Copyright Bloomberg

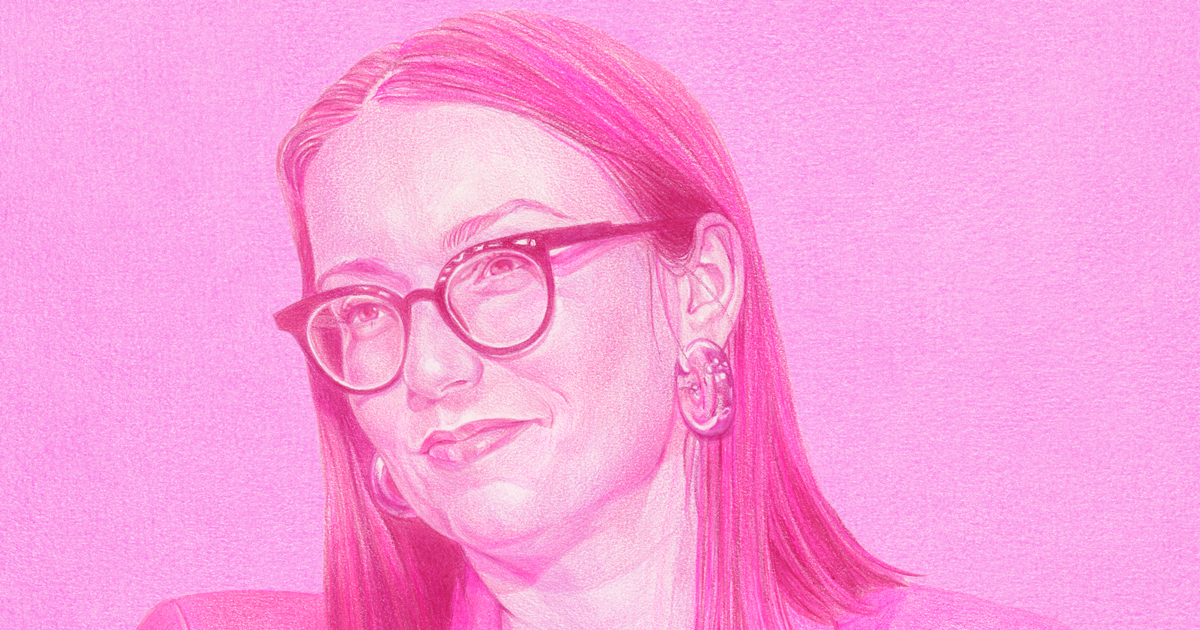

The Motherland author talks about reclaiming Russia’s women, the “demented family heirlooms” of Soviet trauma, and the country’s relationship with its chief decision-maker. Share this article Telling the story of a country through its women is an epic undertaking — especially when the country’s history includes totalitarianism, extreme violence and repression. It’s a task taken on by the Russian-American journalist Julia Ioffe in her new book Motherland: A Feminist History of Modern Russia, from Revolution to Autocracy (Harper Collins, October 2025). From Alexandra Kollontai — who laid the foundations of gender equality in the Soviet Union — to legions of women persecuted and abused over generations, Ioffe’s book weaves between notable figures airbrushed from Russian history and individuals who wouldn’t have thought themselves remarkable, including her own female relatives. Motherland also comes right up to the present day. Having spent more than a decade reporting from, and on, Russia for publications including the New Yorker and Foreign Policy, Ioffe says she has repeatedly been asked to explain the actions and motivations of Vladimir Putin. Motherland embodies her desire to show that Russia is much more than one person, let alone one man. To me, the book feels born of both love and despair for the country where Ioffe was born. Love, because it is a part of her through family members shaped by its tumult; despair, because she sees Russia as trapped in a cycle of authoritarianism and thaw, never a full spring. We spoke in Washington, DC, where Ioffe lives and works. Listen to and follow The Mishal Husain Show on iHeart Podcasts, Apple Podcasts, Spotify or wherever you get your podcasts. The Mishal Husain Show: Julia Ioffe (Podcast) This conversation has been edited for length and clarity. You can listen to an extended version in the latest episode of The Mishal Husain Show podcast. Motherland is an immense work — the story of modern Russia through its women, including the women of your family, because Russia is where you were born in the 1980s, in the time before Glasnost. 1 1 Ioffe was 4 years old when Mikhail Gorbachev’s “openness” policy began to relax censorship and release dissidents. In 1991, his successor Boris Yeltsin brought the Soviet Union to an end. I witnessed the chaotic period that followed when I lived in Moscow — Ioffe’s native city — in 1992 after having studied Russian at school. Yes. I actually was born in a country that no longer exists in many senses of the word — the Soviet Union — but also the emancipatory experiment it embarked on in 1917 vis-a-vis its women [is gone]. I’m keen to understand to what extent the stories of your grandparents’ generation, and those before, were told to you. There’s one moment in the book when you’re still in high school and your mother sits you down and reads from the poetry of Anna Akhmatova. She uses it to tell you about Stalin’s terror. 2 2 Anna Akhmatova (1889-1966) was a giant of Russian literature. Her poem Requiem, written in the 1930s, is about her suffering over the politically charged detention of her son. It was not published in Russia until the 1980s. Yes. The cosmic violence, the way it mangled Soviet, and then Russian, society forever. It was such a formative experience for the people who lived it and survived it, that their children and grandchildren were marked by it because of the family stories, because of the lessons of survival. Many of them, quite macabre, were passed down to us as demented family heirlooms. And your mother cries as she reads to you from the poem Requiem. I’m going to read two lines: “They led you away at dawn, I followed you like a coffin.” Even you mentioning it is making me clam up. I cannot read Requiem without bawling. It is so powerful. It’s like mainlining the tragedy of those years. It is an excruciating poem, beautifully so. There’s a part that’s very simple and it tricks you into thinking that it’s a nursery rhyme, but it’s devastating: “Эта женщина одна. Муж в могиле, сын в тюрьме, Помолитесь обо мне.” “This woman is alone. Husband in the grave, son in jail, Pray for me.” It’s that wrenching simplicity. 3 3 The translation is Julia’s own, from Motherland. The way she started quoting from the original reminded me of my time in Moscow, and the affinity Russians have with their literature, perhaps especially through adverse times. And it’s the story of millions. By the time Joseph Stalin died in 1953, 20 million Soviets had been through the gulag. About 3 million of them died there, of starvation, exposure [and] violence. About a million Soviets were executed without even getting to the gulag. 4 4 In The Gulag Archipelago, a definitive account of the camp system and wider repression, Nobel literature laureate Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn writes of the capacity of individuals to carry out extreme violence: “The line separating good and evil passes not through states, nor between classes, nor between political parties either — but right through every human heart.” It was a brutal time and the women suffered in a way that was unique to them. Most of the people arrested in the purges were men. Mostly, women were left on the outside with no information about what happened to their sons, their husbands, their fathers. Those [women] who were arrested, in addition to what the male prisoners suffered — privation, hunger, exposure, violence — they suffered sexual violence. They had to deal with the aftereffects, either by figuring out how to have an abortion in the gulag without any medical treatment — there are some pretty gruesome descriptions in the book of how women managed to do that — or they carried the babies to term, also with tragic consequences. So many of these babies died in the gulag, in their own kind of horrific internment conditions. I’m going to pick a few stories of individual women from the book, conscious as I do so that this is a limited choice from a massive tapestry. But tell us about Alexandra Kollontai, who was at Lenin’s side during the Revolution and lays the framework for women in Soviet Russia. 5 5 1917 was a year of revolution in Russia, as the Romanov dynasty was deposed and the Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin, then established the world’s first communist state. Kollontai was born into privilege in 1872 before becoming a Marxist and Lenin’s Commissar for Social Welfare, which Ioffe says makes her the first woman in the world to hold a cabinet position. The Bolsheviks were by far the most egalitarian of all the underground opposition to the tsar. Alexandra Kollontai really fleshed out these ideas about what would be needed for women to be truly emancipated, truly equal to men in a future utopian, egalitarian, socialist society. In 1918, she institutes some incredibly radical reforms. Women are given the right to no-fault divorce, paid maternity leave, access to free higher education, child support — even for a child that is born out of wedlock. In 1920, the Soviet Union legalizes abortion and makes it free and relatively safe for Soviet women. And yet, she would have bristled if we called her a feminist. For socialists, class comes above everything. You studied Soviet history here in the US. Did you know about Kollontai? No. She was written out of history by the Bolsheviks. They were radically egalitarian when they were underground and they weren’t in charge of anything. The second they took power, the men [got] the real positions of power. Also, the history was written by men, and they don’t take these issues seriously as a rule. For male historians, male journalists: War, economics, big factories, pipes and guns are important. I don’t know if that reflects your experience in the profession, but in my experience, you have to write about those topics to be taken seriously That’s why I was reluctant to do a book about Russian women, I had to be talked into it. I was like, That’s not serious. 6 6 Motherland was inspired by Ioffe’s agent noting that many women in Ioffe’s family — doctors, scientists, a chemical engineer — held roles that few American women held in the same period. I think she’s right that women can still be negatively perceived if they don’t tackle tough, traditionally male topics; conversely, I appreciate the men who have not shied away from writing about sexual violence. In 2022, Antony Beevor did this on the Red Army’s actions in Berlin in 1945. I want to bring out some other women from Motherland. One is really tragic and painful: Valentina Drozhdova, who was raped by Stalin’s secret police chief Lavrenty Beria — one of many women and girls he abducted and assaulted. How hard was it to uncover a story like that? Very, very, very hard. On one hand, people knew anecdotally that this was happening, even where it was happening. People knew where Beria lived, that he cruised the streets of Moscow looking for pretty young girls that he brought back and raped. If they had husbands, he would take care of that. But when I went to find this in the historical canon in the West, it was usually relegated to a footnote — salacious, prurient and unserious. It’s about sex and so it’s not serious and it’s kind of gross and let’s not dig into it. Women would write to Beria on behalf of their fathers, their husbands, and say, I know he’s innocent, can you let him go? His lieutenants would find out if the woman was pretty. If she was, she’d be called in on the pretense of Beria helping with her case, only for the tragic, [the] inevitable, to happen. Beria eventually impregnated Valentina at 17. When she was in labor, he called her at the hospital and said, I’ll give you whatever you want. Because she was just a child herself, she asked for a bicycle. [Valentina] died in 2014. That means she was alive when I was living in Moscow. I could have found her, I could have interviewed her — but I was busy writing about Putin, and not thinking about “unserious” things like sexual violence as a tool of the state. I totally missed it. I massively regret it to this day. 7 7 Ioffe’s grandmother Emma first mentioned the dark history of Beria’s house during a walk through Moscow. As a girl, she and her friend would avoid it — everyone knew that Beria abducted women off the street. Drozhdova was one such girl, spotted while she was out buying bread in 1949 and lured inside on the pretext that Beria would help her sick mother. Instead, he raped her and held her captive for three days, later forcing her to return under threat that her mother would be sent to the gulag. Is Motherland a response to being asked so much about one man, Putin? God yeah, absolutely. I’m just so sick of talking about him. On one hand I get it — he is the sole decision-maker, effectively, in a dictatorial state. But I know from my own experience that Russia is bigger and more complex than that. Even a dictatorship is multifaceted when you start looking closely at it. Dictator to dictator, the periods were different. This was one of the reasons I wrote the book — to take time out in 2017, when all of Washington was obsessed with Donald Trump and his relationship to Vladimir Putin. I was like, I just never want to talk about Vladimir Putin again. We’re there again, though, with Trump and Putin. Yes. I hope you’ll forgive me if we come back to that. But Putin does feature in Motherland — Lyudmila Putina, his now ex-wife, is one of your characters. Tell us about finding an interview she once gave about him. It was quite a feat to track it down. In 2002 [a Putin] biography came out, supposed to be the first of several volumes. Clearly resentments had piled up over the first two years of his presidency. [Putin] didn’t even tell her that he was going to become president — she didn’t know to turn on the TV to watch Boris Yeltsin hand over to her husband. She pours her heart out to this interviewer, tells him what a horrible boyfriend Vladimir Putin was — a terrible fiance, an even worse husband. I have no idea what happened to that author, I can’t find him. I had seen people refer to this book, but trying to find the original source was almost impossible because the book was out of print. Even though you can get any Russian book pirated 75 different ways online for free, this one was nowhere. It had clearly been purged from the web. I found one copy on Amazon for about $200. It was a treasure trove of information about — pardon my French — what an a**hole Putin was. What a tyrant he was at home, before he became a tyrant to the rest of the world. After emigrating with your parents, you returned to Russia in 2009 as a journalist — to the same Moscow apartment block where you lived growing up. I lived on a foldout couch in my grandmother’s apartment — what had originally been my great-grandmother’s apartment. I had a blast, some of the best years of my life. Russia was in a temporary thaw under [President Dmitry] Medvedev. Media outlets were sprouting up and there was this freedom to speak, to think that maybe some of the freedoms and liberties Putin had taken away during his first two terms in office between 2000 and 2008 could be returned. It was this moment of incredible excitement. 8 8 Putin became Russia’s acting president on New Year’s Eve 1999, when Boris Yeltsin resigned. After serving two terms, he groomed Medvedev to succeed him as president in 2008, while he became prime minister. Four years later, Medvedev stood aside, allowing Putin to stand as president again. And people getting rich. The riches are insane. I mean, I had never seen wealth like this, not even living in New York. Westerners don’t flaunt their wealth quite the same way. I also noticed that women had changed — they weren’t like the women in my family. It was like we left 20 years beforehand and were this weird extinct species preserved in amber back in the US. Whereas post-Soviet women had evolved to be these oligarch hunters, essentially wanting rich husbands. Do you see parallels to today and the “trad wives”? Yes, except the trad wife thing here in the US is much more intense and has this kind of homestead aspect to it. [Imitates American influencer] I woke up this morning and my husband was craving gum, so I decided to make it from scratch — I think people will know which influencer I’m talking about. The women in Russia who wanted to marry rich and stay home, didn’t want to have eight kids and cook all their meals from scratch. They wanted to just live for themselves and get their nails done. How did you fit into that? Because you’re a young woman at that time. You’re dating. I didn’t [fit in]. Coming from the West, with my parents’ ideas about what it meant to be a woman — in my family, it was just assumed that you go to college — I get to Russia and women just want to wear crazy heels and are made up all the time. Cosplaying femininity, and just constantly hunting for men. In that context, I felt like a third asexual gender or a talking dog that didn’t fit in at all. I think Russian men found me bewildering. Get the Bloomberg Weekend newsletter. Big ideas and open questions in the fascinating places where finance, life and culture meet. Sign Up By continuing, I agree to the Privacy Policy and Terms of Service. Did they see you as Russian? No. They saw me as very American and a feminist, which was a bad word — still is a bad word. I’ve been told by a friend who runs a publishing house in Moscow that they can't translate my book because feminist is now essentially a banned word, and it’s in the subtitle. The most disappointing part is Western men who were highly educated — who had gone to the Harvards, Stanfords and Cambridges — went to Russia and were so happy to throw feminism overboard, because they had these women who were like, I’ll just be the traditional very subservient, ultra-feminine woman for you. You’re in charge and I’ll do anything you say. And then of course they would wake up to realize, I think I’m paying my girlfriend an allowance, but I’m not sure. What did your parents make of you coming back to Russia and immersing yourself in the study of the Soviet Union? They left for the United States in 1990 because they were fearful of anti-Jewish pogroms. Yes. My mother had heard the widespread rumor that to celebrate the 1000th anniversary of Russia becoming Christian, there would be pogroms — that the police were handing out names and addresses of Jews. Even though nothing ultimately happened, it was believable. She gave my father the green light to start the immigration process, but he had wanted to leave forever. He hated the system. I decided to study Soviet history — Marxism, Leninism, all this stuff that they had been forced to learn, hated, and wanted to leave behind. They were horrified and couldn’t understand why I was doing it. I want to talk about one of the people you got to know when you went back to Russia, Alexey Navalny. Tell me about meeting him for the first time. He was an up-and-coming blogger who was writing about corruption and the way Putin was using state corporations to funnel money away from taxpayers to the pockets of [his] friends. People were taking notice of him because there was a thriving blogosphere. This was a period of relative freedom before the FSB had figured out the internet, let alone how to police it. I met him for lunch and immediately it felt like what it must have been to meet a young Bill Clinton or a young Barack Obama. The force of personality, the force of conviction — he had his own gravitational pull. It was intoxicating, unlike anything I had seen before, and I had met Boris Nemtsov and other opposition leaders. I mean, we had big differences and would get into fights sometimes. 9 9 For the podcast version of this conversation, we played Ioffe a clip of Navalny speaking in a BBC interview in 2017. Hearing his voice, tears came to her eyes. Navalny was 47 when his death in an Arctic prison was announced in February 2024. I think you told him at one point you thought one of his speeches was antisemitic. Well, I tweeted it, and my phone rang, and it was him yelling at me. He was talking about oligarchs, and specifically mentioned oligarchs who had recognizably Jewish names. 10 He was very imperfect, as all humans are and all politicians who aspire to the presidency of a country. But he was an incredibly brave, charismatic person. 10 Ioffe is referring to Navalny’s speech at a 2011 nationalist rally, in which he also said, “This is our country, and we have to eradicate the crooks who suck our blood and eat our liver.” She characterizes this as “old-school” Russian antisemitic imagery, but notes that his views would evolve as his campaign professionalized. When he was killed, it felt like the last shred of hope that any of us had for a better Russia post-Putin went with him. It felt like the Russia I was a part of when I moved back — this young, democratic, vibrant, pro-Western Russia — he was the last living representative of that. By the time his death was announced in 2024, he’d spent three years in detention. The way he died in that prison in the Arctic Circle, it was so tragically in line with so many deaths in your book — the gulag, the extreme depravity, the senseless tragedy. One very important institution that transmitted the values of the Russian state over the centuries — across an imperialist vision, a socialist utopian vision, and today’s nationalist vision — is the penal system. You write in Motherland that part of what undoes Navalny is the Ukraine war. In 2022, when the full-scale invasion happened, many of his base of educated Russians wanted to leave the country. Do you think Russia can sustain this war in Ukraine? It will try as long as possible. I think the turning of World War II into a state religion, a state cult, allows Putin to say, Look, we defeated Nazism by laying down 27 million Soviet soldiers. The war nearly destroyed our country, but we won. Right now, Russia has lost maybe a million men [in Ukraine] to injury and to death. The message is, That’s a fraction of the cost. I think in Putin’s most recent negotiations with Trump, first he tried to outmaneuver and say, Forget about Ukraine, let’s just normalize a relationship between Russia and the US and then you, your family, and American companies can come in and do business in Russia and make an absolute killing. But he can’t let go of his fixation on Ukraine. He is willing to sacrifice everything, because he has made this war existential. I think he understands that if Russia loses the war, or is seen to lose the war, then he is a goner — he cannot last on the throne. Even if he were to leave power, his successors will feel the need to carry it on. I think a lot about the US and the Iraq War, where even Democrats like Barack Obama, who felt that Bush’s invasion was wrong and criminal, had to keep fighting because Americans didn’t want to lose. I want to ask you about your work today, covering Washington. How has it been as a journalist, given the ways in which the Trump administration has tried to restrict or sue the press. What’s your assessment? 11 11 Ioffe is Washington correspondent for Puck, a digital media company founded in 2021 whose the writers are also partners in the business. Donald Trump has been able to do, in less than a year, what it took Vladimir Putin two decades to do, in certain cases. The speed at which he has hollowed out American institutions — the courts, the legislative body, every check and balance imaginable, the way private industry has bent the knee, rather than risk their profits — forgetting, by the way, that more than half the country doesn’t like this — makes me disappointed in my American compatriots. In all those years I was reporting on Putin, anytime [he] did something restrictive, authoritarian, I would be asked to come on TV or to write a piece. People would say, Why aren’t Russians out in the streets protesting and overthrowing him? Can’t they see how terrible it is? Can’t they see he's a dictator? Surely young people, college students, hate this? I want to ask all of them, Why aren’t Americans in the streets, demanding answers and demanding a change? Not protests by appointment, with funny posters, but real protests. Why aren’t we holding our corporations to account, our Congress to account? Donald Trump jokes that he is the speaker of the US House of Representatives and the president. He’s essentially dissolved Parliament. If I were a foreign correspondent here, trying to explain this for an audience back home, that’s how I would write it. Is this a version of authoritarianism? Absolutely. For many of us who have seen this movie before in Hungary, Russia, China, Venezuela, we were sounding the alarm starting in 2015-16. I would not be surprised if [House Speaker] Mike Johnson refused to seat Democrats who win seats in the November midterms in 2026. I would not be surprised if, after those midterms, we are effectively a one-party state in the way that Hungary or Russia are one-party states, even though other parties still exist on paper. I saw my Russian colleagues saying, Putin wouldn’t do that. He did A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H, but he wouldn’t do I and J. And then he does I and J, and they’re like, Well, he wouldn't do M, right? I think it’s time to open our eyes and see where this is going, and stop pretending that somebody who has gone this far won’t go one more step, two more steps, three more steps. To close, Julia, this is the Weekend Interview. Can we go back in time, to your childhood in Soviet Russia, and your weekends then? Especially as a Jewish family, the Sabbath, in a state where religion is frowned upon. We didn’t know what that was. [I was] growing up with parents who hated the Soviet Union, but were still very much creations of the Soviet Union, in terms of militant atheism. Do you think in Russian, do you dream in Russian? Only when I’m in Russia. I haven’t been back since just before the pandemic, and I don’t know when I’ll ever go back. I can’t imagine it being safe to go back for a very long time — definitely not while Putin is alive, and I think Putinism will live on after him, the same way Stalinism lived on after Stalin, for about 40 more years. Do you miss it? Is there a sense of loss? It’s a massive sense of loss, in the same way that hearing Alexey’s voice brought tears to my eyes, because his death was a severance of a thread tying me to that place. So many people have either left or died or been killed. So many beloved institutions and places have closed. I think even if I were to go back now, it would be a totally alien place. Is there any source of hope that you have for Russia? Nothing is forever, but Russia certainly does have a pattern. This will lead to a period of thaw and liberalization, before another snapback and backlash. That’s just how Russia does things. So I’m hoping to at least catch that little thaw in the future. Mishal Husain is Editor at Large for Bloomberg Weekend.