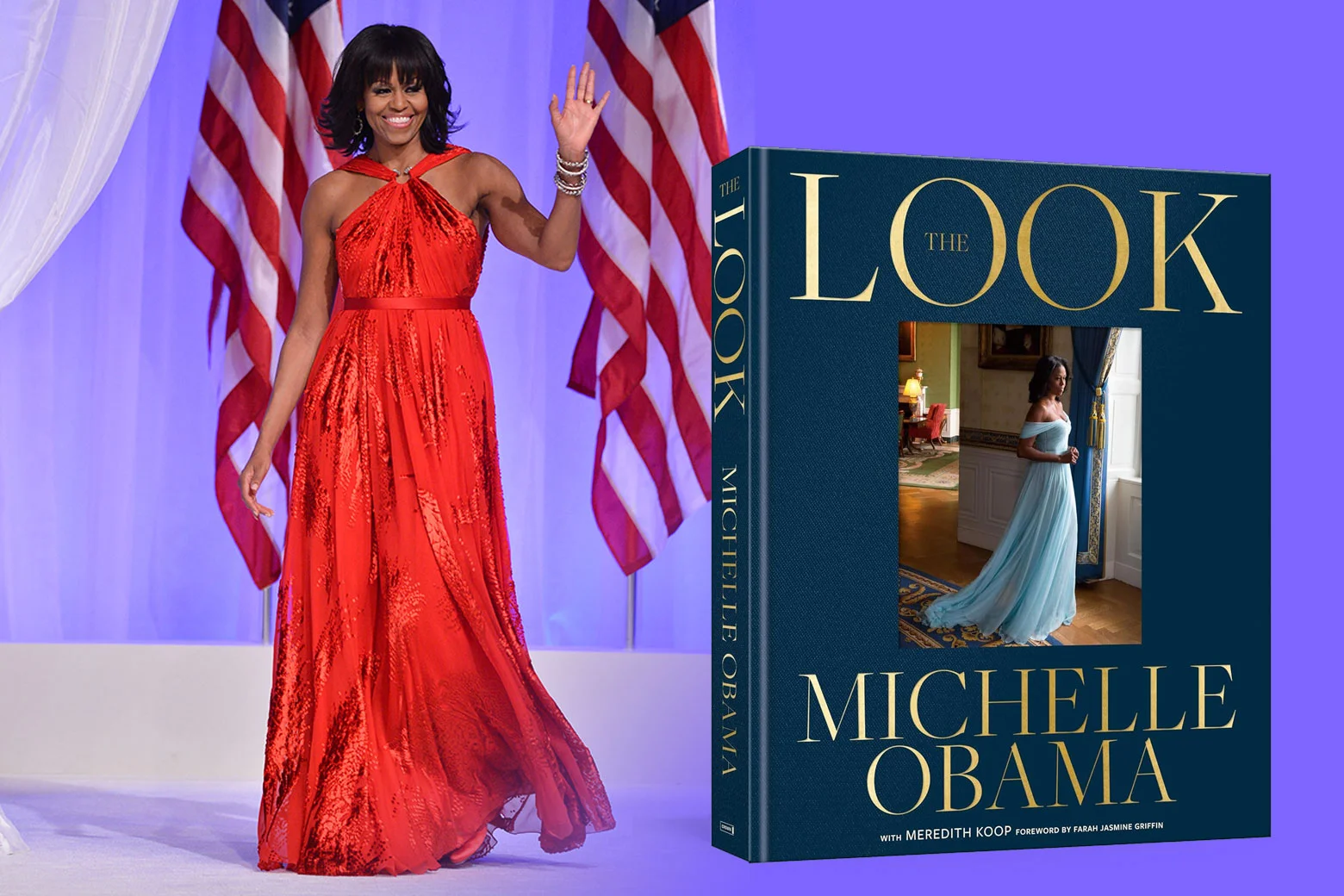

Sign up for the Slatest to get the most insightful analysis, criticism, and advice out there, delivered to your inbox daily. Michelle Obama enjoys a nearly unparalleled degree of public esteem. YouGov ranks her No. 2 on its list of most popular public figures, just behind Jimmy Carter. (Barack is No. 4.) In 2018 she ended Hillary Clinton’s 16-year streak as America’s most admired woman according to Gallup. Obama retained the honor through 2020, the last year the poll was conducted. No one else came close to beating her. It’s not just that people love Obama as a person. Americans want her in politics. In a July 2024 poll that posed hypothetical presidential matchups between Donald Trump and various Democratic contenders, including Joe Biden, only Obama beat Trump, and handily so—50 percent to 39 percent. This says at least as much about the hollow, unimaginative Democratic Party pipeline as it does Obama’s appeal, but the data stands. When she speaks, the country listens. This might have made Obama a natural leader in this moment of acute American catastrophe. Not in elected office, a position she does not want, but as a figure to educate and galvanize the masses against a swing toward Christian nationalist autocracy. That’s not the route she has taken. In her post–White House years, she has levied her popularity for personal enrichment and cultural clout rather than any political ends. With their production company and deals with Netflix and Spotify, the Obamas have created a cash-printing entertainment empire that includes Obama’s previous two books: Becoming, a depoliticized memoir that suggested we meet Trump’s first presidency with optimism, and The Light We Carry, an advice manual for personal growth and finding happiness. Both releases have associated workbooks, filled with writing prompts and habit-tracking forms to help optimize one’s relationships, home life, and self-care. In that tradition, Obama’s new book, The Look, cements her status as a self-improvement icon and lifestyle influencer with little interest in the state of our union. Arriving one year into the horrors of Trump 2.0 and published on Election Day, no less, the coffee-table book is a photo-rich dive into how Obama found her style as the first lady. Focused primarily on clothing, with some detours into hair and makeup, The Look explores the biggest fashion moments of Obama’s time in the public eye. She bills it in the introduction as “a celebration of confidence, identity, and authenticity.” In previous speeches and writings, Obama has reflected on the difficulty of being one of the most well-known figures in the world, and she does so at length in The Look. She writes well, and honestly, about the havoc it can wreak on one’s sense of self to have to dress every morning for what would be, for the majority of people, the most visible day of their lives. Seeing a joyful Black family in the White House being celebrated as models of grace and class while unabashedly embracing Black culture was a meaningful milestone for scores of Americans. Its power can also be measured by the way it radicalized others and prompted right-wing trolls to relentlessly criticize her looks. “I understood that without me controlling my own narrative, people’s racism and misogyny would attempt to take over and define me,” she writes. Style is no small part of a first lady’s job, as she is more often seen than heard and has no defined policy role. Occupied by inconsequential appearances and White House homemaking, she is expected to be the country’s wife and mom, a comforting figure that lends softness and warmth to the president’s persona. Between the details of garment fittings and quick changes, The Look functions as an account of how Obama understood her job description. At one point, she characterizes it thus: “Every look had to meet my baseline criteria: could I give anyone a hug at any moment?” Like Beyoncé or Taylor Swift, Obama has achieved a level of fame and esteem that guarantees the runaway success of every product she releases. Plenty of devoted fans will eat up the stories she unspools in The Look, such as how she tried to stay warm in her pear-colored ensemble from Isabel Toledo at Barack’s 2009 inauguration, or the way she chose the white pinstriped suit she wore to the 2004 Democratic National Convention, at which Barack gave the speech that would propel him to national fame. Other readers may balk at the level of drama she tries to generate behind every fashion moment, as if she were Barack narrating the bin Laden raid in Abbottabad. The year that Obama had to pick that DNC outfit, she writes, her lunch break to-do lists were always packed: “Buy birthday present for Sasha’s friend, pick up burrito bowl, get a dress for the DNC.” A trip to a department store was a “mad dash”; finding the suit in time was “a miracle.” I’m sure being a political spouse is stressful, with demanding schedules and high-pressure events—not to mention the inexorable self-erasure. But I grew weary of reading about how hard getting dressed has been for Michelle Obama, an international superstar with a net worth topping $70 million, in a coffee-table book containing hundreds of photos of her looking gorgeous, beaming, and clad in the finest garments those millions could buy (or receive as gifts on behalf of the U.S. government). Still, I believe that fashion matters, as both a personal pursuit and a political one. I have never been one to scoff at news analysis that draws meaning from the clothes public figures wear; I don’t think, as some journalists do, that it demeans or diminishes women in politics to evaluate the carefully curated aesthetics they choose to embody. The Look, an unprecedented project among first ladies, may be the only first-person book to give such devoted treatment to the place of image-making in presidential politics. Some of the The Look’s best commentary on that topic comes from the members of Obama’s style and beauty team, who contribute writing about the nuts and bolts of zhuzhing up one of the most famous women in the world. One fascinating chapter is authored by Meredith Koop, the young stylist Obama hired to work full time at the White House, who explains the myriad technical considerations of Obama’s wardrobe. Often, Koop and her tailor would make a wrap dress a “faux wrap dress” so Obama could sit without flashing the cameras, or add a long zipper up the back of a garment so she wouldn’t have to disrupt her hair and makeup by pulling it over her head. The forethought required of a presidential stylist is evident in Koop’s recollections of how she dressed the former first lady for special events, in such choices as a custom, intricately beaded J. Mendel top, designed in 2012 with three-quarter-length sleeves that could be shortened into cap sleeves with a seam ripper should the day be warmer than expected. (It was.) It is a treat to read about Koop’s back-and-forth with Versace on the dress for Obama’s final state dinner, with Italy, constructed in a rose-gold version of the brand’s trademark chain mail. Seeing how the final product came to be, through beautifully reprinted sketches and a recounting of the negotiation between designer (presenting a vision) and stylist (hewing to the demands of the office), gives new meaning to the dazzling design. Another highlight is the chapter on Obama’s hair. It tackles the conundrum of styling her Black hair for a largely white audience, which ruled out braids or other protective styles, without the overuse of heating implements that could cause lasting damage. “I always said that I wanted to leave the White House with my sanity, my family, and my hair healthy and intact,” Obama recalls. One of her hairstylists, Yene Damtew, writes that it was her job to make the first lady’s hair “consistent, recognizable, and never part of the media conversation.” She made good use of extensions and wigs, which were new to Obama, to grant her versatility while saving her hair. Eventually, Johnny Wright, Obama’s main hairstylist for her first term, realized that her hair was starting to break from the daily styling of Barack’s reelection campaign. Seeking to give her a look that wouldn’t demand so much heat exposure, he sent her a “storyboard” to persuade her to get bangs. The haircut Obama explained at the time as her “midlife crisis” was actually “about health, not trends,” Wright writes. It’s a perfect example of how any simple, personal choice she made as a Black woman in the public eye could become international news and influence countless American women. But on other topics that could be equally edifying on the construction of the first lady’s image, Obama imparts superficial observations. Reflecting on how she navigated the line between cultural respect and appropriation on foreign trips, she writes that “one travel day could require up to three looks” and necessitate cursory research into what body parts need be covered when visiting houses of worship. There is a roundup of her magazine covers, a repetitive spread that ends up looking like a kindlier version of Warhol’s Mao portfolio, and a page paying tribute to “Looks That Went Viral,” which reprints such insightful social media reactions as “Mrs. O looks lovely :)” and “It’s safe to say we are all LIVING for those thigh-high boots.” Obama’s own fashion analysis is no sharper, often rendered in the tired prose of a middle-market women’s magazine. On brooches: “I loved the way they could add interest or a pop of color.” On Diane von Furstenberg wrap dresses: “Made me feel put-together and chic.” On cardigans: “The ultimate practical yet stylish piece.” The designers who created her outfits might have offered more-substantive fare. Instead, they show up only in gushing pull quotes. Narciso Rodriguez calls designing for Obama “the greatest honor of my career”; Tracy Reese says it was “an incredible moment for us as a brand”; for Maria Cornejo, “our world opened up to another client base.” I suspect that these interludes are supposed to engender respect for Obama, who made a point to champion American designers, designers of color, and little-known brands. Instead, they struck me as gratuitous and predictable, the kind of snoozers you’d scroll past in a press email. Obama writes that she tried not to let “any superficial focus hijack the message” of Barack’s presidency but eventually came to learn the “soft power” of fashion: “People looked forward to the outfits, and once I got their attention, they listened to what I had to say.” What did she have to say? She famously wore J. Crew and off-the-rack garments, wanting to appear welcoming and down-to-earth, ready to connect with any American. But in The Look, she studiously resists connecting that ethos with any specific opinion, much less a political ideology. One of the only actual policies she mentions supporting is the CROWN Act, a piece of federal legislation that would bar discrimination based on hair texture or style. It was introduced after Barack left office and never passed. It’s a baffling decision, especially since Obama makes multiple references in the book to the importance of style that supports “my message” and shows the world “who I am and what I believe in.” Then again, she has never had much of a taste for bold proclamations. In the White House, she claimed uncontroversial issues that barely brushed against public policy: supporting military families and getting kids into healthy living. Some of us assumed that she was treading lightly as the first Black woman to occupy the role. But today, it is clear that Obama was not playing 12-dimensional chess, curating a palatable persona to help sell her husband’s agenda. After nearly a decade in post–White House private life, she has not meaningfully deviated from her vantage of calm disinterest. She’ll dutifully stump for a candidate when a presidential election rolls around, and that’s about it. This places Obama in a rare position in the modern-day Democratic Party, which runs on the slavish (and misguided) desire to appeal to the broadest, blandest possible audience for the express purposes of electoral gain. Obama seems to share that desire, but for purposes that are unclear. She’s not running for office. She’s not gunning for social impact. What else is left? Her motivations appear to be simpler, the same as any other lifestyle guru selling inspirational content: money and fame. And there’s nothing inherently wrong with that. One might even argue that while Obama came to fame through politics, she drew admiration via parasocial connections rather than policymaking, so she has no responsibility to engage with matters of public concern. But most readers won’t have the privilege of turning off the politics parts of their brains while leafing through a book about life in the White House. Obama writes that her mission as a public figure is to “spotlight the stories and struggles of women” and, with her fashion, start conversations about “authenticity, self-expression, and empowerment.” This pablum reads like a dispatch from the simpler times of her husband’s presidency (or the more soothing, self-congratulatory corners of today’s influencer economy). In the Trump 2.0 era, Obama’s message sounds jarringly Pollyannaish amid the “stories and struggles” American women are now living: forced childbirth, resurgent misogyny, the gutting of Medicaid and safety-net programs, white nationalists and their sympathizers calling the shots in federal law enforcement. Whether we’re furloughed without pay from our government work, left hungry by our missing SNAP benefits, lonely after the disbanding of our campus club, or desperate to reunite with a loved one who was snatched off the street by a horde of masked men, Obama invites us to join her, a flock of ostriches sticking our heads into her closet. The Look strikes a particularly dissonant note when it bumps against consequential moments of the recent past. Obama tells the story of wearing a sleeveless Monse pantsuit for her speech at the 2024 DNC, when she “could feel the energy ripple through the crowd as people responded to my call to action, chanting, ‘Do something!’ ” We never hear the end of that story: What happened in the election after Obama’s address, which she claims “lit a fire in the audience, and far beyond”? It is an omission so obvious it feels like censorship. Instead, the DNC speech transitions into nearly a full page about a time people criticized Obama for wearing shorts. Decisions like these feel antithetical to a book whose entire premise suggests that fashion is meaningfully intertwined with politics. Multiple full-page photos are devoted to the plum Sergio Hudson getup Obama wore to Trump’s 2017 inauguration—but the only remarks on it come from Hudson himself, who understandably experienced the occasion as a personal triumph. For Obama’s readers, it was likely a day of grieving and fear. It would have been nice to hear how she felt while wearing that stunning outfit on the day she vacated the White House for the man who demanded the release of her husband’s birth certificate. In the parlance of her fellow influencers, it might have made her more relatable too.