Copyright forbes

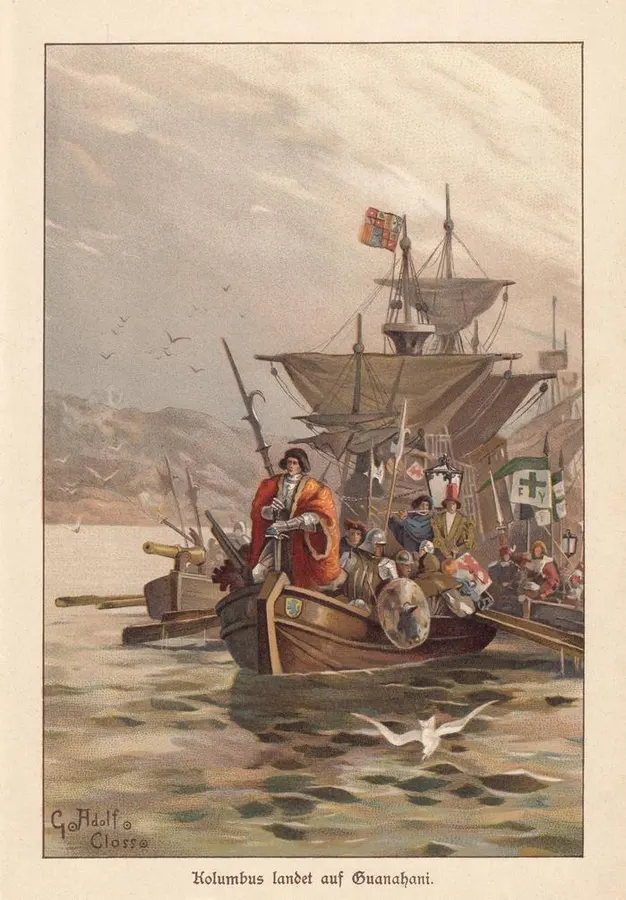

The ecological impact of Christopher Columbus’ arrival in the new world cannot be overstated. Here’s one of the many reasons why, explained by a biologist. When Christopher Columbus arrived in the Atlantic in 1492, he brought with him not just sailors, food and visions of the new worlds. His voyage, and those that followed, ignited what scientists now call the Columbian Exchange: the vast intercontinental transfer of species between the Old and New Worlds. Horses, cattle, pigs, wheat and even smallpox traveled in one direction across the ocean, while maize, tomatoes, potatoes and syphilis made the journey in the opposite direction. Among the most forgotten and ecologically significant travelers was an unintended stowaway: the common European earthworm. To most, the earthworm (Lumbricus terrestris) is a harbinger of fertile soil and healthy gardens. What many of us don’t realize is that, before Columbus came to America, much of North America had been earthworm-free for thousands of years. Why Were There No Worms In America? During the latest Ice Age, the greater part of northern North America was under ice cover, which ground down forests and stripped away entire topsoil layers. Whatever indigenous earthworm species were present in such regions were wiped out. When the ice retreated about 10,000 to 2,000 years ago, the soil left behind was new, unworked and earthworm-free. In all of these postglacial regions — the upper Midwest, the Great Lakes basin, New England and much of Canada — the forests created unique ecosystems that weren’t reliant on earthworms to decompose organic material. Forest floors were densely leaf-covered, gradually decomposing as a result of fungal and microbial action. This gradual decomposition created a spongy, layered leaf litter that insulated moisture, tended seedlings and offered habitat to insects and small animals. MORE FOR YOU Pre-Columbian forests north of the ice line were wormless by design. They lived just fine for many thousands of years without the critters that we now cite as a signal of healthy soil. The Accidental Arrival All of this changed with the transatlantic voyages of the late 15th century. Columbus’s vessels (and all the hundreds of European vessels that subsequently arrived) had soil as ballast, as well as live plant life, seed of crops and pots of herbs. Within the soil were buried cocoons of earthworms and live specimens of many of Europe’s species, such as Lumbricus terrestris, Aporrectodea caliginosa and Dendrobaena octaedra. No one intended to bring them. They were stowaways in the earth: a secret byproduct of transporting plants, provisions and ballast from continent to continent. As immigrants planted foreign produce or vessels unloaded ballast, the worms suddenly found themselves in fertile, wormless soil, rife for colonization. From there, earthworms wriggled their way slowly but inexorably into the forests of eastern North America. Centuries went by — first the coast, then inland by way of trade, agriculture and fisheries — before they became permanent residents of ecosystems that had not seen their ilk in over ten thousand years. The Worm That Changed The Woods The earthworm’s return to North America may appear harmless, even beneficial. However, in northern hardwood forests, their reintroduction led to a domino effect of ecosystem changes. As European earthworms burrow through leaf litter, they consume it rapidly. They, in turn, leave behind exposed soil beneath the trees, where once a thick layer of leaves protected moisture and nurtured seedlings. This alteration changes the very chemistry and structure of the soil. University of Minnesota biologist Cindy Hale has documented how earthworm invasion alters forest ecosystems. Her research, and others’, shows that native vegetation species such as trillium, sugar maple and trout lily are hindered from germinating once the litter layer is gone. In the absence of the layer, seeds dry out, and juvenile roots are exposed to direct sun and fluctuating temperatures. The result is a sharp reduction in forest undergrowth and seedling recruitment. In the meantime, earthworms infuse organic matter well beneath the soil’s surface, shifting the pattern of nutrients and releasing nitrogen more readily. These kinds of conditions often favor non-native plant life — like buckthorn and garlic mustard — that thrive in disturbed soils. In essence, European earthworms are “ecosystem engineers:” organisms that change their environment in physical ways, typically with consequences that ripple through the full ecological web. They have changed microbial populations, displaced fungi that promote tree root growth and remapped the home of millions of invertebrates and ground-nesting birds. A Hidden Legacy Of The Columbian Exchange From a biologist’s perspective, the European earthworms’ introduction illustrates the understated yet far-reaching implications of the Columbian Exchange. While most histories of the exchange revolve around plants, animals or disease, the shipment of subterranean fauna like worms shows how even the smallest of stowaways can steer the trajectory of ecological history. Columbus’s voyages did not only remake human societies; they triggered an intercontinental reorganization of life. Does the idea of an “invasive species” instantly change your mood? Take the Connectedness to Nature Scale to see where you stand on this unique personality dimension. Editorial StandardsReprints & Permissions