Copyright Resilience

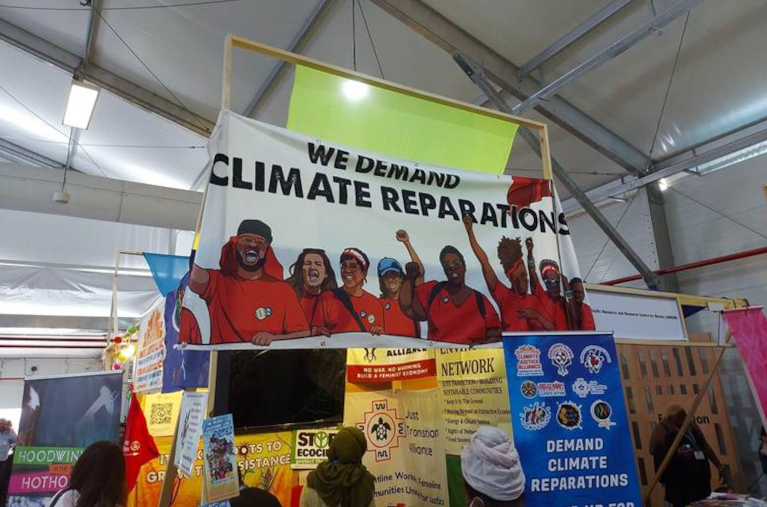

For 30 years, heads of state and diplomats have met at the Conference of the Parties (COP), to negotiate solutions to urgent climate challenges. Usually, coverage of the conferences celebrate successfully signed policies and hand shakes in the aftermath of the mega events. But how are these agreements actually reached? I meet professor of Political Science at the University College London Lisa Vanhala to talk about her fieldwork in the UN space where she witnessed the emergence of “loss and damage” – a tool to govern climate change. Vanhala is visiting Copenhagen to participate in the conference The Future of Climate Justice in Denmark and Beyond: Diplomacy, Democracy, Activism hosted by the Center for Applied Ecological Thinking at the University of Copenhagen, and Vanhala and I are joined by Anna Kirstine Schirrer, postdoc at the Center to discuss Vanhala’s work on climate change loss and damage as a new international policy. In recent years, the term “loss and damage” has emerged as a framework through which ideas of climate justice are articulated within the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. Since COP28 in 2023, loss and damage has entered governance by the establishment of the Fund for Responding to Loss and Damage. The mapping out of the coming into being of a new area of international governance is the core of Vanahala’s book Governing the End: The Making of Climate Change Loss and Damage (2025). The Fund has been celebrated as a tool to address urgent climate crises but, as Vanhala’s work uncovers, the backstage negotiations at the conferences expose the many ways that treatises are born out of a pre-existing unequal power dynamic between states. Up close, it is possible to dissect the minute details of the negotiation table that ultimately appears to be a form of diplomatic performance that reinforce the status quo rather than attempts at calling for action. Informal Relationships Expose the Continuous Global North/South Divide Vanhala’s ethnographic work centered around the preliminary negotiations that led up to the establishing of the Fund. She was struck by how careful diplomats were with showing alliances when gathered in the official conference spaces. Yet, once outside the formal premises, intimate relationships that reinforced the power divide between negotiating parties were thriving. Vanhala shares an anecdote that crystalizes the deep rooted systemic power inequality – a vignette that also forms part of the opening of her book: “On one of my fieldwork trips to Bonn for a pre-COP meeting, I decided to grab a quick dinner with my research assistant in a pizza shop. Upon walking into the restaurant, we were surprised to see mid-level diplomats and executive committee members from the Global North enjoying an informal dinner together outside work hours.” To Vanhala, the pizza dinner exposes that informal relationships flourish despite the pretense that all diplomats negotiate on an equal playing field. And that these meetings underpin the asymmetrical foundation of international governance. There is little wiggle room to address this reality: despite the injustices and frustration rooted in the prolonged discussions around accountability, diplomats from the Global South – especially where there is aid established in the relationship – are cautious to jeopardize budgets in a meeting room full of European officials. The climate change regime is stuck in division between developed and developing parties: “What we know for sure is that the cards are stacked against the countries that suffered the most from climate change even if we pretend to be negotiating on an equal basis,” says Vanhala. If It Does Not Bind Legally, Is the Fund Just Symbolic? Ideally, the Fund would encourage positive effects of incremental change but perhaps it is looking more like a victory only on paper. Vanhala points to a long list of challenges to implementing the work that the Fund sets out to do. First, there is no agreement on the definition of loss and damage. The language used is deliberately ambiguous to make the question around responsibility impossible and ultimately postpone leadership obligation and liability. Beyond the unclear language, the Fund is of a meagre size. About 700 million USD was pledged and only a dwindling half has been paid. Moreover, in order to receive funding, communities face a cumbersome application process. Resources risk going to bureaucracy instead of local organisations on the ground. Aid is often reimbursed reactively not proactively. Anna Kirstine Schirrer unpacks yet another layer that complicates the making of loss and damage as policy: “A central question of justice is the fact that the Fund is not legally binding but exists on a voluntary basis as a political mechanism.” Schirrer continues: “The Fund does not carry legal commitment and might have been unlikely to come into existence had it been legally binding. It can only really exist as a charitable act.” Photo by Lisa Vanhala from her field work at COP26 in Glasgow, 2021 Does Compensation Avoid Addressing that Some Loss and Damage is Irreparable? Climate change loss and damage was first proposed in the late 1980s and early 1990s from small island developing states vulnerable to rising sea levels like the Maldives. The initial character of the Fund was presented in diplomatic terms. But Schirrer wonders if there is a way to understand loss and damage as part of a longer history of struggle for justice: indirectly, perhaps, the Fund echoes calls for the Global North to address histories of colonialism and environmental harm, reflecting a deep sentiment of a debt that is owed for 500 years. While the original language used was centered on justice and compensation, slowly, the discourse shifted away from the idea that the Global South could demand compensation for the effects of climate change. This served developing countries’ interest in keeping the scope of the Fund as narrow as possible. Even the question around money is tricky. “Ultimately, compensation allows for the fact that there is something irreparable about climate injustice to slip,” says Schirrier. COP has been running for 30 years but institutional governance seems to focus on symbolic acts that redeem and repent empires instead of spearheading structural and fundamental changes. After all, the Fund is born out of a Global North/South divide where justice remains a voluntary and charitable gesture. This article is based on an interview with professor Lisa Vanhala conducted by postdoc Anna Kirstine Schirrer in August 2025 and written by Semine Long-Callesen. It is part of an article series published by the Center for Applied Ecological Thinking at the University of Copenhagen with Resilience.org. Photo by Lisa Vanhala from her field work at COP27 in Sharm El-Sheikh, 2022