Copyright Cable News Network

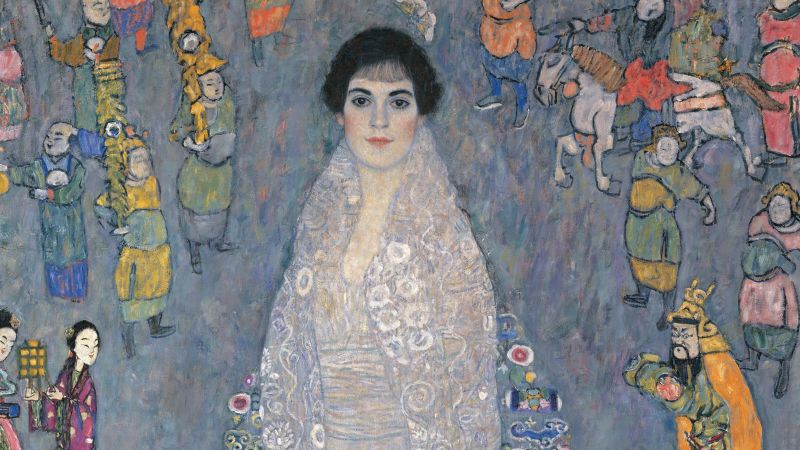

Two years ago, Gustav Klimt’s final portrait — a vibrant portrait of an unidentified woman with a fan — topped the artist’s auction record when it sold for a staggering $108 million. The Austrian painter’s record is expected to be shattered again by a monumental, six-foot-tall portrait of a young heiress that was looted by the Nazis and nearly destroyed during World War II. Rarely seen for decades, it hung in the home of the Estée Lauder heir Leonard A. Lauder until the last years of his life (he passed away in June). Next week, “Portrait of Elisabeth Lederer” is expected to sell for above $150 million as the top lot in a sale of Lauder’s collection, hosted by Sotheby’s. The collection, which includes two other works by Klimt — both landscapes of Lake Attersee, estimated above $70 and $80 million — could fetch more than $400 million combined. Among the artist’s works, the portrait of Lederer, the daughter of his wealthiest Viennese patrons, is less known. Completed two years before Klimt’s death in 1918, the portrait features her in a gauzy, ornamental robe, surrounded by motifs from Chinese art. For many years, she kept a watchful eye over Lauder’s Fifth Avenue home in New York, with only occasional outings to be shown nearby, once at the Museum of Modern Art and a handful of times at Neue Galerie New York (founded by his brother). In 2017, however, Lauder loaned it to the National Gallery of Canada for its first extended stay, where it remained until earlier this year. While in his home, the painting was a jewel of his collection, first displayed in his living room, then relocated to his dining room to make room for a large Cubist work by Fernand Léger, according to the art historian Emily Braun, who worked as Lauder’s art advisor for nearly four decades. “He ate lunch whenever he was at home, and lunch would be at a little round table right by the painting,” she said over the phone. Just a short walk away, at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, millions of visitors each year pass by Klimt’s companion portrait of Lederer’s mother, Serena. Painted around 15 years prior, the stylistic shift between the two works is apparent. Serena’s portrait is wispy and spare, contrasting the bold, lush qualities of Elisabeth’s composition. Yet both have the same dark, potent gaze, Braun notes. “You’ll see that Klimt is either mesmerized by (Serena’s eyes), or is smart enough a painter to know to draw out this incredible coal blackness,” she commented. Marked by tragedy Both paintings avoided a calamitous end during World War II, when Nazis impounded the Lederer’s vast art collection for more than a decade. Many of their works by Klimt were shown in a 1943 exhibition in Vienna, then stored in Immendorf Castle, which burned down at the end of the war. But the family portraits, excluded from the exhibition because of their Jewish heritage, were separated and ultimately spared. Elisabeth Lederer, just 20 years old at the time she sat for Klimt, was “an incredibly tragic figure,” Braun said. “Thank god this portrait survives.” Lederer lost everything before the war and died before it ended, at age 50, with the exact circumstances unclear. In the 1920s, as fascism began casting a long shadow, she became protestant and married a baron, but he divorced her just before World War II, the same year their young son died. Her family fled, but she remained in Vienna. She was vulnerable as a single Jewish woman, as Sotheby’s noted, so she claimed that Klimt, who died in 1918, was actually her father. “She was protected to a certain degree by this fabricated half-Christian, half-Klimt paternity, which was a ruse that was aided and abetted by her mother,” Braun explained. Klimt was a close family friend and her childhood drawing instructor, but he also had a reputation — allegedly fathering a number of children out of wedlock — “so this was just another example that was not far-fetched,” she added. A late-career masterwork Some works by Klimt have been the center of long sagas of recovery and restitution, but in 1948, Lederer’s portrait was returned to her brother, Erich, who appears in drawings and paintings by Klimt’s friend and peer Egon Schiele. It remained in his possession until late in his life. The art dealer Serge Sabarsky acquired Lederer’s portrait in 1983, and sold it two years later to Lauder, who had taken a prudent interest in Klimt’s work. In the US, Klimt was a relatively obscure figure until the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum staged a joint exhibition with Schiele in 1965. Lauder, who was Hungarian and Czech, began collecting his works in the 1970s in part due to his own family’s ties to the region. “I can’t emphasize enough that he was a real historian. He was fascinated by European history… and cultural history,” Braun said of Lauder. “So on the one hand, you have his direct family connection and heritage. On the other, you have the historian’s awareness of Klimt and what he represented at the apex of Viennese culture. And thirdly, you have the sheer beauty and aesthetic strength of these pictures, which he recognized immediately. He had an incredible eye.” Klimt may be best recognized by his golden period, during which he produced the gilded Art Nouveau icons “The Kiss” and “Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I.” But in the years before his death, at age 55, his geometric motifs became more fluid, his brushstrokes looser, and he was greatly influenced by East Asian art, of which he was an avid collector. The figures he painted around Lederer in her portrait were likely based on works of Chinese art that Klimt owned, according to Sotheby’s, while the Chinese dragon robe she wears in the painting was meant to be a striking symbol of power. It has been said that the artist did not want to part with the painting, which took years to complete. For a long time, the portrait of Lederer still carried the weight of her marriage — but that changed while in Lauder’s possession. Though Lederer was just 20 years old and unmarried when Klimt painted her, her portrait was called “Portrait of Baroness Elisabeth Bachofen-Echt” when he acquired it. Braun advised Lauder to change it, she recalled. “I said to Leonard, ‘It’s not right.’ This was commissioned while she was single. It was commissioned by her family, and her husband treated her so badly — why are we calling it by this title?” Braun said. “So we reverted to the original title, and that’s what it’s called now.”