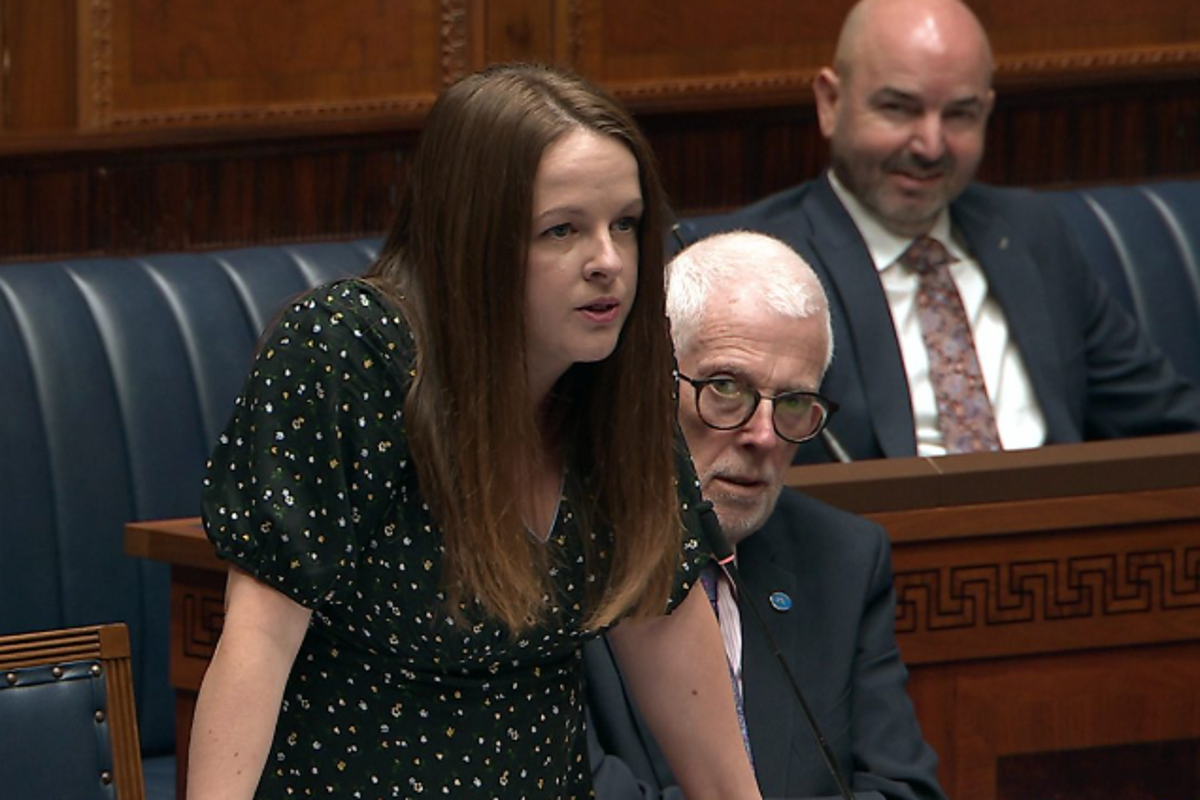

During her 20 months as attorney general, Liz Murrill has driven Louisiana into the center of some of the country’s fiercest political debates.

After the murder of conservative activist Charlie Kirk, she joined 16 other Republican attorneys general in warning universities not to impose a “tax on free speech” by charging student organizations higher security fees. She is trying to extradite a New York doctor criminally charged with violating Louisiana laws by mailing abortion pills to the state. She sued the Biden administration to block a rule that allows transgender girls to use girls’ bathrooms and participate in sports as girls.

And now Murrill, 61, is stepping into perhaps the biggest legal fight in years involving race by asking the U.S. Supreme Court to overturn a key part of the decades-old Voting Rights Act. If successful, the move could force either U.S. Rep. Cleo Fields or U.S. Rep. Troy Carter — both Black Democrats — out of Congress, to be replaced by a Republican.

By aggressively pursuing high-profile conservative causes as attorney general, Murrill has been following a playbook established over the previous eight years by her Republican predecessor, Jeff Landry. During that time, Murrill was one of Landry’s top lawyers.

Landry’s activist style as attorney general was so popular that he parlayed it into election as governor in 2023, in the same campaign cycle when Murrill won her race to succeed him.

Landry admires her work as attorney general.

“She understands the playbook better than me,” he said in an interview.

Because of her approach, Murrill is stirring speculation that she will attempt to succeed Landry once again and run for governor when he leaves office.

She downplays such talk but won’t rule it out.

“I’ve had people ask me if I’m going to run,” Murrill said during an interview. “I have never uttered the words ‘I want to run for governor.’ Ever. But I never uttered the words that I wanted to run for attorney general either until I decided to run.”

Even as they align on policy and politics, Murrill and Landry present a stark difference in personality and style.

While she and Landry favor cowboy boots, hers were gold on a recent day.

“I also have boots in hot pink and silver,” she said with a laugh. “They are really comfortable.”

When Landry was attorney general, observers described him as a politician first and a lawyer second. Those same people now describe Murrill as a lawyer first and a politician second.

While Landry is well-known for his blend of belligerence and back-slapping, Murrill exhibits a more straightforward, no-nonsense approach.

Murrill said that she and the governor sometimes have legal and political disagreements that they settle privately but said they walk in lockstep on public issues.

“There’s never been a time when I did not believe she was on the same page in representing the state of Louisiana,” Landry said.

While Murrill has drawn attention for embracing national conservative causes, she has shown a more pragmatic side, like Landry, in fighting crime on the local level. That has prompted praise from an unlikely source, Jason Williams, the Democratic district attorney in Orleans Parish.

The two were wary of each other when they first met but quickly built a partnership where Williams allows the attorney general’s office to prosecute people arrested by Troop NOLA, the Louisiana State Police troop that Landry brought to New Orleans.

As Williams notes, crime has continued to drop in New Orleans during their arrangement.

“She has been leaning in when there is a need,” Williams said. “There are a lot of things we don’t agree on. We don’t let those things get in the way of the things we do agree on.”

Like Landry, Murrill has supported the coastal lawsuit filed by the Carmouche law firm that produced a $745 million judgement against Chevron in Plaquemines Parish. Murrill has stood her ground even after the Trump administration recently filed a brief to overturn the judgement.

“I have gone to some lengths to try and explain what those cases are really about and how they are different from climate change and nuisance suits, which I do oppose,” Murrill said.

John Carmouche, the well-known Baton Rouge attorney who spearheaded the case, appreciates that Murrill remains supportive despite heat from conservatives.

“She has not backed down in applying the law to the facts,” Carmouche said. “Rather than being a politician, she is actually performing her duties for the state of Louisiana.”

Lafayette roots

Murrill grew up in Lafayette as the daughter of royalty — Mardi Gras royalty that is.

Her mother and one aunt were queens of one Mardi Gras krewe, and another aunt reigned as Evangeline, Queen of Mardi Gras in Lafayette, and her father and grandfather reigned as Gabriel, King of Mardi Gras.

Murrill served as Evangeline in 1982.

A few years earlier, however, her path to success appeared cloudy.

In 9th grade at Cathedral Carmel High School, she received all Ds and was suspended for three days after getting caught smoking in the girls’ bathroom.

Her father, Larry Baker, an ear, nose and throat doctor who was chief of staff at Lafayette General Hospital, offered this view when his daughter said she wanted to transfer to Lafayette High School for 10th grade.

“You can flunk out of public school just as well as Catholic School,” he told her. “So if you want to switch, that’s fine.”

Murrill now says she was acting out because her parents had separated recently.

“I was apathetic. I was decidedly apathetic,” Murrill said during an hour-long interview. “They knew that.”

Her mother, Vaughn Burdin Baker, a European history professor at what is now the University of Louisiana at Lafayette, took her to France and England during the summer before 10th grade. Murrill said that helped give her focus.

An 11th grade English teacher, Charlene Banna, encouraged her writing.

Murrill majored in journalism at LSU and then spent two years writing obituaries and chasing local news stories for Florida Today, a daily newspaper in Melbourne, Florida.

Murrill said she enjoyed the work but left because “I realized there was a cap on income.”

Murrill enrolled at LSU’s law school and did so well there that she held the high honor in her final year as editor of the law review.

She and her husband, John Murrill, settled down in Baton Rouge and would eventually raise four boys.

Murrill clerked for prominent U.S. Judge Frank Polozola, worked as a private attorney and taught at LSU’s law school.

The immediate aftermath of Hurricane Katrina in 2005 got her thinking about making a career change.

Volunteering at University Baptist Church, she helped distribute donated supplies to people seeking shelter in Baton Rouge from metro New Orleans. That got her interested in looking at larger societal issues, she said.

A year later, Murrill won a prized fellowship awarded by the Supreme Court that led her to spend a year at the Federal Judicial Center in Washington, D.C., a think tank that supports education and training for all the federal judges.

In 2008, Murrill applied to be deputy executive counsel to then-Gov. Bobby Jindal, a Republican.

Jimmy Faircloth, the executive counsel, hired her.

“She’s super smart, very energetic,” Faircloth said. “Confrontational in a good way. She’s really a lawyer’s lawyer.”

Murrill was a Democrat. Faircloth said he didn’t even think to ask for her party affiliation since he liked her so much.

Murrill became a political independent in 2010 and a Republican a year later, just before being promoted to replace Faircloth.

Murrill said she had registered as a Democrat at age 18 because everyone she knew then was a Democrat.

Until she worked for Jindal, “I had no real need to re-examine that choice because we had open primaries and that permitted me to vote for whoever I wanted,” Murrill said in an email. “I believed in principle in separation of powers and minimizing government intrusion in our lives, but working in government really brings home how important both of those principles are in practice not just in principle.”

Murrill spent two more years working for Jindal as executive counsel of the Division of Administration, which manages the day-to-day operations of state government.

After Landry was elected attorney general in 2015, Murrill asked him for a job.

“I thought I could never afford her,” Landry said. “She said, ‘Just make me an offer.’”

Over the next eight years, Murrill served as his solicitor general, supervising major cases that involve federal and constitutional questions. She argued five cases before the Supreme Court, winning once.

Murrill had the backing of Landry and the Republican political establishment when she was elected attorney general in 2023.

Legislators followed Landry’s lead and sacrificed then-U.S. Rep. Garret Graves, a Republican from Baton Rouge, to carve out a district that would elect Fields, a Democrat but frequent Landry ally, and ensure that the other four Republicans had safe districts.

Now Murrill and Landry are calling on the Supreme Court to invalidate Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act – which determines to what extent lawmakers and courts can include race in their calculations. If successful, that would overturn the current congressional map.

State Rep. Edmond Jordan, D-Baton Rouge, who chairs the Louisiana Legislative Black Caucus, said Murrill had consistently said the latest map passed legal muster until an August brief to the Supreme Court in which she said it was “unconstitutional.”

“It’s the polar opposite,” Jordan said. “I’ve never seen anything like it.”

Murrill said she’s not being inconsistent. She said the Supreme Court asked for new legal arguments that opened the door to argue what she and other Louisiana officials have long believed, that judges should not draw maps.

Terry Ryder, who worked as a senior lawyer for four governors, Democrats and Republicans alike, echoed the view of others who have known her a long time by saying she has taken a hard turn to the right in recent years.

“Candidates eventually become more consistent with the views of the people in the state, which is to be more conservative. That’s how you get elected,” Ryder said. “I expect her to be the next governor. She’s working in that direction. There’s only one higher position (than attorney general).”

She won’t acknowledge having that ambition.

“I think everybody is always trying to guess who’s going to run for governor next,” she said. “It’s part of the game of politics in Louisiana. That’s a long way away.”

In the meantime, she plans to run for reelection in 2027, having discarded dreams of becoming a federal judge.

“I absolutely love the job I have,” she said. “It’s a more impactful one.”