Copyright news

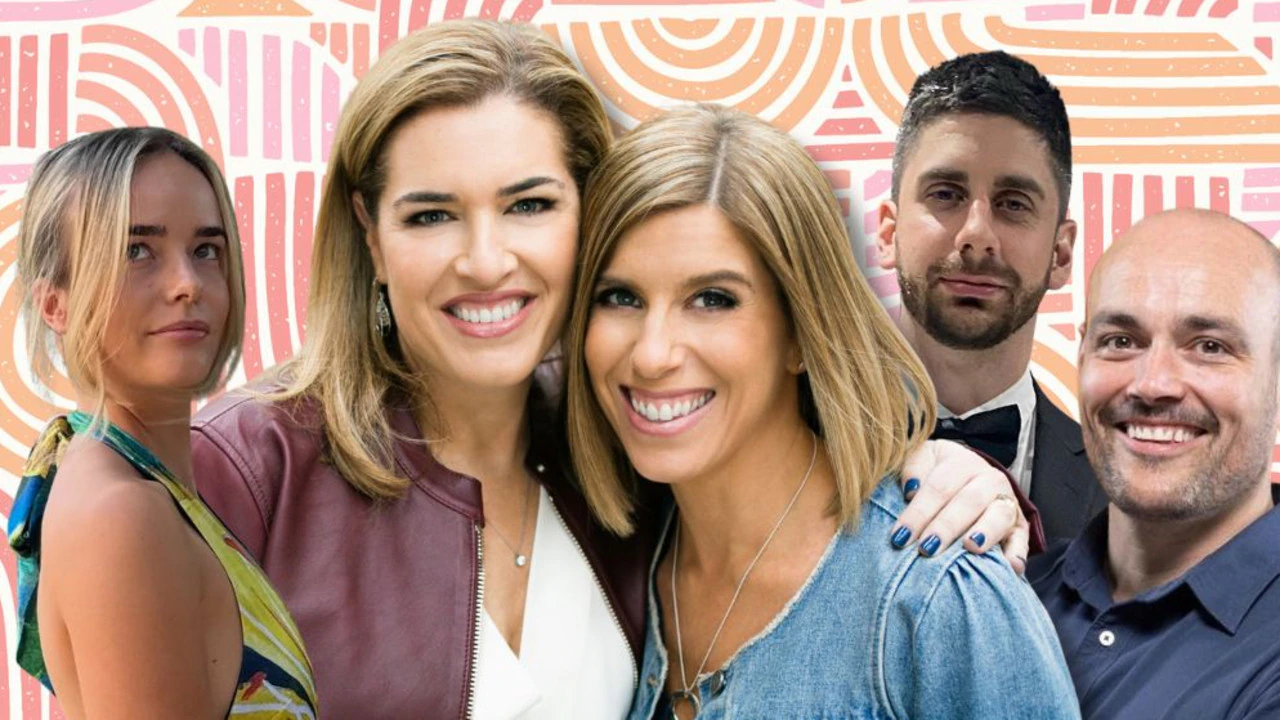

In the age of mass manufacturing and viral social media trends, local designers are competing with their own dupes – cheap overseas knock-offs of their original designs, often sold back to Aussies at a fraction of the cost. News Australia today launches the Back Australia campaign, an initiative that aims to champion local businesses, while exposing some of the threats that undermine them. From children’s lunch boxes to ergonomic desks, here are some of the brands grappling with the emotional, financial and creative toll of seeing their ideas stolen. The rise and replication of b.box For Melbourne entrepreneur Monique Filer, co-founder of b.box, the idea behind the brand was born out of necessity. “Having kids” was her inspiration, she told news.com.au, recalling the days she and her friend and co-founder Dannielle Michaels cut up cardboard in the kitchen to prototype their first product. It was called the nappy wallet, and it was conceived on a flight to New Zealand when Michaels struggled to change her baby. That was more than 15 years ago. Today, b.box’s children’s products – from colourful lunch boxes and sippy cups – are sold in more than 65 countries, and the company employs 70 staff. The brand’s success wasn’t inevitable but the result of a relentless drive to solve the many pain points that parents have – whether thinking about their own real-life problems or field-testing products with actual families. “We put a lot of thought into the issues we are trying to solve, whether it’s the usability from a child’s point of view, the ease of cleaning or the number of parts – that’s how our products stand out,” Ms Filer said. Unfortunately, with this kind of innovation came imitation. Ms Filer described the “flattering but frustrating” experience of seeing big global brands and manufacturers produce near-identical copies of their award-winning products. Their sippy cup, for example, has seen countless dupes hit supermarket shelves, often sold for much cheaper. Yet, she said, “every day of the week, we will outsell our competitors” – even when the knock-offs are on sale and b.box products are full price. She puts this down to the brand’s long-term commitment to quality, authenticity and safety. Cheaper dupes may look similar but often compromise on materials, design, functionality, and durability – elements that b.box meticulously tests. Of course, the brand aims to protect its intellectual property by taking legal action whenever possible and trying to “stop dupes at the source”, such as factories in China. But it’s an ongoing battle and, at the end of the day, “you can’t stop copycats”, Ms Filer said. And the time and money spent protecting IP could be better used to continue innovating. In the fight against dupes, the brand relies heavily on its reputation and ongoing connection with parents (many of whom are part of a nearly 160,000-person-strong, fan-run Facebook group). “Parents buy b.box products because they trust us and they know the quality and they understand what they’re paying for,” Ms Filer said. “You can copy a product, but you can’t replicate a brand. You can’t take that away from us.” Harvey Norman chief executie Katie Page agrees, telling news.com.au: “I think Aussies should support Aussie-made because it’s a quality product, you know where it comes from, it’s employing people and keeps communities happening. “We are not asking people to buy something for the sake of it – it’s still got to stand up to scrutiny and be value for money. “But I want Australians to understand you are going to pay a bit more for Australian made sometimes – but it comes through in the quality, you get what you pay for.” Fluicer’s gut punch For Alex Gransbury, founder of kitchenware brand Dreamfarm, the battle against copycats is also a constant struggle. His revolutionary citrus juicer, the Fluicer (a portmanteau of flat and juicer), mimics the way you naturally squeeze citrus with your hands, allowing you to extract more juice. It’s received international recognition, even appearing on Time Magazine’s Best Inventions of 2023 and Oprah’s Favourite Things list. Then came the blow. A major retailer launched an extremely similar “folding juicer”. “It felt like the air had escaped from my lungs,” Mr Gransbury told news.com.au about the moment he found out. “It was an absolute gut punch.” As a passionate designer, he was disturbed that the brand hadn’t even tried to improve upon the design, but had actually made it worse. In fact, the fake version, sold for a lot less, had such bad design flaws that Mr Gransbury said it wouldn’t fit an average-sized lemon. For Mr Gransbury, dupe culture seems like an unfair attack on the time and effort invested in creating innovative products. “This brand, or any of these other copycat brands, doesn’t have to do any research and development – they just steal someone else’s idea,” he said. “What they don’t understand is that for every 60 products we’ve developed, there are hundreds of prototypes that didn’t work, that never made it off the ground.” Despite some legal wins, Mr Gransbury called litigation “a costly road”, recalling one case that cost him $30,000 to recoup just $8000. “Why bother?” he asks. Like Ms Filer, he believes that money is better spent developing the next idea. “Ultimately, those who truly value design will always be our customers. They want the latest innovations as soon as they are available and they won’t wait for cheap knock-offs.” Sustainable designs ripped off for fast fashion Fashion is another prime example of an industry flooded with dupes, led by budget fast-fashion brands that rip off high-end designs. It’s a vicious cycle driven by social media platforms like TikTok, where younger generations, — eager to jump on trends but reluctant to spend — display their “dupe hauls” like a badge of honour. To date, the hashtag #dupe has more than 5.6 billion views on the platform. Melbourne fashion designer and sustainability advocate Cait Erskine found herself grappling with this issue after her brand Odysseus & Penelope went viral on the video-sharing app. The label, known for its bold, original designs featuring Erskine’s mother’s artwork, was thrust into the limelight after a slew of influencers started wearing its pieces and it quickly became a go-to “it girl” brand. Then, a blatant copy of its signature “Island Girl” top appeared on the Chinese e-commerce website Shein for under $5. The product listing allegedly even used her brand’s original photos. “They are shameless,” the 25-year-old said. “The top had a lot of reviews, so people are obviously buying it.” After news.com.au reached out, Shein removed the product and said it takes all infringement claims seriously. The company said it works with supplier partners, who are required to certify that their products do not infringe third-party IP. “We continue to invest in and improve our product review process,” a spokesperson said. Still, damage has been done, as the temptation to buy cheap foreign knock-offs often outweighs loyalty to local designers – especially amid the cost-of-living crisis. “We just hope people can still support our small business in some way, even if they don’t buy something. Just following our pages can really make a difference,” Ms Erskine said. Desky dupes John Beaver is yet another Aussie business owner who has been impacted by the rise of counterfeit products. He’s the founder of Desky, a brand that sells ergonomic desks for offices, work-from-home setups and gaming, but says the internet is now full of fakes. “I have spent over a decade in product design and retail, and I have seen the confusion that dupe culture creates for customers and the damage it does to honest local retailers,” Ms Beaver said. “We hear stories of people who purchased products they believed to be ours, only to discover subpar parts or unsteady frames.” Aside from lost revenue, he said these fakes erode trust in the “made in Australia” label. “We invest money to test, design, and source quality materials, so it is disheartening to see poor imitations labelled as ours,” he said. To fight back, Mr Desky has published detailed product specifications, testing data, and supplier information on its website, so customers can verify authenticity. “We also work closely with our Australian suppliers to make production limited and harder to copy. Progress is slow, but awareness is growing,” he said. Why is dupe culture so hard to stop? According to the Australian Design Council’s executive director Sam Bucolo protecting a product – and its look – is hard. “You can just change something slightly, and then you can copy it,” Mr Bucolo told news.com.au. Sectors with “low barriers to manufacturing,” like homewares, children’s goods or fashion, are hit the hardest, whereas highly complex, high-value-added products, such as medical devices, are much more difficult. And the fallout can be huge, especially for small businesses that invest heavily to attract top talent and designers. “These firms want to do the right things and employ good designers who make products that are actually ergonomic, or that meet a need and have good materiality – and all of this is lost when a bigger brand just copies a product,” Mr Bucolo said. “You can’t capture the value of what you’ve created when someone else reaps the benefits.” Consumers also suffer consequences, often ending up with inferior designs that look similar, but won’t have the same quality, function or safety. Mr Bucolo said the answer lies not just in tighter IP laws but in education. “We need a bit of a push for people to understand what makes good design. And when you buy an Australian-designed and made product, you’re buying all the knowledge, the testing and the social and cultural values behind it,” he said. “It’s critical to support local. We have this world-class design capability, and some companies are creating world-class products that punch well above their weight, and we need to make sure they get rewarded.” This article is part of the Back Australia series, which was supported by Australian Made Campaign, Harvey Norman, Westpac, Bunnings, Coles, TechnologyOne, REA Group, Cadbury, R.M.Williams, Qantas, Vodafone and BHP.