Copyright Norfolk Virginian-Pilot

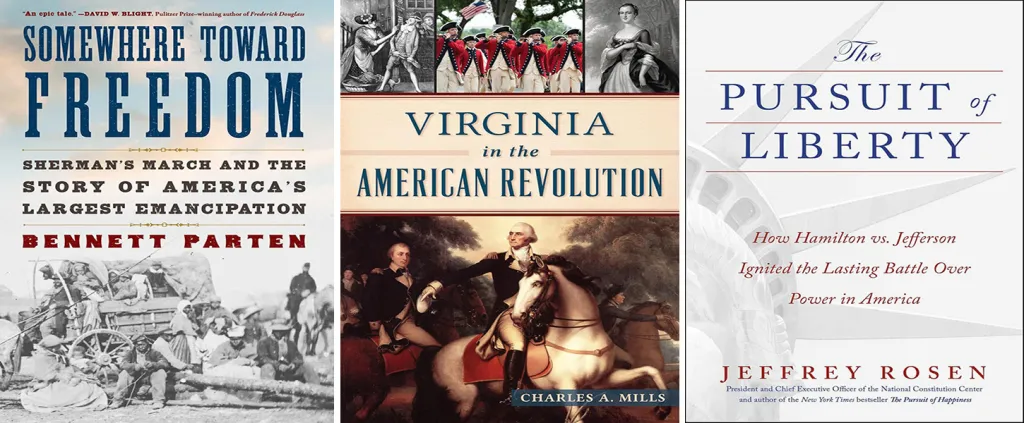

Gen. Ulysses S. Grant embraced Gen. Robert E. Lee’s surrender at Appomattox, but it was Gen. William T. Sherman and his destruction of Atlanta — and subsequent march through Georgia — that paved the way for the end of the Civil War. Forty-five years ago, North Carolina/Virginia author Burke Davis, a long-time Colonial Williamsburg writer who lived in Williamsburg, penned “Sherman’s March: The First Full-Length Narrative of General William T. Sherman’s Devastating March through Georgia and the Carolinas” (1980). The highly acclaimed volume was written in the years of the Lost Cause — the effort of Southerners to remember the Confederate cause in a positive light. Davis attempted to portray the story of the blue-and-gray soldiers and the women and men who tried to protect themselves while Sherman’s soldiers raided through the land. Blacks, who gained their freedom during the march, and slavery did not figure much in Davis’s account. Historian and author Bennett Parten made up for the omission with his recent book, “Somewhere Toward Freedom: Sherman’s March and the Story of America’s Largest Emancipation” (Simon & Schuster, 272 pgs., $29.99 hardback). Parten’s story — Sherman’s story — is “a stark reminder that emancipation is a story about how slavery died as much as about how people became free.” While using Sherman’s military march as a spine for the narrative, Parten tells the struggle of the Black Georgians who gained their freedom and then faced the challenge of coping with it. Tens of thousands of them followed Sherman’s 65,000 troops in their march from Atlanta to Savannah. Initially, Sherman’s troops “showed little compunction about taking what they wanted. Foragers rifled through slave quarters (as well as white plantations), ransacking the homes” and carrying away goods and valuables of nearly everyone, Parten writes. Sherman did not want the formerly enslaved persons to join or follow his march. Although he knew it would not happen, Sherman told the freed men and women not to follow, Parten outlines. But the once-enslaved did by the thousands. “But following the army was generally seen as a step toward security, perhaps the most fundamental freedom of all,” Parten describes. Looking at the march through the eyes of the formerly enslaved puts the march as described by Davis into a more vivid perspective. The Georgian Blacks, whether within the physical confines of the march or not, believed that just being within the proximity of the march immediately gave them freedom. That was another aspect that Sherman had to cope with amid his journey. Parten stresses that “the last thing the army wanted was to have thousands of freed people disrupting its operations” — freedom or no freedom. Thus, at the end of the march, those same thousands found themselves in Savannah and its surrounding area with nothing — no homes, little food and no jobs. The federals then faced the daunting task of what to do with all the now-freed people. The most amazing part of the saga is how Sherman and his superiors decided the way to handle the Black marchers was to scatter them among the coastal islands of Georgia and South Carolina and provide opportunities for land ownership. That story, however, may lead to another book beyond the war’s end. A Revolutionary War in Virginia companion book Back in the day when I was a student at William & Mary, John E. Selby was a history professor and I was one of his students. Twenty years later, he wrote an iconic book, “The Revolution in Virginia, 1775-1783.” Through the decades, it has become the standard by which the Revolutionary War in Virginia is portrayed. In fact, one reviewer in 1988 said Selby’s book “is a triumphant combination of solid research expressed in felicitous prose.” Today’s readers might not want to use that combination of words to describe Charles A. Mills’ new work, “Virginia in the American Revolution” (The History Press, 144 pgs., $24.95), but they definitely will see it as an important and valuable companion to Selby’s. Mills provides a brief overview of the military aspects of the war (Part 1), and then adds four additional parts with more features. He examines civilian life — writing about slavery, religion, modes of travel, family life, clothing of the period and amusements such as Revolutionary War sites you can visit. In describing the military life of the age, Mills makes the distinction between militia and minutemen and the Virginia Line and Continental Line as well as how music is played on the battlefield. He also writes about various significant Virginians and unusual events during the war. For example, many people do not know of Virginia’s own Paul Revere: John “Jack” Jouett. The saga of Jouett’s ride from Louisa County through the backwoods to Charlottesville to warn Thomas Jefferson and the General Assembly, which had vacated Richmond in an effort to stay away from the British, is a story in itself. Jouett’s plea, “The British are coming,” kept Jefferson and most of the assembly safe. Thanks, Mills, for your creative volume. Life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness Jeffrey Rosen, lawyer and U.S. Constitution scholar, has written the second book in a series of constitutional contemplations, “The Pursuit of Liberty: How Hamilton vs. Jefferson Ignited the Lasting Battle Over Power in America” (Simon & Schuster, 448 pgs., $31 hardback). Bestselling author of “Pursuit of Happiness,” Rosen offers a lively and vivid discussion of Thomas Jefferson’s and Alexander Hamilton’s tug-of-war — the balance between liberty and power, which is a story that continues today. It wasn’t settled 230 years ago and won’t be settled in today’s democracy, he contends. Pulitzer Prize-winning author Jon Meacham writes that Rosen “has given us another great gift: a wise, searching, and illuminating study of the tumultuous dawn of American politics.” He adds it is a clarifying lens on our own time. In that vein, the most remarkable part of the Jefferson-Hamilton disagreement — the power of the chief executive— can be examined today when looking at whether recent presidents have consolidated power or subverted the constitution. Rosen traces congressional legislation vs. Supreme Court decisions from John Marshall’s encounters with President Andrew Jackson to recent divisions of the court vs. anti-presidential immunity. Again, Rosen, currently president and CEO of the National Constitution Center, provides his own persuasive arguments. Have a comment or suggestion for Kale? Contact him at Kalehouse@aol.com.