Copyright Newsweek

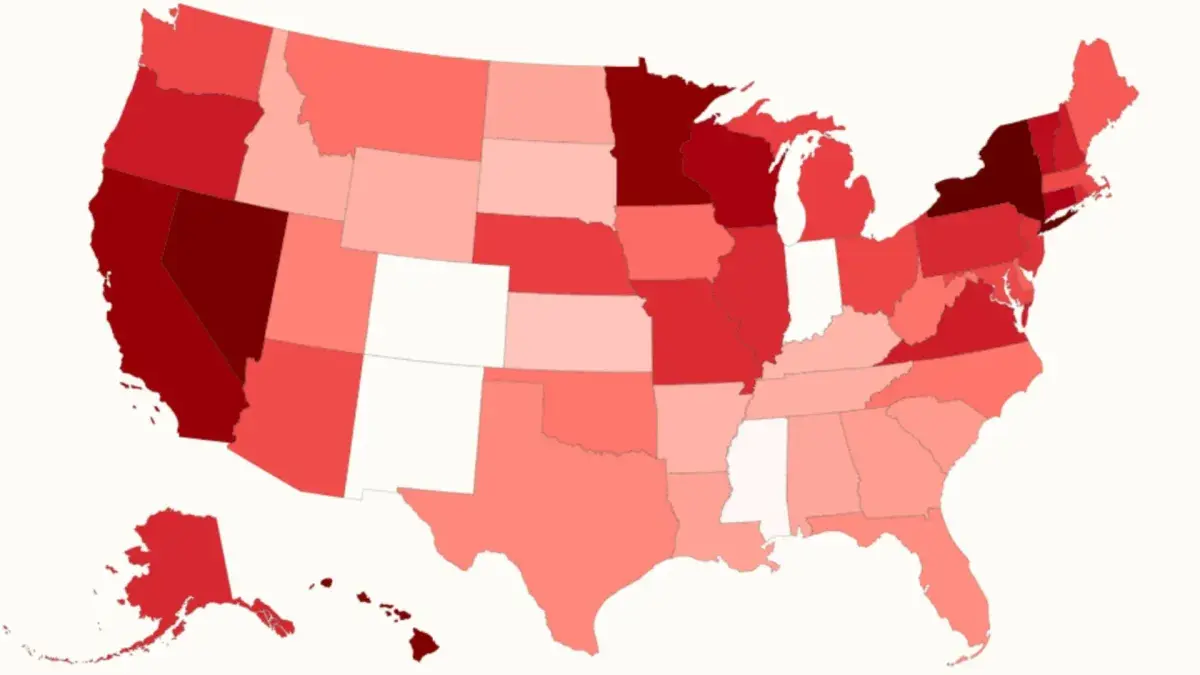

Massachusetts is the state with the highest child care costs in the country, according to new data from the North Carolina law office DeMayo Law. The new data highlights which states have some of the highest and lowest child care costs nationwide, and how much of Americans' income in those states is contributed to center-based care. Why It Matters The affordability of child care is a growing issue confronting Americans, and can be a factor that causes some to push back having children. Child care is considered affordable if it costs no more than 7 percent of a household's income, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, but many families pay far more than this benchmark, as the DeMayo Law data shows. The costs for looking after a child are also increasing rapidly in the country, as data from the U.S. Department of Labor showed that U.S. families typically spent between 8.9 and 16 percent of their household income for the care of one child, while the DeMayo Law findings found in some states, child care costs can be around double that range. What To Know As shown in the map above, Massachusetts, New York and Nevada ranked as the top three states for having the nation's highest child care costs, based on the DeMayo Law rankings. The average annual cost for child care in Massachusetts is $18,380, while the median annual income is $60,690, and infants in Massachusetts cost the most in the country with parents paying an average of $23,191 annually, which is 38.21 percent of the state's median income. The average percentage of income spent on center-based child care in the state was therefore 30.29 percent, while in New York it was 30.12 percent and 29.25 percent in Nevada. Other states with high child care costs included Hawaii, Minnesota, California, Wisconsin, Connecticut, Vermont, and Oregon. Mississippi was the most affordable state—with families spending just 12.36 percent of their income on average for center-based care. Kansas (16.03 percent), South Dakota (16.29 percent), Kentucky (16.95 percent), and Arkansas (17.16 percent) also offer comparatively lower child care costs. This means that Americans raising a family in Massachusetts can expect to spend over four times as much as they would somewhere like Mississippi, DeMayo Law said in its report. In Mississippi, families spend an average annual cost of $4,636 on center-based care, with a median income is $37,500. Explaining the possible reasons for these differences, Mildred Warner, a professor of city and regional planning, and global development at Cornell University, told Newsweek that higher costs typically happen in states that have higher costs of living in general, as well in states with "higher quality standards." She also said that costs of child care also vary by type of care. "Center-based care is the most expensive; family and group family care are less costly," she said. Broadly, child care cost is driven by wages, rent, supplies, and other things, like any business, Warner said, adding that these costs all rise "with inflationary pressures." "Early education teachers need to be recruited from the larger labor force—so comparative options in related occupations puts pressure on child care wages," she said. "Also, costs of everything—food, toys, utilities, rent—are rising, and that will force up child care prices too. But parents have limited ability to pay, and this is why public subsidies are so important." Due to an insufficient amount of data, Colorado, Indiana, New Mexico, and the District of Columbia were not included in DeMayo Law's rankings. In order to calculate its rankings, DeMayo Law used data from the National Database of Childcare Prices (NDCP) for center-based child care costs, and 2023 data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) for median annual income data per state. The percentage of income spent on center-based child care was calculated by dividing the average cost by the median annual income for each state. What People Are Saying David Blau, a labor and population economist at Ohio State University, told Newsweek: "The wage rate of child care workers is the single most important determinant of the cost of child care, because it is a labor-intensive sector. High-wage states such as Massachusetts and New York have high child care wages as well, and conversely for low-wage states such as Missouri and South Dakota." Mildred Warner, a professor of city and regional planning, and global development at Cornell University, told Newsweek: "The U.S. fully subsidizes education from kindergarten to grade 12, but not early education. Most of the early education (birth to five) is paid by parents—even though early education is most critical for brain development. Most countries around the world provide public school from age 3, and large subsidies for 0 to age 3 early care and education. The U.S. needs to do more, as early care and education is critical—for child development, for parents to be able to work, and for our society’s future." Louise Stoney, co-founder of Opportunities Exchange and the Alliance for Early Childhood Finance, told Newsweek: "Schools often think of child care as a 'cash cow' versus an extension of their mission. They often charge rent to operators that are providing care on school sites, rather than making space available for free, or keep a portion of any [Early Care and Education (ECE)] funding for administration versus sharing every available dollar with affiliated child care programs. In other words, even schools typically fail to support services for children 0 to 3 as a public good." She added: "The health insurance crisis is very serious for child care. The [Affordable Care Act] is the only way we have been able to help these teachers get benefits—and now that is collapsing as well." Taryn Morrissey, a professor and chair of the Department of Public Administration and Policy at American University, told Newsweek: "The biggest expense in child care is labor. We know in general that average wages and benefits in the early childhood sector are low relative to average educational attainment and training, and low wages and benefits fuels staff turnover, which is problematic for staff and children in care. "If wages were higher, costs would be higher; the early childhood workforce essentially subsidizes the costs of child care with low wages and few benefits. That is, the costs of child care should actually be higher, but parents with young children are typically at the lowest earning years of their careers and cannot afford more, which makes public financing (more like K-12 education) important. New Mexico is an example of a state that is dramatically increasing its support of child care."