By Yuanyue Dang

Copyright scmp

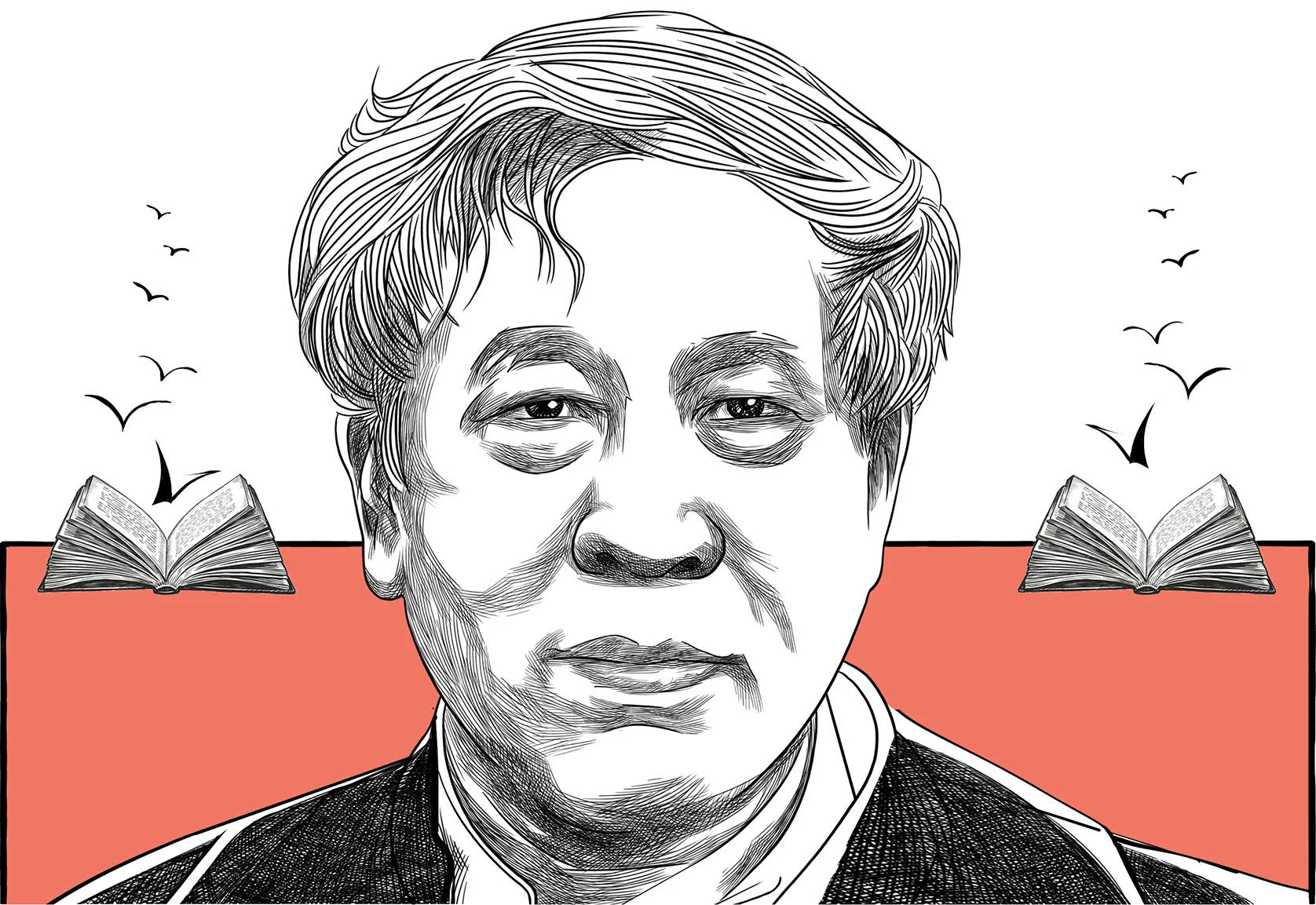

Chinese novelist Yan Lianke is considered a strong contender to win the Nobel Prize in Literature. Yan uses magical and absurd imagery to depict the realities of rural China, particularly the lives of ordinary people in the Mao Zedong era. His awards include the Franz Kafka Prize, the Lao She Literary Award and the Lu Xun Literary Prize. Yan is a professor at Renmin University of China in Beijing and a chair professor at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology. In this interview, the former soldier considers the global status of Chinese literature and discusses the censorship of his books. This interview first appeared in SCMP Plus. For other interviews in the Open Questions series, click here.

In recent years, there has been a lot of discussion about you being in contention for the Nobel Prize in Literature. Does this put you under pressure?

I was born in 1958 and am now 67 years old. At this stage in my life, the prospect of winning any literary prize no longer exerts any pressure on me or my writing. Any pressures I face now stem from within my own existence and from literature itself rather than from outside the literature and my life.

Indeed, certain past laureates have sparked controversy among readers, and such debate is perfectly natural. Although there is broad common ground in the standards of good literature, literature is ultimately not a science – it is not mathematics, physics or chemistry. Its magic and greatness lie in its capacity for diverse interpretations: benevolent people see benevolence and wise people perceive wisdom.

Fine literary works excel precisely because they offer multiple angles for interpretation, inviting varied understandings and lively discussion.

In your writing, how do you handle sensitive events in contemporary Chinese history? For example, the Great Chinese Famine, the Cultural Revolution, the Tiananmen crackdown and the Covid-19 pandemic. Do you engage in self-censorship?

I believe in the simplest principle of literary common sense: any human experience is fair game for literature. No experience is inherently nobler or more deserving of a place in literature than another.

The distinction lies in which experiences the writer knows more intimately and can probe more deeply, and their attitude towards them. The criteria I use to decide what to write about and what to avoid are simply the life experiences that evoke a more visceral, painful resonance within me.

These are likely to be the experiences that I most need to confront in my writing. In other words, I do not choose to write about – or abandon – a particular event, person or historical period simply because it is sensitive. However sensitive the subject, if I write about it, it must pierce me, revealing the human predicament and struggle within.

The social predicament of humanity remains my central and enduring focus. Although these histories and events belong to society as a whole, when I perceive the deepest human predicaments and struggles within them, they become my own unique possession.

Take the Cultural Revolution, the Great Famine, the Anti-Rightist Campaign and the Down to the Countryside Movement, for instance. I write about these major public historical events because they have become my personal experiences.

Works such as Dream of Ding Village, Lenin’s Kisses, The Explosion Chronicles and The Four Books may appear to others as reflections of societal realities and collective history. Yet for me, they embody my most singular personal experiences because within them, I perceive the profound meaning and utter meaninglessness inherent in human existence at its most troubled.

It is worth adding here that, when writing these works, the most crucial element is not merely the people, stories and predicaments within them. Equally vital is my distinctive method of crafting them. For me, the methodology of fiction often outweighs what I wish or feel compelled to write.

You once said that censorship was not the biggest obstacle to creating great literature. Do you still hold this view? Do you think that censorship prevents Chinese literature from reaching a global audience?

Indeed, I have said that the most formidable challenge for a writer is not state censorship, but the innate habit of self-censorship cultivated from childhood. When it comes to Chinese writers and literature, the world questions the system of censorship that you mention, which we term “publishing discipline”. I see no reason to evade this issue, and will share some of my reflections.

Whether it is termed “censorship” or “publishing discipline”, it does not exist in isolation. It forms part of the social system. Drawing on humanity’s social experience throughout the 20th century, when a social system encounters literature, it inevitably takes a stance and makes choices. This stems from the structure and nature of the social system itself, rather than from isolated issues such as censorship or publishing discipline.

Literature emerging under one social system will invariably differ in direction and content from literature emerging under another. The question is not whether Chinese literature should engage with the world. Rather, China’s system dictates that its literature inherently aspires to establish a distinct voice within the global literary landscape.

In other words, different social systems seek to produce literature that will stand among the world’s literary traditions rather than simply allowing their literature to merge with the global sphere.

Contemporary Chinese writers face an inner dilemma: should they become independent individuals or join a collective writing group?

On the one hand, almost every Chinese writer – including myself – lives within the state and collective. However, literature’s very nature demands that a writer be an individual, not a collective member. Today, the vast majority of Chinese writers face this choice with vacillation and indecision. Even the more astute among them attempt to straddle both worlds.

I believe that we should understand and accommodate the conscious choices that Chinese writers make regarding individuality and collectivity. However, those who try to do both will, in truth, find their inner conflicts intensified and their lives made more complex and arduous.

One point must be clarified: literature is not black and white. Adopting Lu Xun’s approach does not mean rejecting Eileen Chang’s. Nor does it mean that if one does not write like Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn or Boris Pasternak, one must inevitably write like Maxim Gorky. After all, China has now undergone over 40 years of reform and opening up, and society as a whole is considerably more tolerant of literature and writers.

“Freedom in writing, discipline in publishing” – these two phrases have long been central tenets of China’s cultural policy. In truth, they imply that what a writer chooses to write or not to write is, to a greater or lesser extent, decided by the writer themselves. Yet, within this freedom of choice, the challenge lies in setting aside worldly concerns of fame and fortune.

Many exceptionally talented Chinese writers straddle both sides of the divide. They move freely, reaping what they sow. Yet, regarding these writers, no one can deny that their endeavours are literary. Within this diligence and vast output, works of art embodying “truth, goodness and beauty” inevitably emerge.

I believe that navigating the narrow path between censorship and artistic choice and writing with such adaptability may one day yield a timeless masterpiece of aesthetic perfection. This is the wondrous possibility inherent in literary censorship and tolerance, choice and self-awareness.

You were once a PLA soldier. In what ways has your military service influenced your writing? You are known as an author of “banned books”. Does this conflict with your identity as a veteran?

I am grateful for every stage of my life’s journey. My 26 years in the military represent the most significant and prolonged chapter of my life. It was during my service that I started writing, and it was within the army that I became a writer. The seeds of becoming this particular writer were sown during my military service. Thus, my gratitude for those 26 years mirrors how every writer dedicates their entire literary life to honouring their childhood.

Many of my most notable works – such as The Years, Months, Days, Hard Like Water and Lenin’s Kisses – were completed during my time in the military. These 26 years coincided precisely with two decades of profound transformation in Chinese society.

China’s shift from isolation to openness, conservatism to modernity and poverty to prosperity all unfolded during this period. Without those years of military service, I would not be here today.

Few people know that throughout my writing career, both within the military and for most of my life after leaving, I received considerable tolerance, understanding and protection. Without that tolerance and protection, my writing would not have reached its current level.

I must confess that, before the age of 20, I had never read a single foreign novel. This is unusual among writers in China and worldwide. Back then, I firmly believed that all literature in the world was the “revolutionary literature” that we were reading at the time. It was only after enlisting at 20 that I encountered the great classics of the 19th and 20th centuries, which gradually reshaped my literary perspective.

For example, when I was 21 and had just arrived at the barracks, the first foreign novel I read was Margaret Mitchell’s Gone with the Wind, which opened my eyes to 19th-century classics. It transformed my understanding of the relationship between heroism and humanity in revolutionary literature.

After this, I wrote my earliest banned work, Summer Sunset (written in 1991 and banned in 1994). For this, I wrote self-criticisms for six consecutive months yet still received tolerance, protection and understanding from the army. I remained in my position as a “professional army writer” and later wrote works such as The Years, Months, Days, Hard Like Water and Lenin’s Kisses.

It should be noted that I did not leave the military because of the banned novel Serve the People. In fact, it was after writing Lenin’s Kisses and accepting an interview with Phoenix Television that I was compelled to leave.

After leaving the military, I experienced a sudden sense of “freedom”, which led me to write Serve the People and Dream of Ding Village in an “anarchic” manner. This subsequently earned me the label of “banned author” both domestically and internationally.

Consequently, nearly every subsequent work was accompanied by unceasing controversy, cementing my status as the “banned author” and “China’s most controversial writer”.

I wish to elaborate further on banned books here.

Firstly, a banned book is not necessarily a good book. Everything must return to the fundamentals of art and creation. As I have repeatedly emphasised, while literary history records many banned books that went on to become classics and literary treasures, there are also numerous banned works of negligible artistic merit. This phenomenon was particularly pronounced during China’s Ming and Qing dynasties.

Secondly, despite having more works banned or unpublished in simplified Chinese editions on the mainland, I have always considered myself the most fortunate and tolerated of all Chinese writers.

As my writing provoked increasing controversy, I faced relentless societal criticism, while in unseen corners, I consistently received tolerance and protection. When Dream of Ding Village was banned, for example, my workplace passed on a message from China’s publishing authorities: “You must take good care of Yan Lianke; he is a talented writer. We are only banning him because it is our job, but his work is truly excellent.”

Hearing such words brought tears to my eyes at the time. There are many such instances; without them, my writing would never have endured to this day. I possess no such formidable willpower. In truth, I am a rather fragile individual. That is why I have repeatedly stated the following across the globe: China is not what you imagine it to be, or at least not entirely as you describe it.

To a greater or lesser extent, its literary tolerance permits a writer to “write freely”, though when it comes to publication, much of the fame and fortune must be relinquished.

Finally, I have repeatedly appealed to people around the world: please do not label me a banned author or China’s most controversial writer. I am simply an ordinary novelist. An ordinary writer who is stubborn, steadfast and somewhat independent in my artistic pursuits.

Though my computer files store 17 or 18 unpublished works alongside numerous published titles that cannot be reprinted, it is this very suppression that has granted my writing greater freedom. In artistic creation, I have become a “literary anarchist”. Therefore, from the bottom of my heart, I thank not the publishing discipline or the censorship system itself, but the “tolerance” within it.

How do you view the shifting literary landscape? In an era where science and engineering are held in higher esteem, what position does literature occupy?

I must confess that matters such as the dominance of science and engineering, the digital realm, and AI-generated writing – topics of global concern and debate – have scarcely engaged my serious attention, let alone sustained reflection. I remain a quintessential literary pragmatist, focused solely on my personal creative journey.

I have never used a computer to write and continue to write my manuscripts by hand before commissioning them to be typed. Compounded by the startling speed with which I have entered “old age”, this state of affairs fills me with both sorrow and resignation.

The inescapable spectre of death has long loomed large, and that abyss now stretches before me. Thus, in recent years, my sole preoccupation has been deciding what works I want to write before I die. What form these works shall take. Whether they possess any intrinsic value or meaning. If they are devoid of purpose, I ought to cease writing immediately.

A new generation of writers, both Chinese and foreign, is focusing more and more on contemporary and personal themes, such as modern interpersonal relationships, generational conflicts, and the search for self-discovery. What are your thoughts on these changes? Beyond China’s historical events, what other current issues capture your attention?

There has indeed been a significant transformation in the way young writers engage with humanity, society, reality and history compared to their predecessors.

Ultimately, each generation should produce literature that reflects its own era. A particular epoch should produce literature that is uniquely its own. Only thus can literature evolve and progress.

However, I personally believe that the most fundamental questions of literature should concern more than just what you or I choose to focus on. Rather, they should lie in shifts within literary thought and creative innovation. Developing new modes of thinking and literary approaches is literature’s most essential creative endeavour.

One person may focus on the history of individuals and society, for example. Another may concentrate on interpersonal dynamics. I might prioritise generational conflicts and the quest for self-discovery. Others might delve into gender politics or environmental shifts.

While these are important subjects, I do not consider them to be literature’s fundamental issues. A more essential question is: what mode of thinking do you use to engage with these diverse literary resources and subjects?

Was Lu Xun great? He is the deity of Chinese literature – China’s [Leo] Tolstoy. However, the greatness of authors such as Lu Xun, Shen Congwen and Eileen Chang lies in their ability to use realist literary thinking at the beginning of the 20th century to retrospectively fill the vast void in the realist tradition of 19th-century Chinese literature.

They flawlessly completed our 19th-century literary assignment in the first half of the 20th century. This constitutes their greatness and our own shortcomings. After all, they were contemporaries of [Franz] Kafka, [James] Joyce, [Marcel] Proust and [William] Faulkner. While the latter were striving to move on from 19th-century literature, the former were compelled to use realist thinking to fill the void in our literature from that era.

The greatness of these 20th-century writers lay in their wholly distinct literary modes of thought. In other words, one 19th-century master’s greatness bore similarities to that of another. Yet each 20th-century master’s greatness lay in their differences, namely their divergent literary modes of thought.

Now that a quarter of the 21st century has passed, the tragedy of our writing lies in our collective stagnation within 19th-century realist literary thinking. Our approaches are far too similar, while fundamentally distinct modes of thought are few and far between.

Therefore, I believe that the evolution of literature hinges not merely on different subjects or focal points, but on how one employs distinct modes of thought to engage with these new subjects.

How would you describe the position of Chinese and Asian literature within the contemporary global literary landscape?

Asian literature certainly occupies an undeniable position within the global literary sphere. However, I do not believe that Chinese literature holds the significance you suggest within this so-called world literary landscape.

Over the past decade or so, the Chinese government has invested considerable manpower and financial resources in promoting Chinese literature abroad and sharing “China’s stories” with the rest of the world. Yet, in terms of actual impact, the results have not been as favourable as media reports suggest.

Specifically, when you read the biographies of Chinese writers, you’ll find that most are presented as having works translated and published in multiple languages worldwide, as if they were universally acclaimed. However, if you visit bookshops in Europe and America, you’ll find that only a handful of books by a few Chinese authors are on the shelves.

Thus, when we discuss world literature and Chinese literature today, they appear as two nearly mutually exclusive literary concepts. However, if you enter any Chinese bookshop (including online retailers), you will find that European and American literature is represented comprehensively and in dazzling abundance. A single bookshop here is almost a repository of world literature.

Must we not acknowledge this fact? Within the global literary landscape, Asian literature lacks the firm and distinct identity enjoyed by European, Latin American or North American literature. Accepting this reality means recognising that Asian literature, as a distinct category, has yet to truly coalesce or gain universal recognition.

We can clearly discern the broad contours of Japanese, Korean and Chinese literature. However, when we try to synthesise these, we find that we are unable to articulate what constitutes “East Asian literature”.

This is precisely the state of Asian literature.

Around seven or eight years ago, the Japanese author Haruki Murakami proposed the literary concept of an “East Asian literary sphere”. Reflecting on this now, it was indeed a commendable idea.

If Asian literature possessed a distinct East Asian literary tradition or cohort of East Asian writers, this could serve as a nucleus from which to develop a genuinely literary Asian literature with clear and robust direction, representative authors and successive waves of seminal works, akin to Latin American or European literature. That would be a great fortune for Asian literature and culture.

After all, figures such as Japan’s Haruki Murakami, China’s Gao Xingjian and Mo Yan, and South Korea’s Han Kang have already secured global renown for Asian writers and literature. Building upon this foundation to establish an “East Asian literary centre” is by no means an impossible endeavour. South Korean cinema and Japanese animation already lead global film and animation trends.

For Asian literature to carve out a distinctive place on the world literary map requires sustained efforts from successive generations of writers. More young authors must emerge who produce literature that is both rooted in their own cultures and truly global.

However, unless Asian literature produces a significant number of globally recognised writers and works that exert a unique artistic influence on writers across other nations and languages – works that are not merely widely available in bookshops worldwide and embraced by audiences, but also become fresh nourishment for world literature – any discussion of its significance on the global stage risks becoming meaningless rhetoric.

Do you think that contemporary Chinese literary and artistic works are spreading around the world smoothly? What is your view of China’s current cultural soft power?

It hasn’t been as smooth as anticipated. We touched upon this earlier. I once heard a leader from the China Writers’ Association quite clearly state at a literary event that there is widespread “false prosperity” in the global dissemination of contemporary Chinese literature. While this refers to literature, similar “false prosperity” can also be observed in other artistic works.

As for China’s cultural soft power, I find the term “soft power” somewhat perplexing. It implies that culture is inherently “soft” in contrast to “hard power”. What constitutes “hard power” that makes culture “soft”? For literary and artistic works to spread effectively, they must ultimately possess robust artistic merit and originality. They need to be “hard works”.

This is particularly true of literature. Rather than spending taxpayers’ money on dissemination and “going global” initiatives, the government should encourage writers to produce “hard works” themselves.

Do you currently live more in Beijing or Hong Kong? What are your thoughts on the differences between the two cities and Hong Kong’s transformations in recent years?

I divide my time equally between Beijing and Hong Kong.

The changes in Hong Kong in recent years are plain for all to see. The most striking difference is Beijing’s status as China’s political heartland. For Beijing’s residents, political life is as commonplace as daily necessities.

However, Hong Kong’s most significant shift has been the gradual emergence of a pervasive, near-routine political existence. Yet the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, where I live, remains a bastion of Hong Kong’s scientific education and research. It is my spiritual sanctuary, a garden for the soul and a dwelling place for the human spirit.

My love for Hong Kong is akin to the symbiotic bond between a farmer and the land. Like a writer and their paper – inseparable. Had I not been in Hong Kong these past years, had I not been at HKUST, I cannot imagine how wretched my life and my writing would have become.