“Your learning curve is huge,” she added.

Three years later, Small now sits at the head of a thriving nonprofit called Reentry Sisters, which lobbies the Maine state legislature, sends groups of women to college, and holds highly-attended conferences advocating for incarcerated women.

This summer, the group received a $150,000 grant from the Sunshine Lady Foundation, a philanthropic organization that specializes in offering higher education for formerly incarcerated people, according to their website.

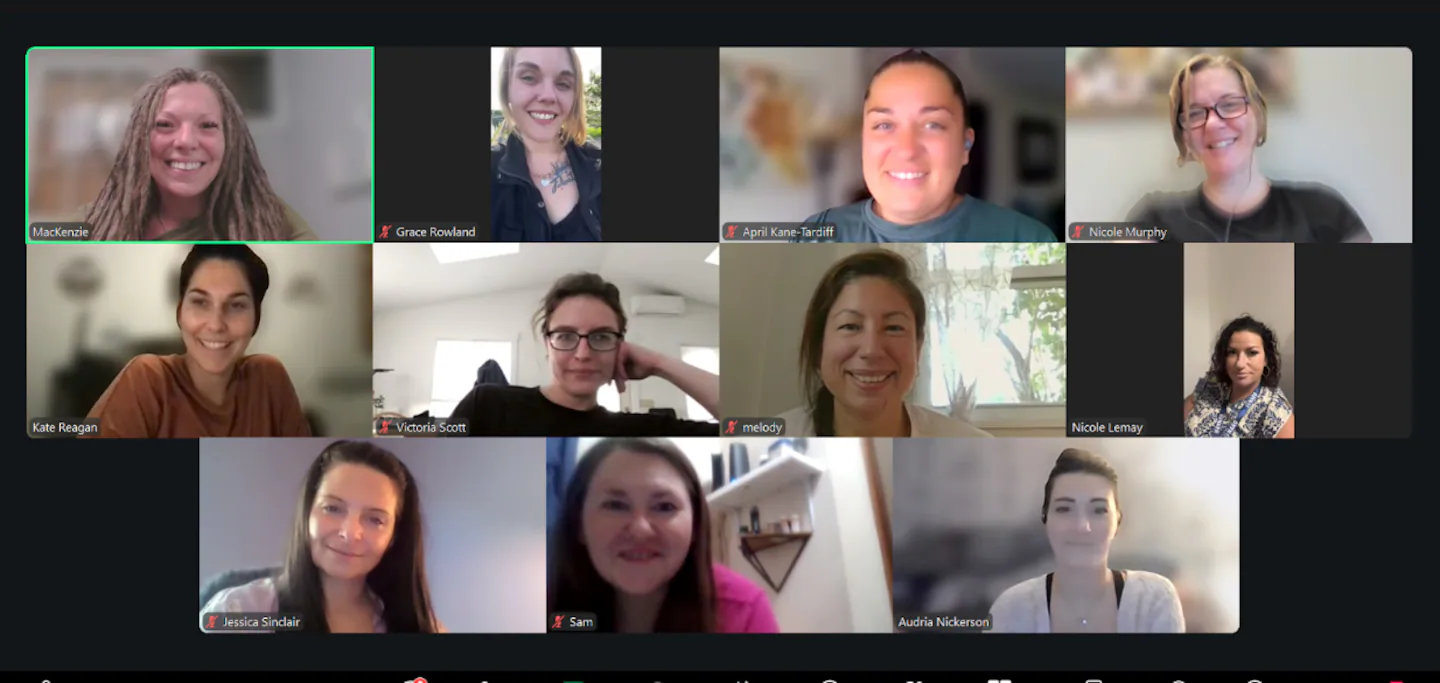

That grant allowed Small to send a cohort of nine women in Reentry Sisters to Colby College this semester, a move that one member of the cohort called a “blessing.”

“I feel supported for really the first time in my life,” Nicole Murthy, 41, said in a phone interview. “Nothing really compares to just the support and love that comes from this organization and this group of women.”

Women in the group have served time for drug offenses, assault, and other charges. All of them are dedicated to turning their lives around, with the help of Reentry Sisters, Small said.

“Getting a degree from Colby is definitely going to be a leg up for me and for my future,” April Tardiff, 40, said in a phone interview.

The group’s focus on education has a personal angle for Small, who earned a bachelor’s degree in history and liberal studies while incarcerated, and upon release managed to get hired part time while living with a sibling.

But she still found herself missing the women she served time with, whom she called her “surrogate family.”

“[They’re] the ones who you have this shared experience with, the ones who understand what you’re talking about, the one’s who hold you in non-judgement,” she said. “If you need help at two o’clock in the morning, they’re gonna take your call.”

She also knew that, as someone with a stable house, a job, and an education, she was in a position of privilege not afforded to many women coming out of prison.

“Many women come out and they go to homeless shelters, they live in a car,” she said. “They choose between homelessness or an abusive situation that drove them into the system in the first place.”

So she sent a Facebook message to MacKenzie Kelley, her friend on the inside who was released six months before she was.

Together, the pair started a Facebook group for women they knew from prison.

“I would post job opportunities on there, educational opportunities,” Small said. “It’s everything from those types of things to somebody posting on there ‘hey, I’m in such and such a town, my car broke down, I need a ride to the grocery store.’”

“We’re the only organization in Maine taking care of justice-impacted women, and we’re one of the few in the country,” Small added. “We are your family, we want to catch you when you come out of prison.”

According to a 2018 study published in the National Library of Medicine, 59.5 percent of incarcerated women in America have less than a high school education, compared with about 44 percent in the general population.

“Education opens up the whole world to you,” Small said. “It changes the way you view yourself, the way you see others, your place in the world.”

Small was a recipient of Maine’s Department of Corrections college programming system, but, she said, the program is “very limited” for women inmates, with only 1 percent of incarcerated people in Maine taking college classes.

The women started taking classes at Colby on Sep. 4, Small said.

“Colby College is partnering with Reentry Sisters to build an innovative model of education-based reentry support,” a Colby College spokesperson said in a statement. “It is designed to offer sustained, meaningful, and effective assistance for successful reentry after incarceration.”

Members of the cohort expressed excitement and gratefulness for the opportunity to take college classes.

“In one semester, I took English, algebra, biology, and history,” Tardiff said. “I’m going back and reliving what I didn’t get to experience.”

“I’m thrilled with it. I’m honestly thrilled with it,” she added.