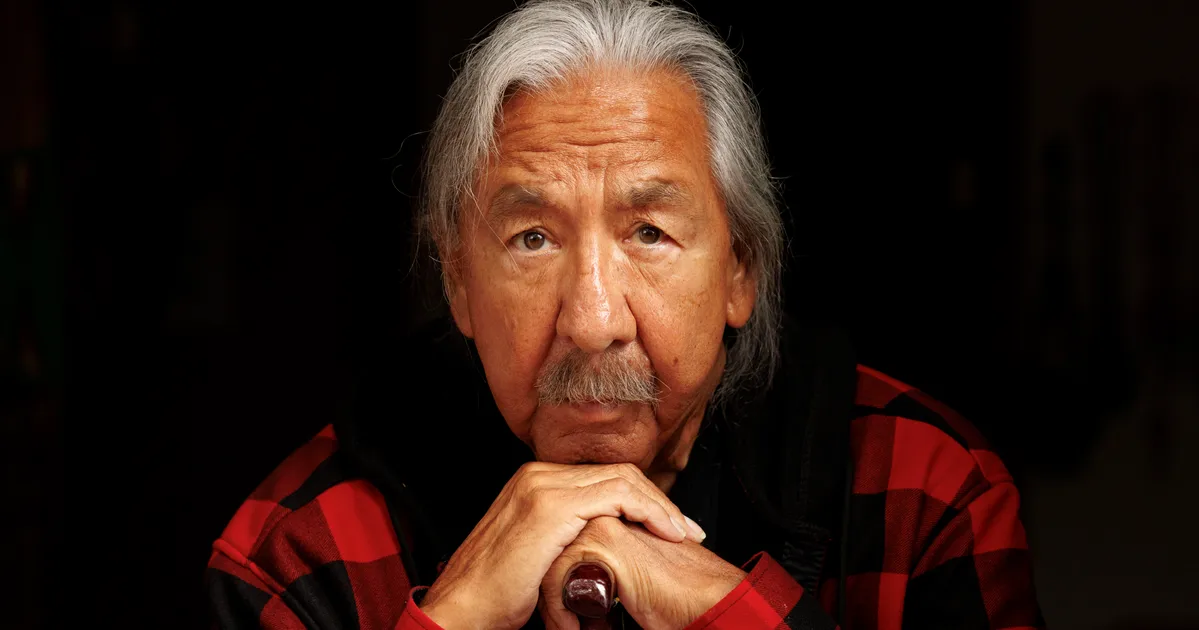

BELCOURT, N.D. — After living in a windowless, concrete box for nearly 50 years, Leonard Peltier is discovering the little joys that come with being in a two-bedroom house of his own.

He can see the sun. He has a refrigerator, and a TV with more channels than he can count. He has his now-cherished recliner, the fancy kind that lays you all the way back and, with some navigating on a remote control, pushes you up and right out of the seat. It’s where Peltier, who just turned 81, is content to spend most of his days, nestled in with a fleece blanket as a home health aide brings him rounds of coffee.

Advertisement

“Trying to look for another word, but I can’t find any, so I’ll go with the same one: awesome,” said Peltier, a term he used repeatedly to describe his life over the past seven months.

Until January, Peltier was the longest-serving political prisoner in America. An activist for Indigenous rights, he was convicted in 1977 of murdering two FBI agents, which he has always denied doing. In fact, there was never evidence Peltier killed anyone. And as he sat in prison for all those years — his story becoming the subject of countless books and films and high school assignments, the injustice of his case triggering demands for his release by international human rights leaders, legal experts, politicians, Indigenous leaders and celebrities — Peltier came to symbolize something much bigger than himself.

Between his early years of trauma in an Indian boarding school, his years of activism with the American Indian Movement and the past five decades spent behind bars, Peltier, for many, became the embodiment of so many of the injustices Native Americans and tribes have faced at the hands of the U.S. government. And the fact that he survived all of it, with a resolute attitude of resistance, has made some hail Peltier as a hero.

Advertisement

But not everyone. As much as there had been political will to release him, there had also been political calls for him to stay incarcerated for the rest of his life. Sitting in his cell early this year, after decades of U.S. presidents in both parties passing him over for clemency, Peltier didn’t think President Joe Biden would let him go home, either.

“I had already given up,” he said in an extensive interview with HuffPost at his home. “So I went and laid on my bunk, and I was thinking, ‘Well? This is where I die, I guess.’ Because I wasn’t getting the medical attention I needed. And I was really feeling sick and weak, and I figured, well? This is it. Because I’m gonna die here.”

But a nearby inmate who was listening to his radio heard the news of Biden’s clemency announcement, and shouted from down the hall, “You got it! You got it, Leonard!” A month later, he was walking out of his Florida prison and boarding a private plane home.

Advertisement

Peltier keeps Biden’s clemency order framed and prominently on display in his living room. But he doesn’t think the president freed him out of mercy or a sense of justice. He thinks Biden caved to pressure from influential Democrats and Indigenous leaders, including his own interior secretary, Deb Haaland, to let him go home.

“I don’t think he did it because he loved me or anything,” Peltier said, shrugging. “I think it was because it would have been bad politics. … I really didn’t expect anything from him.”

Advertisement

A lot has changed since Peltier went to prison in 1976. He’s essentially been in a time capsule for 50 years, and is playing catch-up to all the advances in technology he’s missed. He’s talked to Alexa. He can’t believe how savvy iPhones are, after years of using prison pay phones. Modern cars are especially wild to Peltier, considering most people he knew didn’t even have cars when he was growing up — and some were still using horses and wagons.

“I can’t believe it,” he said. “I mean, goddamn, some got everything in them.”

But some things have not changed at all. His relentless focus on fighting the U.S. government’s efforts to take civil and legal rights away from Indigenous people and tribes, and lifting up the health and well-being of Native communities, is just as firm as when he went into prison. In the 1960s, he co-owned an auto shop in Seattle that used the upper level as a halfway house for Indigenous people struggling with alcohol addiction. Today, Peltier is eager to work with Native youth to stem drug and alcohol abuse.

His activism with the American Indian Movement in the early 1970s was largely focused on stopping police brutality and defending tribal sovereignty, or the inherent rights of federally recognized tribes to govern themselves, independent of the U.S. government. Tribes entered into hundreds of treaties with the government between 1778 and 1871, and they remain the legal framework in which tribes operate today. Generally, these treaties involved exchanging tribal land for promises of government-provided health care and education.

Advertisement

But the U.S. government has a long history of breaking its promises on its treaties with tribes. And looking at the moment we’re in, Peltier is very concerned.

“We’re still in danger,” he said. “[President Donald] Trump is talking about our treaties [being] too old, and they should be abolished and everything like this. If our treaties are abolished, that means us, as a race, have been abolished completely. We don’t exist no more.”

Peltier didn’t specify what treaties he was talking about, but Trump has taken actions this year that undermine tribal sovereignty and treaty rights. In June, he withdrew the U.S. from a 2023 agreement with tribes to restore fish populations in the Columbia River. In April, his administration unsuccessfully tried to challenge birthright citizenship by citing a 19th-century legal precedent that excluded some Native Americans from birthright citizenship. His sweeping cuts to federal spending may have violated treaty rights, too.

Advertisement

“Right now, this is the only thing that we have that’s keeping us recognized as a sovereign people, as a sovereign nation,” Peltier warned. “So, we’re in danger. Nothing has changed there. We’re organizing.”

Organizing has changed too, though. Unlike his days with AIM, when Peltier and his allies were literally in the streets fighting back against police brutality and racism, today’s social justice movement includes a vast network of local, state and national groups demanding action and fighting for systemic changes for Native people and tribes. The National Congress of American Indians speaks for hundreds of tribal governments. The Native American Rights Fund provides legal aid to tribes and people. Grassroots Indigenous-led groups like NDN Collective and Native Organizers Alliance are constantly organizing on issues like voting rights and environmental protections.

Despite Trump’s current efforts to wipe out diversity initiatives in America, the country has shifted over the years, culturally and politically, in support of lifting up Native communities and people. Indigenous people aren’t isolated in their fight for social justice; they have been welcomed into broader advocacy efforts by organizations all around the country focused on strengthening civil rights for Black, brown and LGBTQ+ people.

Advertisement

Biden centered his administration on supporting Native people and tribes. He prioritized a thorough review of the U.S. government’s ugly history of Indian boarding schools. He took meaningful actions to protect sacred Indigenous sites and cultural resources, and to address the crisis of missing and murdered Indigenous women. He canceled the Keystone XL oil pipeline, a major win for tribes and environmentalists, and filled his administration with high-level Indigenous staff, not the least of whom was Haaland.

Peltier said he’s impressed with how sophisticated social justice groups have become. The energy behind them, he said, gives him hope for the next generation of activists.

“We’re more unified than we [were] when I left,” he said. “I’m reorganizing the American Indian Movement, from ‘American Indian’ to ‘American Indigenous.’ … We’re getting a lot of good responses. People want to be part of it. All over the country.”

Advertisement

It was only on his flight home in February that Peltier, a member of the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa Indians, learned his supporters had bought him a house on his reservation.

Leaders of NDN Collective, some of whom joined Peltier on his trip home, had spent months collecting money from supporters nationwide to help him get set up. Some people could only chip in $5; others gave thousands of dollars. They also bought him a car, so his friends and family — Peltier has limited vision — can drive him around the community.

Advertisement

Peltier said he wanted to cry when he learned what his supporters had done for him, but he “held it all back” because he wanted to look tough.

“I’m supposed to be a warrior, supposed to be a sun dancer, so you can’t be crying in public,” he said, referring to the Sun Dance religious ceremony practiced in Native cultures in the Great Plains region. “Trying to be a traditionalist, you know? We believe that as warriors, sundance warriors, we don’t believe in crying like a baby.”

He’s taken trips around the community, visiting his old childhood home and attending a recent powwow, where local Indigenous residents danced and celebrated his return. But Peltier seems most happy when he’s holding court from his recliner. His favorite thing to do is “just bullshitting like this,” he said, and that’s what he’s been doing for months, hosting a steady stream of visitors at his house, many of whom are strangers who traveled to this remote town 20 miles south of the Canadian border to bring him gifts and well wishes.

Advertisement

His house, which sits at the end of a nondescript dirt road, feels more like a museum than a private residence. Every inch of wall space in his living room is covered with vibrant, elaborate paintings made by Peltier over the last 50 years, before his eyes went bad. Rows of colorful beaded necklaces hang from the walls, a backdrop for one apparently very effective strip of fly tape dangling from the ceiling. Across the room from his recliner, a large bookshelf is overflowing with feathers, painted animal skulls, sage sticks, faded photographs of ancestors and friends, and unopened packets of Gambler pipe tobacco.

He has even more of his paintings on display in his bedroom — he keeps dozens of others locked up in safes — in addition to dream catchers and a poster from Haaland’s 2025 campaign for New Mexico governor. A piece of paper is taped to his bedroom door with a printed message: “DO NOT ENTER.” Just below it, in tiny letters, it reads, “UNLESS INVITED.”

Advertisement

Peltier can get around his house with a cane or a little assistance from someone, but most of what he needs is within arm’s reach from his favorite chair. His cellphone sits on a small table to his left, propped up for easy access to take all the calls coming in at a jarringly loud decibel level. To his right, a small table holds an array of items he might need at any given moment: fly swatters, the TV remote control, a bottle of hand sanitizer and three pairs of sunglasses. A pile of unopened letters and postcards also awaits his attention here.

He’s never alone. He has two home health aides who alternate between 12-hour shifts at his house. Old friends drop by. Managing all the visitors and media requests for interviews has been so overwhelming that Peltier’s own family has had a hard time getting in the door.

“My children. My grandchildren. Too many people,” he said. “But you can’t say no to them. They helped get me out of prison. They fought for me.”

Advertisement

It was a long fight.

The U.S. government put Peltier in prison after convicting him for murdering two FBI agents during a 1975 shoot-out on Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota. But it got caught threatening and coercing witnesses to lie under oath, excluding evidence crucial to Peltier’s defense and hiding exculpatory evidence in order to do it. The reality was the FBI and U.S. Attorney’s Office desperately needed to blame someone for the high-profile deaths of the two agents, and all of Peltier’s other co-defendants had been acquitted based on self-defense. There was nobody left to blame — except Peltier.

Incredibly, the U.S. government later admitted it never did figure out who shot those agents. The U.S. attorney who originally prosecuted Peltier in 1977, Lynn Crooks, told the 8th Circuit Court of Appeals in 1985, “We don’t know who killed the agents or what actual participation [Peltier] may have had.” A federal judge on that court, Gerald Heaney, later said the FBI deserved equal blame for the shoot-out that day and called for clemency for Peltier.

Advertisement

Another U.S. attorney who had previously helped put Peltier in prison, James Reynolds, later urged his release and conceded, “We were not able to prove that Mr. Peltier personally committed any offense on the Pine Ridge Reservation.”

The million-dollar question for decades was always, why is this person still in prison, after all the misconduct that was revealed in his case and despite so many pleas for his freedom, from powerful voices ranging from Nelson Mandela to Mother Teresa to Pope Francis? As Peltier’s former attorney Kevin Sharp once put it, the answer was simple: politics, because the FBI was complicit in the misconduct that led to Peltier being imprisoned in the first place.

“In order to get clemency, you have to get the FBI on board. They have an inherent conflict. You have to get the U.S. Attorney’s Office on board. They lied to get him in prison. They have an inherent conflict,” Sharp told HuffPost in 2021. “They’re not going to say, ‘Oops, sorry.’”

Advertisement

“It’s this holdover with the FBI,” he added.

Some U.S. presidents were close to releasing Peltier, particularly Bill Clinton. But he backed off his apparent plan after hundreds of FBI agents protested outside the White House in 2000 in an unprecedented show of public opposition by the bureau, and after being privately lobbied by his friend and former fellow state attorney general, Bill Janklow.

Biden knew he was defying FBI leadership by granting Peltier clemency in January. Weeks earlier, then-FBI Director Christopher Wray expressed his “vehement and steadfast opposition” to Biden’s apparent plan, and the FBI Agents Association ripped the president for his action afterward, saying the group was “outraged.”

Still, the FBI seemed to scramble to defend its position in recent years. When contacted by HuffPost for requests for comment in stories about Peltier, it often provided the same boilerplate statement that was wildly outdated and based on evidence that has since been disproven. The FBI still hasn’t publicly addressed the wider context of that 1975 shoot-out, either: the evidence that the bureau itself was intentionally fueling intra-tribal tensions on that reservation as part of a covert campaign to suppress AIM’s activities. Peltier, an active AIM leader, was a prime FBI target.

Advertisement

An FBI spokesperson did not respond to requests for comment.

Even when Biden released Peltier, he did so with a nod to the FBI. He put Peltier under home confinement instead of pardoning him, which would have meant Peltier was fully free and essentially forgiven by the government. Instead, Peltier is serving out the remainder of his two consecutive life sentences at home, with restrictions on his activities.

Peltier has been fighting to loosen those restrictions, of course.

The Federal Bureau of Prisons, which oversees his home confinement, initially told him he wasn’t allowed to have a car, but now he can. He wasn’t originally allowed to travel more than 100 miles from Belcourt, but now he can with a special pass, for medical reasons. The prison bureau also told him he wasn’t allowed to have a girlfriend, which may have infuriated Peltier more than anything, as he made it very clear he loves the company of women.

Advertisement

“I said, ‘What the hell, man?’ You know, why can’t I have a girlfriend? What’s that got to do with this shit?” Peltier said, noting he has a girlfriend in Minnesota. “So they said, ‘OK, you can have a girlfriend. But she can’t spend all night.’ Really.”

He pushed back on the bureau some more and now he’s allowed to have a girlfriend and she’s allowed to spend the night. She just can’t move in.

Advertisement

In the hours that we spoke, it was easy to forget that this wasn’t just a casual conversation with someone’s grandpa. Peltier had lots of anecdotes to share from his long life. He talked about his health, which has greatly improved over the last several months. He gushed about his elementary-school-age granddaughter becoming a strong swimmer, pointing to a photo of her pinned to the wall next to his recliner.

But his 81-year-old body is churning with rage. Peltier’s memory is remarkably intact, and he has a wealth of stories he wants to tell, involving decades of U.S. presidents and major moments in American history — all of which inevitably lead back to him losing 49 years of his life to maximum security prisons for a crime he maintains he didn’t commit.

“I’m pissed off,” he said sharply. Asked how often he wakes up furious about what happened to him, he replied without hesitation, “I think almost every day.”

Advertisement

Peltier said he could have gotten out of prison “a long time ago” if he’d been willing to lie and say he shot those FBI agents, but he wouldn’t do it. He also said he wasn’t willing to falsely accuse others of the crime to secure his own freedom.

To throw a fellow Indigenous ally under the bus like that would be “treason to my people,” Peltier said.

Asked if he’d ever considered saying he was guilty of murdering the two FBI agents just to get out of prison sooner, he abruptly rejected that option. “My dear, I took an oath to fight for my people,” he said. “I took an oath for our lives. They were trying to terminate us.”

Advertisement

Peltier brought up the U.S. government’s so-called Indian termination policy, a series of laws put in place from the 1940s to the 1960s aimed at assimilating Native Americans into mainstream culture by abolishing tribes and forcing Native Americans to relocate to urban areas. The policy was reversed in 1970, but it caused lasting damage to tribes and Native communities, namely through the loss of land and disruptions to cultural practices.

“We’d be gone as a race of people” if those policies had continued, Peltier fumed. “One of my uncles brought the newspaper home, I was probably 5 or 6 years old, they said, ‘Look at this, they’re saying we’re the vanishing Americans. They don’t know what happened to us.’ That was the cover of Look Magazine. Grandma started crying, she said, ‘What are they saying that for? We’re still here, look at us. Right? Why are they doing that?’”

Advertisement

“I don’t give a shit if they ever know,” Peltier fired back. He said the bigger question is why dozens of AIM members and allies were murdered on Pine Ridge Reservation between 1973 and 1976, during the years of high tension between tribes and the federal government.

“Nobody wants to say anything about Joe Stuntz,” he said, referring to an Indigenous AIM member who was killed in the 1975 shoot-out with the FBI agents, and whose death prompted no legal action. “What about them 62 people who were killed? Who wants to know?”

“They’re not doing a goddamn thing about them,” he continued. “But those two white people?”

Advertisement

Peltier’s puppies broke out of the basement as the interview was wrapping up.

His daughter, who had been drifting in and out with a headache, had just adopted two baby huskies and they ran wild as Peltier beamed and shared their names in Anishinaabe and Lakota, his Native languages. It was one of the many surreal moments of this visit, watching Peltier switch between being an iconic and controversial figure in the Indigenous rights movement, and an 81-year-old man hocking loogies into a can and talking about his dogs.

He has lots of big plans ahead, even in his advanced years. He wants to record an audiobook about his life, because writing books by hand, which he’s done in the past, “was a fuckin’ killer.” He wants to transform his garage into an art studio and get back to painting. He’d need to fix his eyes first, so he’s been talking to Mayo Clinic doctors about procedures that could help his vision. He’s prepared to travel to the Mayo Clinic based in Minnesota if they can help.

He’ll need a special pass from the Bureau of Prisons to go, though.

Peltier’s home health aide had been sitting quietly in the kitchen throughout the day. A woman in her early 30s, she said she’d only been on the job for a few weeks, and politely smiled when asked if it’s been annoying having so many people coming in and out of the house. She said no, and conveyed that she, too, feels how surreal it is being around Peltier.

Advertisement

“I learned about him in school,” she said. “We had to write papers on him.”