Just hours before an executioner pushed vecuromion bromide and potassium chloride into the veins of convicted killer George Kent Wallace, Robert Hill scrambled to find a phone number for the penitentiary warden.

He had a message for the death row inmate.

“I felt commanded by God to do it. I asked them to tell him that I forgave him for what he did to me,’’ said Hill, 64, who at age 15 escaped after Wallace beat him in the back of the head with a claw hammer on May 29, 1976, in downtown Winston-Salem.

Wallace’s modus operandi, paddling young men with a wooden board or dowel, led law enforcement to dub him “The Mad Paddler.”

The Winston-Salem truck driver’s paddle featured the words “Board of Correction,’’ the phrase “A child should never be punished without a definite END in view,” a cartoon image of a little boy and girl, bent over as if to receive a paddling, and the words, “Victims sign here.’’

No victim ever signed the weapon, though, police said.

Wallace would masquerade as a police officer with a fake badge, handcuffs and leg irons. Later, as his violent behavior escalated, he would brandish knives, hammers and guns, according to Allen Gentry, a former detective for the Forsyth County Sheriff’s Office who worked the case for nearly a quarter-century.

This year marks 25 years since Wallace’s Aug. 10, 2000, execution at the Oklahoma State Penitentiary for the murders of two teenage Arkansas boys he had killed over the state line in Oklahoma.

But Wallace’s crime spree began in the Triad in 1966, when he was 25 and convicted of assaulting five young boys in High Point.

Wallace was never convicted of, but ultimately confessed to killing two Forsyth County teens — Jeffrey Lee Foster, 14, in 1976, and Thomas Stewart Reed, 18, in 1982.

He would go on to commit crimes in Arkansas and kill in Oklahoma where he was sentenced to die.

But because he was a long-haul truck driver — a transient worker with routes across the nation — investigators will never truly know the extent of Wallace’s crimes, said Gentry.

Now, the spotlight is back on Wallace’s crimes as Emmy-winning filmmaker Devon Parker of Arkansas wraps up an documentary series about the serial killer and his victims. The series features victim Hill and Gentry.

Single, Wallace lived with his parents in their modest Winston-Salem home at 3799 Sandalwood Drive in Old Town during the 60s and 70s.

He made a habit of driving his father’s cars when he committed crimes. First, a blue 1962 Pontiac Tempest, and later a light blue 1974 Plymouth Valiant.

Outside of the Triad, he rented vehicles when he cruised for his prey, said Gentry, who came to know Wallace well, interviewing him about his crimes for more than a quarter-century.

Wallace would move in and out of North Carolina jails for some 30 years, returning to crimes against young men every time he was freed and revving up his sadistic behavior, said Gentry.

Despite his violent crimes, Wallace managed to be released from prison early at least four different times. In fact, Wallace targeted Hill just four months after his release from prison in February 1976 after serving only 10 years of his 15-year sentence for the 1966 High Point kidnapping and assault crimes.

Robert Hill

It’s been 49 years since Hill’s nightmare began.

“It’s May 29, 1976. I’m 15 years old. Rock ‘n roll is my thing, and I was with my older brother James, who played guitar, and we were so excited,’’ Hill said of the Southern rock concert he attended that day at Groves Stadium in Winston-Salem.

“You could feel the electricity in the air.’’

Lynyrd Skynyrd, ZZ Top, Point Blank and Elvin Bishop were performing at the day-long event that kicked off around 2 p.m.

Hill, an eighth-grader at Mineral Springs Junior High School, was proud to ride along to the concert with his “cool’’ brother and his brother’s girlfriend. And Hill was looking forward to his last summer before starting high school, he said.

“It was raining on and off that day,’’ said Hill, a retired emergency medical technician and nurse who grew up in Winston-Salem and now lives in Jacksonville, N.C. “I remember I wore a clear raincoat,’’ he said with a chuckle.

Bands played through the rain and Hill met up with school chums and became separated from his brother and his girlfriend. By about 9:30 p.m., “I was tired, and I was getting hungry,’’ he said. “So I went back looking for my brother, and they had left me.’’

His home was only about three miles away on Elm Street, off Cherry Street, but bad weather and exhaustion made Hill decide to hitchhike, he said.

“It was nothing to do that in the ‘70s. I had hitchhiked a few times. Never had any trouble. Plus, you’re 15 and you think you’re bullet proof,’’ he said.

“I was not high. I was not drinking. I was not doing drugs,’’ Hill said. “I was clean and straight and I just got kind of tired, so I climbed over the back fence of the stadium to Baity Street.’’

From there, he walked to what is now University Parkway “and it started to rain kinda hard, so I just stuck my thumb out,’’ Hill said.

A light blue 1974 Plymouth Valiant driven by Wallace and pulled over right away.

“I got in and asked the man, ‘How far are you going?’ And he said: ‘It doesn’t matter.’ It was the tone of his voice when he said that that put me on my guard,’’ Hill said.

“So I sat with my back halfway against the passenger door. I’m looking at him and I’m studying him. He put me on alert. I knew something’s not right here.’’

Wallace drove toward Forsyth Correctional Center, made a lane change and traveled a bit farther.

“There was an armrest,’’ Hill said of the front seat. “(Wallace) kept his right hand down by the armrest like he kept something there. He was out patrolling, and he was going to get somebody that night.’’

Worried, Hill told Wallace to pull over. When Wallace did, Hill let his guard down and turned his gaze from Wallace to reach the door handle, he said. “(Wallace) put it in park, reached behind me, pushed the lock down, grabbed me by the back of the neck and forced my head almost to the floorboard.’’

Wallace demanded Hill place his hands behind his back, but Hill refused, he said.

“Very quickly, I got hit by the first blow of the hammer to the back of my head. After that first blow, I saw a bright flash, but I didn’t feel pain,’’ Hill said.

“I did feel the impact and the following five blows seemed like very quiet thuds,’’ Hill said. “After the sixth blow, by the will of God, I yanked up out of that floorboard, knocked him against his door and knocked the hammer out of his hand.’’

The hammer bounced across the backseat, Hill said.

“We locked eyes and his eyes were solid black, just like a demon,’’ Hill said.

“He did not have his weapon. And that is when I saw the fear of God in someone. It scared him so bad, he reached past me, popped the lock, hit the door handle, and pushed me out,’’ Hill said. “I hit the ground running.’’

Stunned by the blows, “I couldn’t speak. I just threw my arms up waving around the intersection of Cherry Street and Retnuh Drive,’’ Hill said.

A woman driver saw him bloody and disheveled and sped away. Then Hill noticed Wallace backing up as if to run him over.

Hill darted across the street into his neighborhood and straight to the door of a school acquaintance, Mona Weatherman.

“I’m numb and I’m banging on the door, and I was finally able to speak enough to say, ‘Is Mona home?’’’

Mona’s parents pulled Hill into the house and tried to stanch the bleeding from his head wounds with towels while he gathered himself in their kitchen.

Their two sons took off to try and find Hill’s attacker or the weapon, but to no avail.

The Weathermans called Hill’s parents, the late Jim and Carol Hill, who took their teen straight to Forsyth County Hospital emergency room. Longtime Winston-Salem surgeon, the late Pete Parker, was on duty that night and treated Hill, he said.

“I had one place at the base of the skull. I heard them refer to the place as the ‘death blow.’ My scalp was gone in two places, and I had three more huge lumps,’’ Hill said. “I remember I refused to lay down on the gurney. I was afraid that if I laid down, I would die.’’

Remarkably, Hill had no skull fractures, but did sustain a severe concussion from which it would take months to recover.

The hospital sent a rattled Hill home that night to recover with close monitoring by his parents.

Afraid to sleep in his basement bedroom, Hill bunked on the upstairs sofa.

He asked for his clock radio.

Hill says, “If you know me, you know that when something bad happens to me, something funny always happens, as well.’’

The first song that played on 107.5 FM as Hill tried to sleep: “Peter, Paul and Mary, singing, ‘If I Had a Hammer (The Hammer Song),’’’ Hill said, laughing. “God said, ‘You’ve made it through. Have a laugh.’ I changed the station.’’

But Hill couldn’t turn off the thoughts of Wallace returning to kill him.

“Everywhere I went, I was looking for that car, that face,’’ he said of his captor. “He knows he didn’t kill me, and I’m always thinking he’s going to come for me and finish me off.’’

And the reality was, Wallace lived just 5 miles from the Hill home.

For years, Wallace suffered.

Doctors “had no idea what PTSD was then,’’ Hill said of his longstanding medical diagnosis of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder.

For nearly 20 years, Hill suffered debilitating night terrors with cold sweats. He turned to alcohol, marijuana and pills to quell his fear, he said.

“For the longest time, I didn’t go anywhere without someone else. I looked over my shoulder for years. It was several years before I got therapy.’’

Catching Wallace

Police created a composite of Wallace’s face from Hill’s description. When detectives saw the sketch, “They knew it was George Kent Wallace,’’ Hill said.

Winston-Salem Police Officer Verlin Stockner, worked as a school resource officer and served as Hill’s mentor through the Big Brother program.

Stockner was key in connecting Wallace to the crime, Hill said.

But still, Hill had to identify Wallace. He braced himself the day the sheriff’s office called him to identify his attacker in person.

“I remember we were in the basement in an office. I sat in a chair against the wall. I was squirming and nervous,’’ Hill said. “A detective said, ‘Now Robert, we’re gonna walk him past you. He won’t hurt you. He can’t hurt you.’’’

Wallace strode past Hill and the shaken boy confirmed he was his captor.

Next, Hill and his parents would have a disappointing meeting with staff from the office of then-Forsyth County District Attorney Don Tisdale.

“The charge was assault with a deadly weapon with intent to inflict serious injury,’’ Hill said. “And I said to the DA, ‘Why in the hell not attempted murder?’’’

Prosecutors explained they did not believe they could convince a jury that Wallace had intent to commit murder.

“What else do you think he was trying to do?’’ Hill said. “Take me out on a date?’’

And once convicted of assault with a deadly weapon with intent to inflict serious injury in the Hill attack, the long-haul truck driver served only about half of his 8-year sentence, walking free again in 1981.

The assault charge is “half of what makes me furious,’’ Hill said.

Had Wallace served the full sentence, “the Foster boy and Tommy Reed and them two boys in Arkansas wouldn’t have been killed and Ferguson wouldn’t have been attacked,’’ Hill said.

Jeffrey Lee Foster and Thomas Stewart Reed

With details of the Hill attack, Wallace soon emerged as the prime suspect in the beating and stabbing deaths of Jeffrey Lee Foster and Thomas Stewart Reed, both of Forsyth County. Foster was murdered the same year as Hill’s attack and Wallace said he killed Reed in 1982, the year after his early prison release on the Hill charges.

Wallace wouldn’t admit to Gentry that he had committed the crimes until 1996, while he was sitting on death row in Oklahoma.

Wallace told Gentry during prison interviews that he picked up Foster, who was hitchhiking from Hanes Mall in Winston-Salem, and drove him to a remote dead-end road. He wrangled Foster into the back seat, lowered Foster’s trousers and paddled him before driving to a secluded area in Bethania. There, he dragged Foster from the car, placed him on his stomach and stabbed him to death, according to Gentry.

Wallace admitted the knife “blade snapped’’ in Foster’s chest, a gruesome detail that further proved Wallace’s culpability, said Gentry, who keeps the weapon tucked in his case file.

Reed, whose family home was just four blocks from the Wallace house, was leaving his job at a Winston-Salem shopping center in 1982 when Wallace told him he was ‘’under arrest.’’

He drove Reed to an abandoned lot, Gentry said.

Wallace told Gentry that when Reed refused to get in the back seat, Wallace beat him in the legs with a paddle and hammered his head with a BB pistol. He then stabbed Reed to death. Reed’s body was discovered near Piedmont Triad International Airport in 1983.

More convictions, more releases

In interviews in the 1980s, Wallace told Winston-Salem police he had moved past the aberrant behavior, according to police reports.

But he had not.

He was again arrested and convicted for impersonating a police officer in Forsyth County and returned to prison from December 1982 through February 1983, court records show.

In March 1983, just a month after his release, Wallace would be convicted yet again in Forsyth County of posing as a police officer and false imprisonment of teen boys. He remained behind bars through June 1984, a man with “a compulsion’’ to kill, Gentry said.

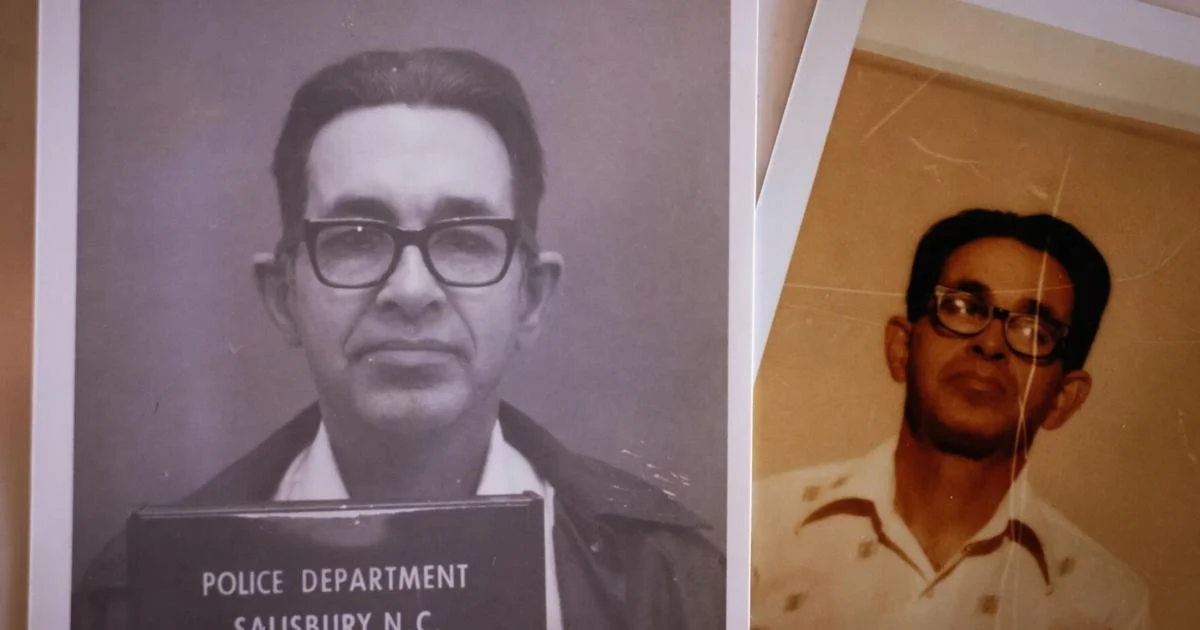

By fall of that year, Wallace moved south to a fresh hunting ground — Salisbury, detectives said.

In short order, four young men reported Wallace had approached them there — one saying Wallace decided to release him after locking him in handcuffs and leg irons, according to court records.

Convicted of those crimes in Rowan County, Wallace was sentenced to six years, but served only two, from December 1984 to October 1986.

Alerting Arkansas

After his release, Wallace moved in 1986 to Fort Smith, Arkansas, a trucking hub where he could find work, said Gentry, who still keeps the six-inch-thick Wallace case file at his Advance home.

Gentry, worried Wallace would commit more crimes there, alerted Arkansas officials that Wallace had moved there, he said.

“I called and told them that if young boys went missing, George Kent Wallace was their man.’’

Meanwhile, Gentry was curious about Wallace’s background and wondered why he turned to violence. So Gentry asked a friend who lived near Wallace’s home to speak with his mother about the criminal’s life. The elderly mom disclosed that as a teen, Wallace had been attacked by other teen boys who believed he had molested the younger brother of one in the group. After beating Wallace, they forced gravel into his rectum, Gentry said.

It wasn’t long before Arkansas police were on the phone to Gentry with questions about Wallace, he said.

At least seven young men had told Fort Smith-area police that a man matching Wallace’s description had approached them, pretending to be a law enforcement officer.

And other young men were reported missing, Gentry said.

Ross Ferguson

The big break came on Dec. 9, 1990, when another survivor like Hill, led police to their final arrest of the serial killer.

Wallace picked up Ross Alan Ferguson, 18, of Fort Smith, that day, and drove him to an isolated area near a pond where he bound Ferguson in handcuffs and leg irons. He beat Ferguson with a plunger handle and stabbed the teen at least six times before dragging him toward the pond, court records said.

Ferguson played dead as he was dragged and when Wallace removed the cuffs and leg irons, he fought back and escaped in Wallace’s rental car. Ferguson reported the crime and authorities were able to find and arrest Wallace within 30 minutes of the alert, according to police reports.

The Ferguson attack led authorities to arrest Wallace for the murders of two Arkansas teens — crimes to which Wallace pleaded guilty in March 1991.

A jury sentenced him to death that year for the beating and shooting slayings of William Von Eric Domer, 15, of Fort Smith, on Feb. 23, 1987, and Mark Anthony McLaughlin, 14, of Van Buren, Arkansas, on Nov. 11, 1990.

Posing as a police officer, Wallace had lured the young men to rural eastern Oklahoma where he killed them, court records said. The teens were discovered three years apart, submerged in the same LeFlore County, Oklahoma, pond, just across the Arkansas state line, court records show.

“I interviewed George Wallace so many times, I’ve forgotten how many it could possibly be,’’ said Gentry, who flew to Arkansas and Oklahoma to interview Wallace, sometimes at Wallace’s request.

“He would always be polite and cooperative to the extent that it almost seemed like there was a Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde within that body,’’ Gentry said.

“I couldn’t conceive how someone could be so vicious as to hit someone on the head with a ballpeen hammer or stab them and then sit there talking to me like he’s on a park bench in Mayberry.’’

Forgiveness, not fear

In August 2000, Hill was building a life in western Kentucky and enjoying his 4-year old son Mark.

He had no idea Wallace was scheduled to be put to death.

“On the day of his execution, I got a call from my brother-in-law in Winston-Salem, and he told me they were executing him that night,’’ Hill said.

“When he told me, I was overcome by something I had to do. I had no choice,’’ Hill said of his motivation to get word to Wallace that he forgave him before his 9 p.m. execution.

“I had never thought about forgiving him before. It had not ever crossed my mind. I was commanded to do it, and I did it,’’ Hill said.

“I sat up that night by myself watching (CNN) Headline News. A scroll came across the screen saying Wallace had been executed. I said, OK, it’s over, and I went to bed. After several weeks I wasn’t having night terrors any longer,’’ Hill said.

“At that point in my life, is when it all came home. My nightmares went away because I had done what God guided me to do — forgiven this guy who tried to murder me and those other people. I received evil and I gave forgiveness and turned it into good.’’

Survivors and friends

Hill forged a friendship with Ferguson just after Wallace’s execution, and in comparing life stories, the two discovered each had uncanny connections to Wallace through the trucking industry.

Hill’s father, a driver for Hennis Freight Lines in Winston-Salem, had actually been assigned as a driving partner of Wallace’s father during the early 1970s.

Hill’s dad would even recall conversations he’d had with Wallace’s father during long rides about his son being troubled.

Around the late 80s, Foster’s father, also a truck driver, broke down in his rig outside of Fort Smith. The trucker who stopped to help him with a ride?

George Kent Wallace.

Renewed interest in case (has issue)

Filmmaker Parks, who directed the 2024 miniseries about the cold case murder of Melissa Witt, “At Witt’s End: The Hunt for a Murderer’’ shown on Hulu and Disney, has not yet announced when and where the Mad Paddler series will air.

The docuseries traces 30 years of case history.

Hill says he is excited that the the four-part series has the potential to tell victims’ stories to a major audience, he said.

And the filming gave Hill the chance to reunite with Gentry, nearly half a century since their first meeting.

They met up recently at a Clemmons Applebee’s to catch up and review the case.

“It was a friendship of confidence,’’ Hill said of his bond with Gentry during the investigation. “He took care of business. He was only in the early stages of his career when he helped me. And he was always gentle with me because I was just a kid.’’

Hill further takes satisfaction that the film will examine the shortcomings of a prison system that allowed Wallace to walk out of jail early and reoffend, time and time again, Hill said.

And finally, a documentary lens will capture the scope of Wallace’s known crimes — brutal attacks that didn’t attract a large amount of media attention at the time, Hill said.

“There was an evil person out there and the world needed to know it. My parents needed to know it. Nobody at that time really realized what a monster he was.’’

The Parks documentary may give closure to some victims, but it also could serve to reopen cold cases involving similar crimes committed before Wallace’s death row conviction in 1991, Gentry said.

As a truck driver, Wallace could have committed crimes virtually anywhere, Gentry cautioned.

So the Mad Paddler case may never truly be closed.

“He could have driven his truck across the country somewhere, rented cars when he needed them to grab a kid, then get back in the truck and leave town,” Gentry said.

sspear@rockinghamnow.com

(336) 349-4331, ext. 6140

@SpearSusie_RCN

Love

0

Funny

0

Wow

0

Sad

0

Angry

0

Sign up for our Crime & Courts newsletter

Get the latest in local public safety news with this weekly email.

* I understand and agree that registration on or use of this site constitutes agreement to its user agreement and privacy policy.

Susan Spear

Get email notifications on {{subject}} daily!

Your notification has been saved.

There was a problem saving your notification.

{{description}}

Email notifications are only sent once a day, and only if there are new matching items.

Followed notifications

Please log in to use this feature

Log In

Don’t have an account? Sign Up Today