Copyright The New York Times

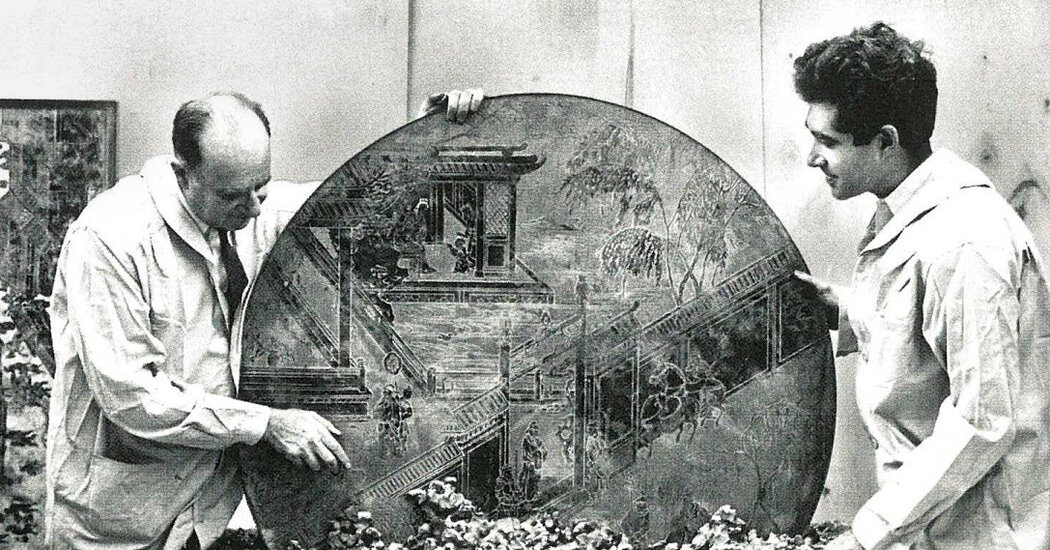

In the heyday of midcentury modernism, when many American living rooms were filled with futuristic mass-produced furniture — or restrained suites of bentwood and cane — Philip and Kelvin LaVerne, a father and son, were making idiosyncratic pieces by hand, from bronze, pewter and glass, in their Manhattan studio. It wasn’t conventional furniture, though it was functional. They drew from antiquity, using techniques and themes from Etruscan art, Greek mythology and ancient Chinese works. Sculptural forms — bronze nudes and abstract shapes — served as table bases; tabletops were often “paintings,” etched scenes rendered in enamel. The work was opulent — and pricey, selling for thousands of dollars for a single piece. And it was unlike anything else being made at the time. The Vatican, Philip LaVerne said, once commissioned a table depicting a work by Michelangelo. John V. Lindsay may have had a bronze wall piece hanging at Gracie Mansion during his two terms as mayor of New York, from 1966 through 1973. (There’s a photo of him showcasing it in the LaVernes’ files.) Dorothy Carnegie, otherwise known as the wife of Dale Carnegie, the business guru and author of “How to Win Friends and Influence People” — and the president of her husband’s company after he died in 1955 — was a collector. “It is so breathtaking that I feel inclined to just sit and dream over it,” Mrs. Carnegie wrote in a 1971 letter about a coffee table the LaVernes had made for her home in Forest Hills, Queens. It was one of many mash notes they received over the years and tacked to the walls of their showroom on East 57th Street. “It matters to me who has my work,” Philip LaVerne told The Plain Dealer of Cleveland in 1968, explaining that he turned away buyers who didn’t meet his standards. Philip LaVerne died of colon cancer in 1987. Kelvin LaVerne, who continued the business for another decade, died on Sept. 24 at his home in Manhattan. He was 88. Kelvin’s grandfather, Max LaVerne, had been an itinerant painter who made murals for churches and synagogues. “The way I heard it,” Darren LaVerne said, “Max was the kind of guy that went out for a cigar and came back three months later.” One day, when Philip — the eldest of nine children — was 16, Max didn’t come back at all. Philip had been helping his father since he was 12, and now he went to work full time to support the family. During World War II, he served as an Army photographer. When he returned to civilian life, he began to make furniture and decorative pieces: mirrors, murals and television cabinets. (His brother Erwine, with his wife, Estelle, and another brother, Louis, were also in the decorative arts business, designing hand-printed wallpaper and fabrics.) Kelvin LaVerne was born on April 17, 1937, in the Bronx, and began working for his father when he was a teenager. He attended the City College of New York and the Parsons School of Design and studied at the Art Students League of New York, where he met Agatha Rowan. They married in 1971. In addition to their son Darren, she survives him, along with another son, Sean; a daughter, Simone LaVerne; and three grandchildren. Kelvin and his father often traveled to Greece and Italy for inspiration, spending months there sketching. Their fabrication methods were laborious and often dangerous. They developed a secret recipe to age their work, a mixture of chemicals and soil in which they would immerse a piece and freeze it for weeks, until it acquired a patina to their liking. They cast bronze using the lost-wax technique, an ancient and involved process. They brazed their work, a kind of welding. They sliced fretwork by hand — a tricky endeavor, often resulting in bloodied fingers. A single piece could take months to complete. Cristina Grajales, a Manhattan gallerist, was among those who bought pieces for herself then. In 2008, she put on a solo show of the LaVernes’ work. “It’s the perfect marriage of art and design. It took my breath away,” said Ms. Grajales, who still carries their pieces. (A set of interlocking bronze tables, each with a nearly life-size sculpture perched on the edge that depicts Orpheus and Eurydice, the doomed Greek lovers from mythology, sells for $150,000.) Evan Lobel, another gallerist, was so taken with the LaVernes’ work that he collaborated on a book with Mr. LaVerne, “Alchemy: The Art of Philip and Kelvin Laverne” (2024). The interior designer Steven Gambrel, who collects the LaVernes’ work for himself and his clients, praised the robustness of the bronze, the artistry of the finishes and the narratives embedded in each piece. He added: “Is it art, is it furniture, is it architecture? I don’t know!”