Copyright Deadline

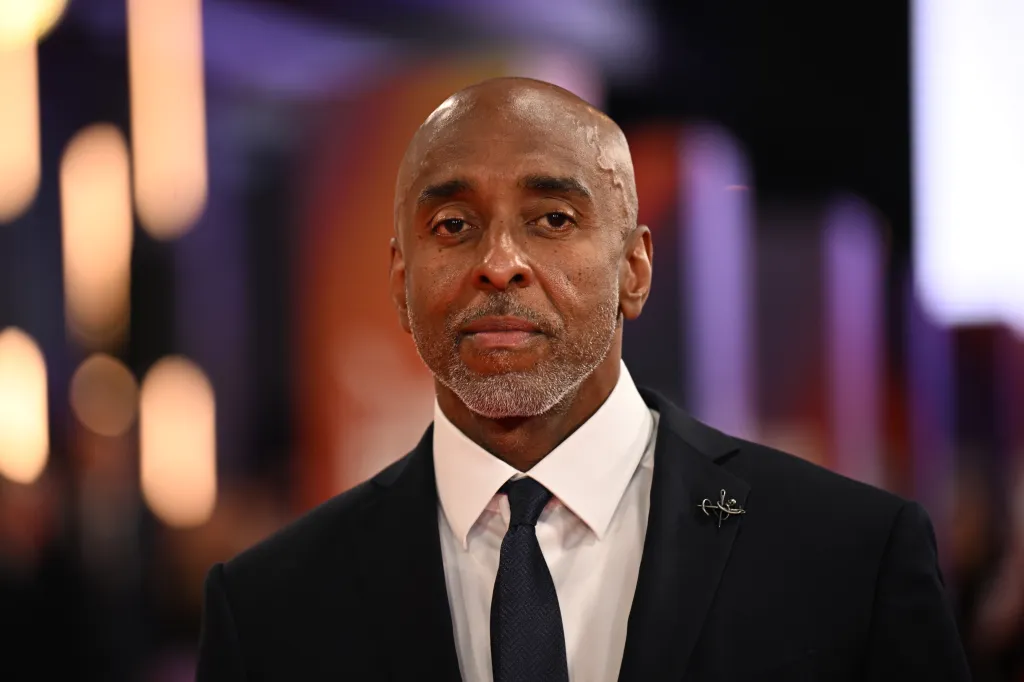

Across his decades-long career, filmmaker Malik Hassan Sayeed has sat for only a handful of feature interviews, which is unrepresentative of both his unique ability to communicate and his openness to sharing stories from his life. Indeed, when I meet Sayeed, we’re in London, where he has chosen a quiet restaurant away from the stuffiness of traditional industry hotspots, and we speak, over herbal tea, for multiple hours. Sayeed is in town for the London Film Festival, where After The Hunt, his latest feature as a cinematographer, is screening for general audiences and awards voters. A crafty and complex drama with an A-list ensemble, After The Hunt is the exact kind of work we have come to expect from the film’s director, Luca Guadagnino. The project also marks Guadagnino’s third feature in two years. But After The Hunt is a return to the mainstream for Sayeed, marking the first fiction feature he has shot since Belly (1998), directed by Hype Williams. Beyond his work as a cinematographer with Williams, which has been well-documented (if you’re unaware, the pair shot many of the most memorable music videos of the 1990s and 2000s, cultivating a visual language that dominated airwaves and has influenced everything since), Sayeed has shot films with Spike Lee and Michael Jackson, directed Prince, and began his career on the second unit of Stanley Kubrick’s Eyes Wide Shut. Below, the veteran filmmaker speaks with us in depth about his eclectic career, why he took a two-decade-long hiatus from fiction films, and why Guadagnino was the director who brought him back. The pair have already finished their second collaboration, the Sam Altman feature Artificial. Sayeed also shares memories from his experience working on music videos with legendary artists like Prince and how he approached shooting After The Hunt, which is set in Connecticut, while filming entirely in the UK. Deadline: Malik, you don’t do many interviews. Why? You’ve had such a unique career. MALIK HASSAN SAYEED: I’ve had terrible experiences. When I did Eyes Wide Shut, I interviewed with Entertainment magazine. They did a piece with me because both Eyes Wide Shut and Belly were coming out the same year. At the time, with Stanley Kubrick, they wanted to make him look like the crazy guy. So when I did the interview, they took my words and contextualized them around him being crazy, when what I really said was that he’s a meticulous artist. I was praying that he wouldn’t see it, but he did. He was irate, and I was devastated. I handwrote him a multi-page letter just explaining how much he meant to me and how my words had been taken out of context. He was extremely appreciative, and the only thing he said to me was, ‘This is why I don’t do interviews.’ That was triggering and made me realize the importance of owning my words. Deadline: I can imagine. People forget how Stanley was spoken about when he was alive. SAYEED: And then it happened again when Melina Matsoukas’s film, Queen and Slim, came out. The New Yorker was hitting me up, and I was just ghosting them. But Melina asked me to speak with them, so I did, even though I was hesitant. They did the same thing. They took my words out of context again to make it seem like I said Beyoncé was controlling. This was around Lemonade. So, my thing is, you can’t mess my words up if they don’t have them. Deadline: After The Hunt is your first fiction feature since Belly (1998). I was born in ‘97, but that film was still so important for my generation. Why did you step away for so long? What were you doing? SAYEED: I had a kid. I’m not a good multitasker. I need to focus on one thing at a time, so I sort of stopped working to focus on raising my family. I was also working a lot, directing commercials, which has its own demands that you need to develop. It requires its own kind of focus, so overall, it was beneficial for me to do these short-form projects because they’re in and out, while other work can take time. I once did a pilot with Spike… Deadline: The HBO show? SAYEED: Yes, the HBO show with John Boyega. It never came out. The producer was Doug Ellin. Traditionally, if HBO is doing a pilot, they’re committing to the show. Ellin had three shows with them, ours, one with Michael Rapaport, and another. They all got killed. We had John Ridley writing and producing, with John Boyega starring, and Spike directing. So I was away from home for a while working on that. When I got home, it was interesting to see how my daughter reacted. She had put up some boundaries. At that point, I was more deliberate about being precise about the work I did. It had to be worthwhile, and simply nothing presented itself as worthwhile. There had been some things that came, but the synergy also has to be right. Deadline: When I heard you were working with Luca, I thought that was so random. But then I remembered hearing him speak passionately about his admiration for the great Haile Gerima, whom you studied under at Howard Film School. SAYEED: Yeah, Luca is super sharp and smart. He has very good taste and broad interests, which are really aligned with my own. If you just look at the cinematographers he’s worked with, you have Sayombhu Mukdeeprom, Arseni Khachaturan, and Yorick Le Saux, who works with Olivier Assayas. He’s making precise choices. So actually, by the time he got to meet, I thought, ‘Wow, this is a bespoke list that I’m excited to be a part of.’ Deadline: The film is set at Yale, but you shot at Cambridge University in the UK, right? SAYEED: We shot the whole movie in the UK. It was a six-week shoot. We shot one week at Cambridge, and then the rest was shot on stage at Shepperton. Deadline: How did you go about recreating New Haven in England? SAYEED: It’s all craftsmanship. That’s the great thing about years of experience. There are some interiors in the film with exterior light. And some day exteriors. The day exteriors are the quad and the Tandoor New Haven restaurant. We replicated the Tandoor restaurant. We built the whole thing on the studio backlog. I went to the actual restaurant. I spent hours in there, like I did with many of the real locations in the film, with my camera, studying the environment. The film is also set in two time periods. There’s 2019 and then the present day. 2019 is a Spring setting, and the present day is Winter with snow. The thing about England is that the weather changes on a dime, so we had to manage that with big construction cranes. Deadline: The film’s opening shot. It’s brilliant. When I was watching, I thought that had to be Malik. It’s when Ayo’s character is looking at the African statue in Julia Roberts’ home. It sets the story up perfectly without saying a word. SAYEED: That’s all Luca. He didn’t mention that shot out loud, but when we set up, that’s where he put the camera. Now, what’s amazing about that is he dressed that space himself. He took a weekend and dressed the entire space, because it was critical for everything in the rooms to speak to who those people were, including that artifact. Luca had a backstory about Julia’s character, working on research in Africa at some point in her life. You also see that in the scene where her husband makes Ethiopian doro wat. When I first read the script, Ayo’s character was white. Her being Black was a layer Luca added. When casting started, Zendaya was going to play that part, a natural choice coming out of Challengers. And then Ayo was cast. Luca stays present in the moment. You can see it from that opening shot. It wasn’t originally in the script, but he stays engaged and alive as a filmmaker. Deadline: The house shared by Julia Roberts and Michael Stuhlbarg’s characters is lit so specifically. It’s all warm light from those funky lamps. It feels like a real affluent space. SAYEED: That was the motive. Everything had to feel like it was from the lamps. We had two standing lamps that we used, depending on the framing, because they produced a certain quality of light that is difficult to replicate with film lights. Then we layered that with other lights to create that naturalistic environment. That space represents a lot for the characters. Luca had a whole backstory about that space and how Frederick’s [Stuhlbarg] grandparents had come over to the U.S. from Europe to escape the Holocaust. He tracked that journey through several eras of the family, who worked to make sure their kids went to college. They became lawyers and doctors. And then we get to Frederick, the grandchild, who is now a psychotherapist. And then Julia comes and adds her own history to the house. Deadline: After over 20 years, was it tough getting back into the saddle for fiction filmmaking? SAYEED: The only thing was the rhythm. The best way to describe it is if you’re a sprinter, you don’t run marathons, but you’re still running. Everything is the same. You just adjust to the rhythm of your specific race. Whether you’re working on fiction or commercials, you’re still doing the same thing. You’re looking for the nugget of the scene, meaning the most important thing in the scene. When Hype [Williams] and I started doing music videos, we wanted to make the visuals look how the music made you feel. It had nothing to do with the lyrics. We got our 10,000 hours in doing that. We became proficient. My first experience was working on the lighting for the theater. On stage, you’re designing the light around the emotion of the scene. And it’s even more precise, because you only have lightning, you don’t have photography on the stage. Deadline: During my research, I saw that you worked with Prince. You directed the music video for The Greatest Romance Ever Sold, one of his most underrated songs. What was that like? SAYEED: Prince was amazing. It was his first song or video back since he adopted the symbol moniker. We still couldn’t call him Prince yet. I would just start talking to him without saying a name because we didn’t know what to call him. Deadline: Did you shoot After The Hunt on film? SAYEED: Yeah, we shot on film. Luca only shoots film. In fact, we worked on a commercial together where we had to fly a drone, and we still used a film camera. I just shot helicopter scenes for our new film with a film camera, and because there aren’t many apparatus like gimbals that can handle a film camera, the particular gimbal we used just came off the Christopher Nolan movie and was on its way to Dune, so we had to catch it in time. I hope that film is coming back enough for the business side to support the continued development and innovation of the medium. I know film is becoming increasingly popular with younger people. On the last four or five shoots I’ve been on, every time I’m on set, I see kids with the film cameras. They’re either shooting stills or Super 8. I pray that’s where we continue going. It’s funny, everybody’s worried about AI, but when humans are at their best, AI can’t touch us because AI has to feed off of something we’ve done. I’m more worried about the humans behind AI, blaming AI for some stuff they’ve done. If we accept mediocrity, yes, AI can recreate mediocrity, but when we reach greatness, AI can’t produce that. Deadline: Are you planning to work on more projects, or will you take another break? SAYEED: If I have another opportunity to be in a working space like After The Hunt, then yes. But you can just never predict that. Deadline: You have one project listed on your IMDb titled Compton’s Finest. What is that project?