There’s history (the past) and history (the official account), and then there are the huge, colorful, time-bending canvases of the American artist Kerry James Marshall, which blend Black history and art history to show us that there is never just one way of seeing the world.

There are many kinds of history in “The Histories,” the largest survey of Marhsall’s work ever presented in Europe, which opened at the Royal Academy of Arts in London last week. Seventy canvases depict the Middle Passage, the slave rebellions of the American South, and the U.S. Civil Rights and Black power movements. But there are also more daily scenes and sites: a barbershop, a club, domestic interiors and housing projects, like the one Marshall and his family lived in after moving from Birmingham, Ala. to Los Angeles in the 1960s.

Some of his historical scenes explore episodes that artists have hardly tackled before, like the works in a new series called “Africa Revisited,” depicting the powerful African leaders and merchants who took part in selling Africans to European slave traders. Marshall recently told The New York Times that he didn’t understand why anybody would find these depictions controversial: “The history is what it is,” he said.

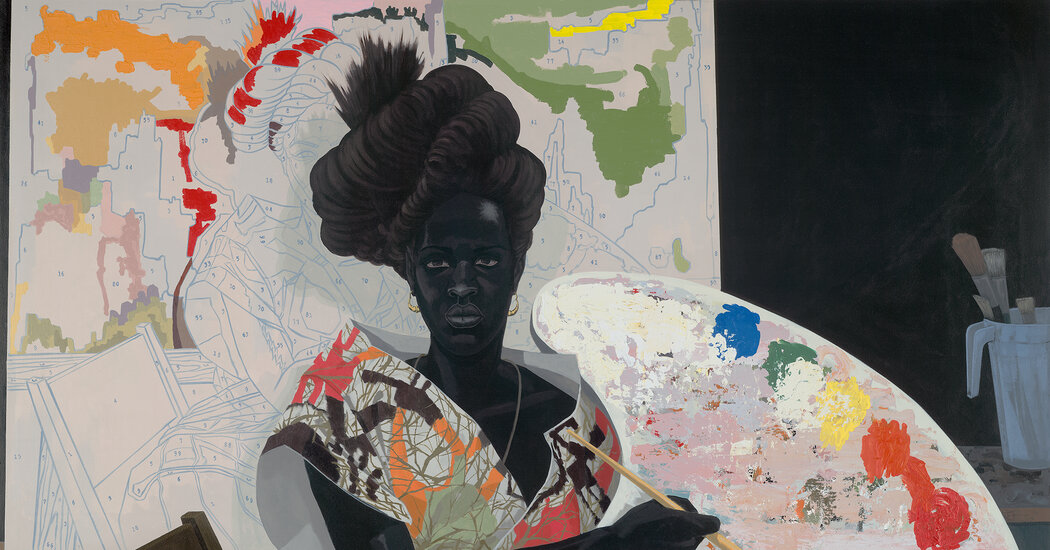

There is a radical flatness to the works, which are sometimes painted on fiberglass, PVC panels or wood. Paintings on canvas are frequently tacked directly to the wall with metal grommets. Figures are depicted in a compressed picture plane, and scenes are so packed with detail that they have an almost graphic quality.

Pattern and texture keep the eye moving, glimpsing something new in each moment. In some, song lyrics and musical staves curl through the image like atmospheric captions: “Baby I’m for re-al do do do de dah,” reads one that hovers in the air above a couple slow dancing in their living room. In others, the surfaces of the works are disrupted by collaged elements — drawn images, book covers, calendar pages, gold and silver glitter — as if different visual universes have collided.

“We go to museums and art galleries to see and think about remarkable things,” he added. “I try to make sure some of those remarkable things are inextricably oriented around the representation of Black people.”

Each work insists that the viewer is an active participant. An early room in “The Histories” shows a suite of works inspired by Ralph Ellison’s 1952 novel, “Invisible Man,” whose narrator describes the conditions of social invisibility he experiences as a Black man in America. “Two Invisible Men Naked” (1986) is a diptych, with a seemingly pure white image in a white frame on the left, and a black image in a black frame on the right, featuring a flashing pair of eyes and a cheeky full grin.

Looking again, we see that the left half also contains a figure, white on white, that seamlessly blends into its surroundings. One reading could be that it’s easier for some to fit in than others. At the same time, the work participates in the long art historical tradition of monochromes, whose surfaces can be read only by looking slowly.

Another early work also plays with literary references and ideas about color: “A Portrait of the Artist as a Shadow of His Former Self” (1980). This one also shows a Black man painted in a flattened swath of black. The eyes and grin are exaggerated, once again, but this time the figure is wearing a suit and hat. He appears as a cartoonish shadow, who seems uninterested in disappearing. Perhaps he is embarking on a career as a painter; perhaps he has been rendered one-dimensional by the art history that produced him.

If Marshall’s works are about representing Black people, they are also a nuanced tour through the canon of art that has typically excluded them. His works flicker with art historical references that, for those in the know, will delight like old friends.

“Past Times” (1997), — which recalls George Seurat’s “A Sunday on La Grande Jatte” (1886) and “Bathers at Asnières” (1884) — shows a picnic in a Chicago park, with a family of four relaxing in lush waterside greenery while a speedboat and a water skier zoom past in the background.

“School of Beauty, School of Culture” (2012) shows the interior of a lively women’s beauty salon, its walls covered with ephemera: ads for hair and skin products, a signed Lauryn Hill album cover, a poster for a retrospective by the artist Chris Ofili. In the foreground, a strange object, bright yellow and pink, floats at an angle. It is the head of Disney’s Sleeping Beauty, flattened and twisted, just like the famous skull in Hans Holbein the Younger’s “The Ambassadors” (1533): Disney as the great mortal icon of the American dream.

When we look at Marshall’s work, we are always aware that we are looking at a carefully constructed image, and it often seems the figures we behold are in on their own framing. They stare out, watching us watching them, and together we are all part of the project of art, which is a project of looking.

In two untitled paintings in an early room of the “The Histories,” the viewer, in fact, becomes the subject. In both, an artist — a woman in one, a man in the other — is at work, holding a huge palette encrusted with paint in vibrant hues. The painters look out at us with great concentration, wondering how to depict us as they work on some new vision. The great question becomes not what are you looking at, but who you, the viewer, are. And what you want to see.

The Histories

Through Jan. 18, 2026, at the Royal Academy of Arts in London; royalacademy.org.uk.