Copyright stabroeknews

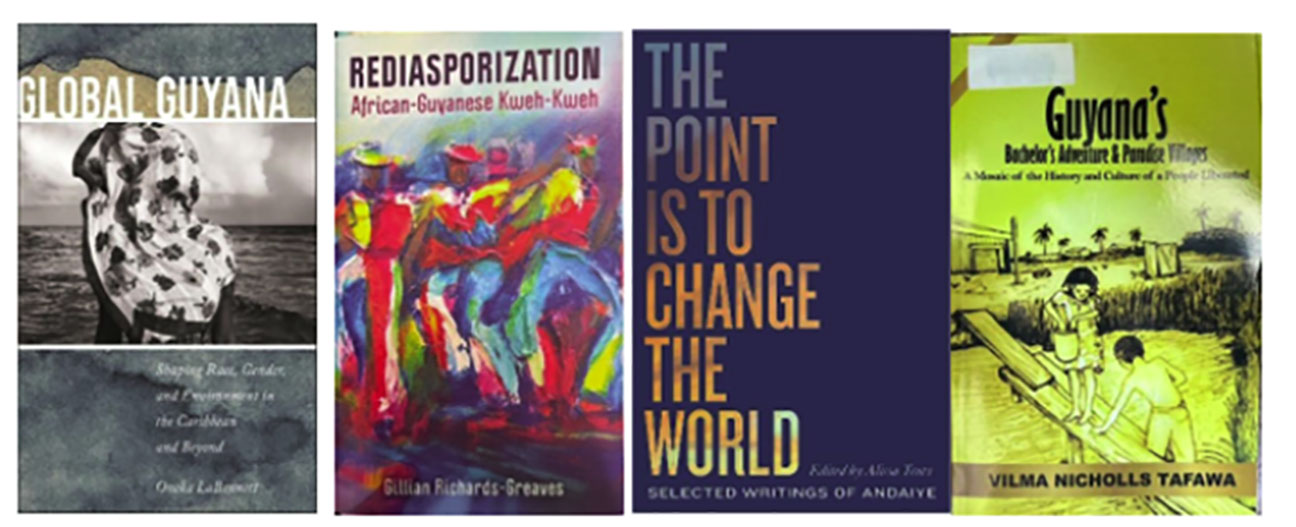

By Nigel Westmaas “Nah tek yuh mattie eye fuh see.” – Guyanese proverb (“Don’t rely on someone else’s view, see for yourself.”) One of the striking features of political and historical memory in Guyana is its persistent absence from the public record. Too often, those who write, discuss, or interpret Guyanese history ignore or distort events, overlook key details, or present only fragments of collective struggles, achievements, and organizational and individual efforts in the history of the country. The result can lead to sketchy understanding of our past that leaves the younger generation, and other publics disconnected from the deeper meanings of nationhood and memory. An aspirational history syllabus centred on Guyana would offer more than the recovery of facts; it would be an act of reclamation. It could help build national unity in a society shaped by ethnic diversity, colonial legacies, and enduring political tensions. Such a syllabus would ground education in the lived realities of Guyanese people, helping Guyanese to see themselves as active participants in a constantly evolving story. Philosopher Kwasi Wiredu argued that education should reflect the cultural and intellectual experiences of a people. For postcolonial societies, this means reclaiming intellectual independence and shaping education around their own histories and values. In Guyana’s case, a national syllabus must move beyond trite repetition of traditional narratives and centre instead on the stories, struggles, philosophies and consequential individuals that emerged. Teaching or transmitting Guyanese history, therefore, should not be limited to reciting dates or celebrating national milestones. It should examine the evolution of ideas about justice, human rights, resistance, ethnic division and identity, and self-determination. By tracing the effects of slavery, indentureship, colonial administration, and the long journey to independence and the post colonial society, the public will better understand how these legacies shape today’s inequalities, tensions and narratives. Because Guyana is multiethnic, a national history syllabus must include the experiences and contributions of Afro-Guyanese, Indo-Guyanese, Indigenous peoples, Portuguese, Chinese, and other groups. A balanced curriculum promotes empathy and respect for differences while reinforcing shared experiences, labour struggles, political mobilization, cultural exchanges, and acts of everyday resilience. But this shared story should not become a single, state-approved version of the country’s complex history. It must make room for contradictions within the national narrative and find ways to live with and learn from those tensions. Influenced by educators like Brazil’s Paulo Freire, a meaningful syllabus must not simply teach history – it must question it. Students and the public should learn to think critically about power, oppression, and social transformation. In Guyana, this means probing how colonial rule shaped social hierarchies, how race and class have influenced political organization, and how citizens have resisted, adapted, and imagined freedom before and after independence and republic status. Critical engagement can transform the individual, and the community whether in a home discussion, a Zoom meeting, a rum shop, or the official classroom, into a space for democratic learning. People would begin to see history not as something that simply happened in the past, but as something they actively shape. This awareness fosters civic consciousness and prepares young people, for instance, to confront the challenges of the present whether these challenges take the form of corruption, inequality, or environmental and border crises, with a sense of historical grounding and ethical purpose. The matter of historical memory The question remains: how does one develop a general syllabus on Guyana’s history? A syllabus, by its nature, is both structure and conversation. It outlines topics, readings, and themes, but it must remain open to revision. Guyanese history is likewise not static. New scholarship, oral histories, and cultural expressions continually reshape how we understand the past. Therefore, the syllabus must allow for overlap, debate, and the integration of emerging perspectives. Guyana possesses a rich tradition of philosophical reflection, though it has rarely been acknowledged as such. This neglect stems partly from the guilt, divisions, and disillusionment that accompanied both colonialism and independence and modern partisan political entanglements. A Guyanese syllabus must embrace this full intellectual range – from Indigenous cosmologies and oral traditions to the writings of labour leaders, poets, schoolteachers, artists, and scholars. Philosophy, widely conceptualised in this context, is not confined to the academy. It includes the moral reasoning embedded in folk tales, the collective wisdom of village life, and the critical voices that have emerged from every corner of the nation. Past figures like Joseph Ruhoman, whose philosophical contributions are either unknown or overlooked, remind us that not all the ideas shaping Guyanese nationhood are easily accessible. Equally, how well is it known that Brindley Benn, as minister of Community Development and Education in 1958, coined the post-independence motto “One People, One Nation, One Destiny”? The study of history and the making of a syllabus is, at its heart, an exploration of human experience. In Guyana, it means tracing how people have faced oppression and possibility, conflict and cooperation. A meaningful national syllabus should recover forgotten histories while examining how institutions like family, education, religion, and governance have evolved. It should also reveal the ways global and regional forces have shaped Guyana, and how Guyana, in turn, has shaped the wider Caribbean and the Americas. Jamaican scholar David Scott, reflecting on Jamaica’s own historical memory and consciousness, warned against treating history as a simple chronological story. He argued that formal national narratives often stabilize rather than question power. For example, Scott complained about the “exhausted nation-state” periodisation, giving examples such as the 1938 labour rebellions and the 1944 adult suffrage struggles in modern Jamaican history as recurring episodes in the Jamaican historical narrative. The same challenge applies to Guyana: to view history not as a closed narrative, but as a national process and one that should not be dictated or rewritten by any single political party to serve its own ends. Introducing the syllabus The following list offers a sample of potential subheadings (space does not allow for a further sub-division) and readings thereunder for an aspirational syllabus on Guyana, drawn mainly from books and articles. This is not a definitive or exhaustive list but rather a sample. Some texts overlap across the subhead themes. Many other valuable works are not included, as are materials from film, oral history, radio, and surviving television archives. Sports and cricket are also not represented in the bibliography or subheadings. Some of the works included here may serve as subjects of study, texts that reflect the very evolution of national thought while others may challenge established interpretations. The goal is not to establish a fixed canon or bibliography of themes, but to provide a foundation for continued exploration, critical inquiry and reference. Early and Indigenous Guyana Denis Williams, The Archaic of North-Western Guyana; Denis Williams, Ancient Guyana (1985); W H Brett, Indian Missions in Guiana (1851); Edward Goodall, Sketches of Amerindian Tribes 1814–1843 (1977); Mary Noel Menezes, Amerindian Life in Guyana (1982); Menezes (ed), The Amerindians in Guyana – A Documentary History (1979); Joshua Hyles, Guiana and the Shadows of Empire: Colonial and Cultural Negotiations at the edge of the World (2014); Janette Forte, About Guyanese Amerindians (1996) General and Colonial History Kimani Nehusi, A People’s Political History of Guyana 1838–1964 (2018); Henry Kirke, Twenty-Five Years in British Guiana (1898); James Rodway, History of British Guiana; A R F Webber, Centenary History and Handbook of British Guiana 1831–1931(1931); John Campbell, History of Policing in Guyana (1987); P H Daly, Story of the Heroes: The Assimilative State (1940); Lal Balkaran, Timelines of Guyanese History (2012); Henry Bolingbroke, A Voyage to the Demerary 1799–1806 (1807); Walter Rodney, A History of the Guyanese Working People, 1881–1905 (1981); Odeen Ishmael, The Guyana Story (2013); Winston McGowan, A Survey of Guyanese History (2018) Enslavement, Resistance, and Emancipation Marjoleine Kars, Blood on the River: A Chronicle of Mutiny and Freedom on the Wild Coast (2020); Emilia Viotti da Costa, Crowns of Glory, Tears of Blood; Michael Moohr, Economic Impact of Slave Emancipation (1972); Melissa Ifill, “The African Family in the Immediate Post-Emancipation Period” (2004–05); J O F Haynes, “Slavery and the Law” in Proceedings of the International Roundtable to Commemorate the 150th Anniversary of the Abolition of slavery (1984); Alvin Thompson, A Documentary History of Slavery in Berbice 1796-1834 (2002); Alvin Thompson, Unprofitable Servants (2002); Winston McGowan, James Rose & David Granger (Eds) Themes in African-Guyanese History (1998); Tommy Payne, Ten Days in August 1834 (2001) Labour, Economy, and the Village Movement Alan Adamson, Sugar Without Slaves (1972); Clem Seecharan, Jock Campbell: Sweetening Bitter Sugar (2005); Barbara Josiah, Creating Worlds: Mutuality and Finance among African-Guyanese; Eusi Kwayana, The Legend – Post Emancipation Villages in Guyana – Making World History (2016); Mohamed Shahabudeen, From Plantocracy to Nationalisation: A Profile of Sugar in Guyana (1983); Ashton Chase, History of Trade Unionism in Guyana 1900-1961 (1964); Arif Bulkan & Alissa Trotz, Unmasking the State: Politics, Society and Economy in Guyana 1992-2015 (2019); J Van Sertima, Our Colonial Currency: History of its Evolution (1959); Fenton Ramsahoye, The Development of Land Law in British Guiana (1966); Raymond Smith, The Negro Family in British Guiana: Family Structures and Social Status in the Village (1956); Vilma Nicholls Tafawa, Guyana’s Bachelor’s Adventure & Paradise Villages: A Mosaic of the History and Culture of a People Liberated (2025) Immigration, Indentureship, and the Making of a Plural Society Basdeo Mangru, Indians in Guyana (1999); Peter Ruhomon, Centenary History of the East Indians (1946); Clem Seecharan, Tiger in the Stars (1997) and Mother India’s Shadow Over El Dorado: Indo-Guyanese Politics and Identity 1890s – 1930s (2011); Cecil Clementi, The Chinese in British Guiana (1915) Mary Noel Menezes, The Portuguese of Guyana: A Study in Culture and Conflict (1992); Brackette Williams, Stains on My Name (1991); Brian Moore, Cultural Power, Resistance and Pluralism (1995); Joanne Collins-Gonsalves, The Portuguese in Business in Guyana 1835-1935: A History of Entrepreneurship, Expansion, and Diversification (2025); Leo Depres, Cultural Pluralism and Nationalist Politics in British Guiana (1967); Brian Moore, Race, Power and Social Segmentation in Colonial Society: Guyana after Slavery 1838-1891 (1987); Juanita de Barros, Order and Place in a Colonial City (2002); Roy Glasgow, Guyana: Race and Politics among East Indians and Africans (1970); L. Crookall, British Guiana or Work and Wanderings among the Creoles and Coolies, the Africans and East Indians of the Wild Country (1898); Peter Newman, British Guiana: Problems of Cohesion in an Immigrant Society (1964) Political and Constitutional Development Mohammed Shahabuddeen, Constitutional Development in Guyana 1621-1978 (1978); Jason Haynes, “The Constitutional Law of Guyana” in Oxford Handbook of Caribbean Constitutions (2020); Harold Lutchman, From Colonialism to Cooperative Republic (1974); Frank Birbalsingh, The PPP of Guyana 1950–1992 (2007); Nigel Westmaas, A Political Glossary of Guyana (2021); Frank Birbalsingh, The Peoples Progressive Party of Guyana 1950-1992: An Oral History (2007); Colin Palmer, Cheddi Jagan and the Politics of Power (2010); Judaman Seecomar, Democratic Advance and Conflict Resolution in Post-colonial Guyana (2009); Cecil Clementi, A Constitutional History of British Guiana (1937); Henry Jeffrey & Colin Baber, Guyana: Politics, Economics and Society (1986); E Greene, Race vs Politics in Guyana: Political cleavages and Political Mobilisation in the 1968 General Elections (1974) Race, Identity, Gender and Social Life Joseph Ruhoman, The Transitory and the Permanent: Being a Study and a Comparison of Values (1922); GHK Lall, Sitting on a Racial Volcano (Guyana Uncensored) (2013); Vibert Cambridge, Musical Life in Guyana (2015); George Mentore, Of Passionate Curves and Desirable Cadences (2005); Frank Thomasson, A History of Theatre in Guyana, 1800–2000 (2009); Eusi Kwayana, Buxton Friendship in Print and Memory (1999); Alissa Trotz (Ed), The Point is to Change the World: Selected Writings of Andaiye (2020); Hazel Woolford (Ed) An Introductory Reader for Women’s Studies in Guyana (2000); David Hinds, Ethno-Politics and Power Sharing in Guyana: History and Discourse (2010) Language, Folklore, and Cultural Expression John Rickford (Ed), Festival of Guyanese Words (1978); Hubert Devonish, Language and Liberation (1986); Richard Allsopp, Dictionary of Guyanese Folklore (1975) and Language and National Unity (1997); Charlene Wilkinson, “Language and Power” (2012); Eusi Kwayana, Gang-Gang (1997); Rupert Roopnaraine, The Sky’s Wild Noise: Selected Essays (2012); Gillian Richards-Greaves, Rediasporization: African Guyanese Kweh-Kweh (2020); Godfrey Chin, Nostalgias: Golden Memories of Guyana 1940-1980 (2008); Gemma Robinson (Ed), Martin Carter: University of Hunger – Collected Poems & Selected Prose (2006) Biography and Individual Lives Claudia Tomlinson, Jessica Huntley: A Pan African Life (2024); Baytoram Ramharack, Jung Bahadur Singh (2019); Baytoram Ramharack, Balram Singh Rai (2005); Patricia Mohamed, Janet Jagan: Freedom Fighter of Guyana (2024); Linden Lewis, Forbes Burnham: The Life and Times of the Comrade Leader (2024); Clem Seecharan, Bechu: ‘Bound Coolie’ Radical in British Guiana 1894–1901 (1999); Leo Zeilig, The Walter Rodney Story: A Revolutionary of Our Time (2022); Clem Seecharan, Cheddi Jagan and the Cold War 1946-1992 (2023); Selwyn Cudjoe, Caribbean Visionary: ARF Webber and the Making of the Guyanese Nation (2009); Cheddi Jagan, The West on Trial: My Fight for Guyana’s Freedom (1966); Forbes Burnham, A Destiny to Mould (1970); Clement Rohee, My Story, My Song (2021); Moses Nagamoottoo, Dear Land of Guyana: My Quest for National Unity (2023) Education and Intellectual Traditions M K Bacchus, “Education in the Pre-Emancipation Period” (1990); Norman Cameron, 150 Years of Education: Guyana 1808–1957(1964); Yvonne Stephenson, “The Power of Reading since Emancipation” (UNESCO 1984); Hazel Woolford, Social Issues Behind the Introduction of the Compulsory Denominational Education Bill of 1876 (1989) International Relations, National Defence, Boundaries, and Natural Resources Odeen Ishmael, The Trail of Diplomacy (2013)); Tyrone Ferguson, To Survive Sensibly or to Court Heroic Death (1999); David Granger, National Defence: A Brief History of the Guyana Defence Force 1965-2005 (2005); Barbara Josiah, Migration, Mining and the African Diaspora (2011); Oneka LaBennett, Global Guyana: Shaping Race, Gender, and Environment in the Caribbean and Beyond (2024); Sarah Vaughn, Engineering in Pursuit of Climate Adaptation Vulnerability (2022) Carl Greenidge, Empowering a Peasantry in a Caribbean Context: The Case of Land Settlement Schemes in Guyana, 1865-1985 (2001); Eusi Kwayana, A New Look at Jonestown: Dimensions from a Guyanese Perspective (2016); David Granger, Guyana People’s Militia (2008) and Guyana National Service (2008); Stephen Rabe, US Intervention in British Guiana: A Cold War Story (2005); Jay Mandle, The Venezuela Guyana Border Dispute (1983)