Copyright Newsweek

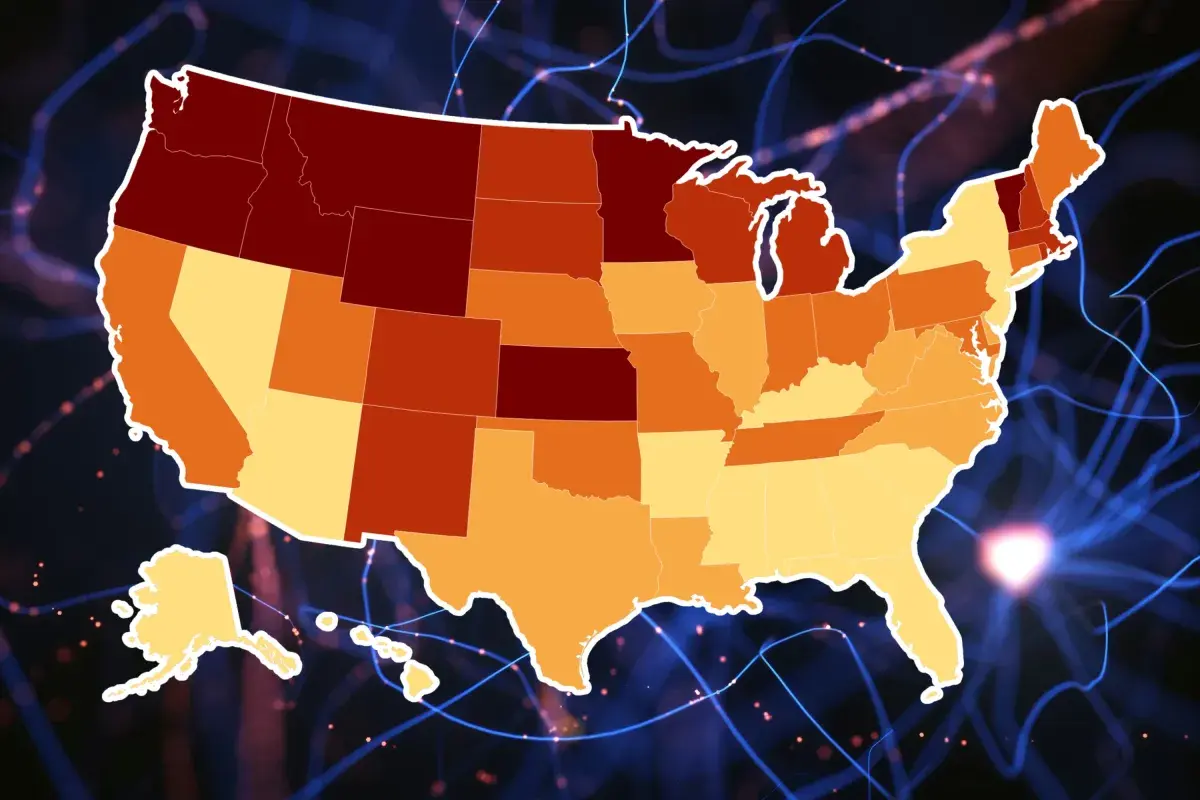

People in certain states in America appear to be more likely than others to develop devastating neurological diseases, a new study has indicated. Lou Gehrig's disease—also known as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS)—and Multiple Sclerosis (MS) both develop in people across gender, race, wealth and levels of access to healthcare. However, a new study has revealed that geography—where in the U.S. a person lives—has an extremely high association with the likelihood of developing the diseases. ALS is a neurodegenerative condition that affects how nerve cells communicate with muscles that eventually leads to muscles wasting away. There is no cure. An estimated 5,000 people in the US receive an ALS diagnosis every year, according to the Cleveland Clinic. MS, meanwhile, damages the protective cover around the nervous, causing muscle weakness, vision changes, numbness and memory issues. There is no cure, but treatment can help to manage the symptoms. Research had previously indicated that diagnoses of both ALS and MS are more prevalent in the north of the country, with those in the likes of Florida and Hawaii far less likely to be diagnosed than those in, for example, Washington or Minnesota. However, treatment with UV light or vitamin D to mimic the benefits of living in such a sunnier climate has not yielded significant results that might account for this differential. A new study published in Scientific Reports now shows a link between the two diseases when it comes to specific states, despite previous studies have generally concluded there was no evidence of a "mechanistic or genetic link" between ALS and MS. This relationship had possibly overlooked because of what is known as a Simpson's Paradox: a statistical phenomenon where a trend appears in different data groups, but not when the groups are combined. In the study—led by Melissa Schilling of New York University's Stern School of Business—when considered seperately, men and women showed a strong positive correlation in the geographic distribution of ALS and MS—but when the data was pooled across both sexes, the relationship was obscured because of how ALS is more common in men and MS more common in women. Schilling said in a statement that she was "surprised to find such a strong geographic pattern, as most of the research on ALS does not emphasize the role of geography. I was even more surprised to find that ALS has a very strong association with the geography of MS." She told Newsweek: "The results of this study indicate that whether we look as U.S. data from the CDC, or global data from the World Health Organization, there is a very strong positive correlation in the geographic distribution of ALS and MS, even after controlling for race, latitude, wealth, and access to neurological healthcare. "The pattern in the results points to the likelihood that the two diseases share an environmental trigger, and that opens up some exciting possibilities for future research." A heat map showing the geographic patterns of ALS in the United States shows its prevalence in states across the north, west, east and south, using metrics of deaths from the disease per 100,000 people, using age-adjusted data. It found that those in Hawaii and Alaska both had among the lowest rates, despite Alaska being in the extreme northwestern corner of the North American continent, and Hawaii located thousands of miles south of the US mainland. Schilling said in a statement: “This finding is important because it suggests that an environmental factor likely plays a significant role in both diseases, and that could provide clues that help us determine what causes them and how they might be avoided or treated.” These environmental factors could be anything from viruses and molds, or human practices like the use of heating oil or chemical contamination. Schilling noted that the "list of suspects is long," but there are ways to "significantly narrow the hunt"—such as in the Faroe Islands, where diagnoses of MS increased after military troops arrived in the 1940s. She told Newsweek: "Neither of these diseases is well understood from a causal point of view. We understand the pathology, but the underlying triggers that set this pathology in motion have been a mystery. This geographic association between the diseases should help us identify a set of potential environmental triggers. "I'm hoping to work with a consortium of scientists from a wide range of disciplines to start tackling these factors, one by one, to see which ones we can and cannot exclude as suspects." Do you have a tip on a health story that Newsweek should be covering? Do you have a question about ALS? Let us know via health@newsweek.com. Reference