Malcolm Jenkins always paid attention to detail. Now he’s using that eagle eye in photography.

Malcolm Jenkins was a two-time Super Bowl champion and three-time Pro Bowler, and this November he will be inducted into the Eagles Hall of Fame. He prided himself on playing any position defensive coordinator Jim Schwartz asked him to, whether it was slot corner, linebacker, or safety.

That versatility was seen as an asset, but only on the field. Still, football was never Jenkins’ entire identity. He had other hobbies — poetry and art, for example — and pursued them in his free time.

In college, that varied approach was met with skepticism by NFL scouts. It was a “knock” against him, something that traveled with his profile as he moved throughout the league.

“The rap on me was that I was a great leader, a phenomenal player, and had all of the skills,” Jenkins said. “The only question mark was if I was going to be coachable enough, because I was really smart. And that I had other interests off the field.

“It was like, ‘Are we going to be able to control this guy, essentially?’”

For a while, Jenkins tried to adhere to that code. He hid his passions. He stuck to football. But later in his career, he started to speak out about social issues. He shared more facets of his life, like his art collection, and began writing op-eds.

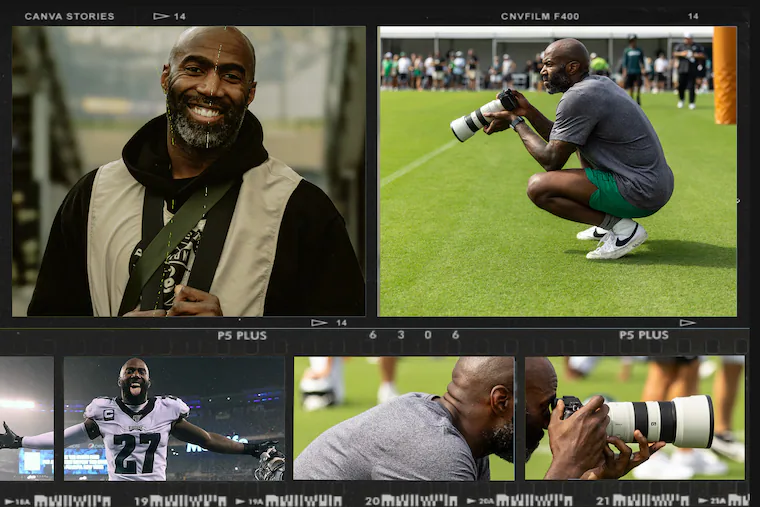

Now, in retirement, Jenkins is putting his versatility on full display. He runs a charity, The Malcolm Jenkins Foundation. He has a bourbon line. He collects art, writes a Substack, and owns a media company. This Sunday, Jenkins will be on the Eagles’ sideline, not as a player or coach, but as a photographer. The list of projects is a dizzying. But Jenkins is grateful for them all.

» READ MORE: For years, he was Phil and she was Phillis. Decades later, these former Phillies mascots are still best friends.

“I feel alive when I’m learning new things,” he said. “I’m really energized by it. It’s very comfortable for me, because that’s literally what football was. You play the game, you evaluate the game, you prepare for the next one. And it’s a different opponent every week.

“That’s really how I’m approaching life. What are these different areas? What am I afraid of? What do I need to work on? What’s my plan to do it, attack it, review it, keep going?”

Blending creativity and football

Jenkins has always been a voracious learner. He got this quality from his father, Lee, who encouraged his son not to assume anything; to always strive to understand the why.

It was a lesson that was reinforced throughout the former safety’s childhood in Piscataway, N.J. Even though he was on the “conveyer belt” of elite high school football, he was also exposed to a diverse array of activities.

His aunt, Cynthia Vaughn, was an artist. Her work adorned the walls of Jenkins’ childhood home, and over time, he grew to appreciate it. When he was at Piscataway High School, he took a creative writing class, and found that he gravitated to poetry, in particular.

One day, a teacher pulled him aside, and complimented him on his writing.

“I was really excited,” Jenkins said, “so I continued to do it.”

After Jenkins enrolled at Ohio State in 2005, he realized that others were skeptical of his non-football pursuits.

Early on, a public relations staffer asked if he had any fun facts to include in the media guide. He told them about his poetry.

It was shoehorned into a bullet point, but no one delved any deeper than that.

“I used to write poetry all the time, and people always saw it as a gimmick,” he said. “Kind of like, like ‘Oh, wow, you write poetry as well as playing football. That’s so cute.’”

Jenkins decided to keep his artistic side to himself, and continued to do so when he was selected by the Saints in the first round of the 2009 NFL Draft.

He debuted in a different media environment than there is today. Players didn’t have podcasts. They didn’t post photos of themselves walking into the stadium, to show off their sense of fashion.

If you had other interests, beyond football, you had to back it up on the field, or else it would be seen as a hindrance, Jenkins said. That included your personal life, too.

» READ MORE: Nick Sirianni was his mentor. Now, Roy-Al Edwards is building a new football program.

As a young Saints cornerback, Jenkins witnessed running back Reggie Bush getting hounded by the media about his relationship with Kim Kardashian. It served as a cautionary tale.

“There was a lot of hype around him,” Jenkins said. “And when you are doing things like that, the pressure is that you must perform and be almost the best at what you do.

“And if not, all of those things quickly get turned into distractions. ‘You’re not focused.’ You can have interests, but you better be damn good.”

Nevertheless, Jenkins knew that there were athletes who were able to balance both. Larry Fitzgerald was one of them. In July 2009, the then-Cardinals wide receiver invited the rookie defender to Minnesota to train with him before the upcoming NFL season.

He peppered Fitzgerald with questions about his fitness regimen, his diet, and his routine. But they also talked about his life off the field.

Fitzgerald collected art. He traveled the world during the NFL offseason, and captured his adventures through photography.

Jenkins was surprised to hear this. He couldn’t believe that a perennial Pro Bowler had the bandwidth to pay attention to anything outside of his sport.

“It made me look at my situation differently,” he said. “I’m like, ‘Hold on, here’s a guy who is at the top of his game, the peak of his career, and is still finding time for himself, for leisure, for exploration.

“How are you structuring your life so that you can effectively handle all of these different things? I was definitely inspired by him, and a few others, who were balancing a lot but weren’t necessarily broadcasting it.”

Marques Colston was another influence on Jenkins. He remembers flying on the team plane, returning to New Orleans from an away game, and seeing the Saints wide receiver on his laptop, poring over excel spreadsheets.

Colston later went on to launch his own investment firm, among other business enterprises.

“While [our teammates] were sleeping, he was working,” Jenkins said. “It was like, ‘OK, that’s what it takes to do more than everybody else.’”

Setting an example

As Jenkins built his football career, in New Orleans and Philadelphia, he always kept this duality in mind. But he wanted to make sure he was established enough, as a player, to fully pursue and share it.

That time finally came in 2016, when Jenkins was the midst of his third season with the Eagles. In August of that year, 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick took a knee while the national anthem was playing ahead of a preseason game, to protest police violence against Black Americans.

A few weeks later, Jenkins and three of his teammates joined in, raising their fists in a message of solidarity.

The safety only became more expressive after that. He co-founded the Players Coalition in 2017. One day, instead of taking questions in the locker room, he held up signs with messages about the inequities and injustices of American life.

“That was the catalyst to me using the public platform as my medium,” he said. “It was also the point of time in which I realized that storytelling is probably the most effective way to approach that change.”

Gradually, Jenkins began to share more about himself. He founded a media company, Listen Up Media, in 2018. After he retired, in 2022, he started collecting art and invested in a Philadelphia Millstone Spirits Group, with the intention of elevating whiskey sourced by Black and brown farmers.

» READ MORE: Ray Didinger wanted to retire but couldn’t stop working. Now he’s written another play.

In 2024, he dove into photography, and this year, he created a Substack. Jenkins knows these activities might seem disparate; random, even. But in his mind, they are all connected.

It’s about storytelling. About communicating possibility, not just to the next generation of athletes, but to underserved communities.

This is where his foundation comes in. Its premise is to educate kids on financial literacy, as well as other career pathways they could pursue, whether it be art, whiskey, poetry, or something entirely different.

“We want to expand where we promote value,” he said. “Because before it was, either you’re an athlete, or an entertainer, or a doctor, or a lawyer. And it’s like, if you’re not one of those things, then essentially you bring no value to the community.

“And I think that that narrative is a dated one. One that I’m not really trying to prove wrong through argument, but through example.”

‘What aren’t you doing?’

Last year, when Jenkins was on vacation with his kids, he brought his Canon camera, and began to shoot images he found compelling.

The practice was less about results, and more about self-exploration. He’d examine his photos after the fact, and would try to understand why he gravitated to certain subjects in the first place.

Buildings, for instance. He always loved photos of buildings, and never knew why, until a conversation with his father in March.

He learned that Lee Jenkins had once dreamed of being an architect. The father told his son that none of the white firms would hire him, so he became a software engineer, instead.

All of a sudden, Jenkins’ curiosity in towering structures made sense.

“I think a lot of times, we don’t have the time to just stop and self-scout,” he said. “And that’s a tool I learned playing football. You study yourself because you know the opponent is studying you. And now there is no opponent. It’s just me.

“I get to know myself a little bit better by just asking those questions. Where does this particular thing come from? And lo and behold, I find my dad’s old architecture plans.

“It’s not by happenstance. There’s an actual connection and a language here, a thread to pull on. And so those things are exciting. Because when you’re so singularly focused on just the game, you don’t develop the other parts of you.”

He immersed himself in photography this year, upgrading his camera to a Sony A1 Mark II, while closely studying YouTube tutorials.

Jenkins also began going out in the field. It started with a Union-Inter Miami game in May. Then, he photographed Jets and Eagles training camp in August, and the Saints-49ers game in New Orleans last Sunday.

» READ MORE: How Jalen Hurts’ favorite move since he was a kid has helped make him an elite running QB: ‘It’s a natural thing’

This Sunday, he’ll walk onto Lincoln Financial Field in a photographer’s vest, with a credential around his neck, as the Eagles take on the Los Angeles Rams.

“It’s to the point now where … I’m surprised that nobody’s surprised,” he said. “They’re caught off guard a little bit with the vest and stuff. But then it’s like, ‘You’re always trying something new. What aren’t you doing?’”

Jenkins has had opportunities to pursue other fields, like broadcasting, that are more typical of a retired NFL player. He might try that in the future. Or maybe he’ll try coaching.

But for now, he is content with where he is: learning a lot, and challenging himself every step of the way.

“I think it’s scary for me to not be challenged,” he said. “And that’s not to say that broadcasting or coaching wouldn’t be challenging. I just think that there are many avenues right now that aren’t good timing.

“Right now, I need to train every aspect of my vision, my ability to plan, my ability to convene people. All of those self-scout things. Then, if I do step into any of these other arenas, I’m able to do it in a way that is uniquely me. I can show up and be passionate, because I didn’t sacrifice any of that growth, for the comfort of doing something familiar.”