Copyright The New York Times

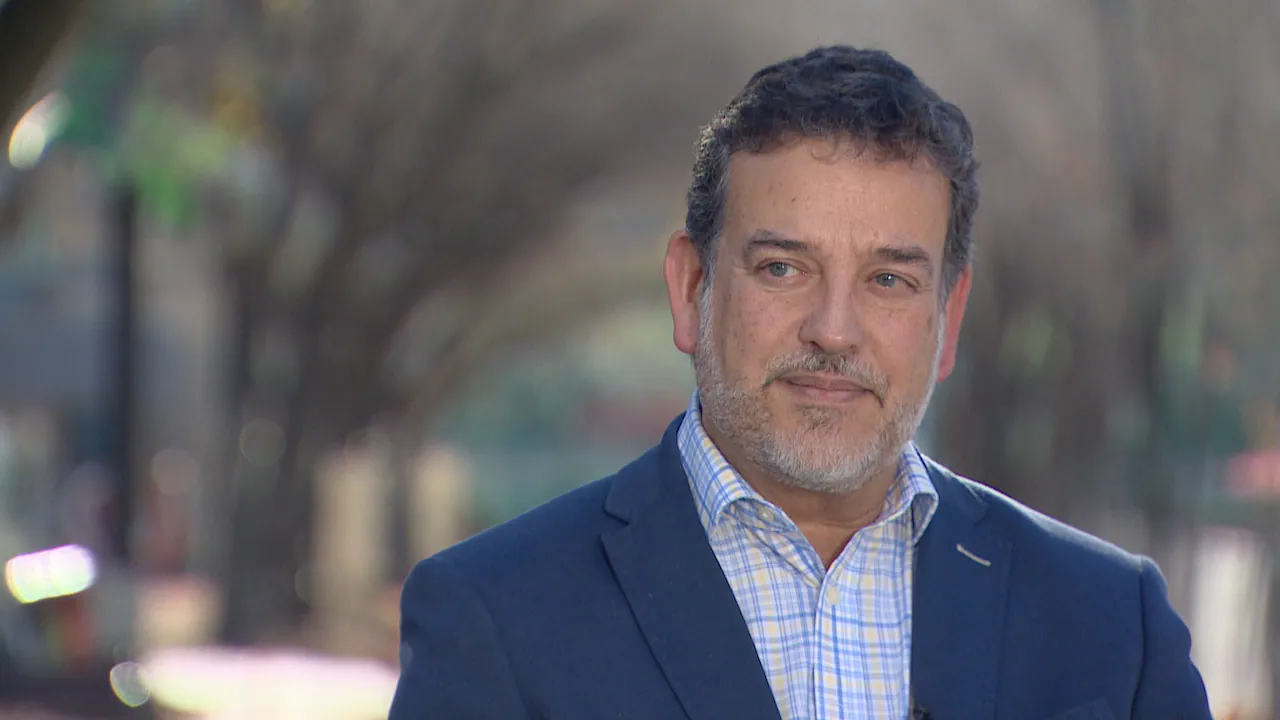

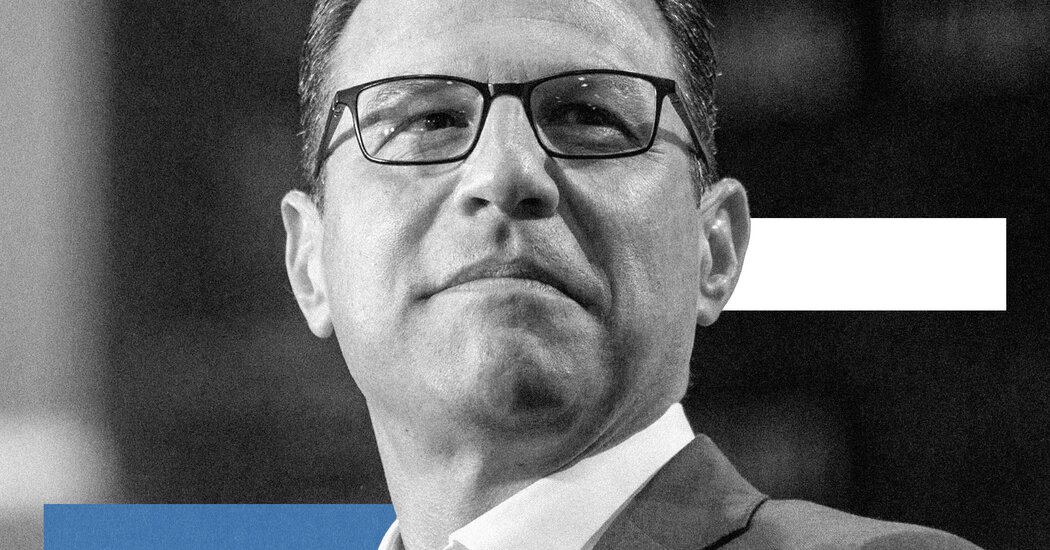

This essay is the fourth installment in a series on the thinkers, upstarts and ideologues battling for control of the Democratic Party. A cardboard cutout of a presidential candidate could win California on the Democratic line and another 15 deep blue states. The question Democrats need to answer, the question that matters for the future of the Democratic Party and quite possibly for the future of democracy in America, is what kind of Democrat can win Pennsylvania. As it happens, we already know the answer. His name is Josh Shapiro. In his last three elections, beginning in 2016, Pennsylvania’s governor has drawn more votes than anyone else running in the state — presidential candidates, Senate candidates, other candidates for statewide office — and outperformed other Democrats in the exurban and rural areas where the party is struggling. Centrist Democrats govern several of the states that President Trump won in 2024, including Michigan’s Gretchen Whitmer, who won office on a promise to “fix the damn roads,” and Kentucky’s Andy Beshear, who has championed a bipartisan “Team Kentucky” approach to attracting corporate investment to the state. Mr. Shapiro intrigues me because, in an era of widespread distrust in government, he has become the most popular politician in the nation’s most important battleground state by insisting that government can work. He has a record of delivering clever political compromises, and he’s good at making centrism sound urgent. His political persona is a constant performance of vigor. As he reminds Pennsylvanians at every opportunity, he gets stuff done. His most celebrated achievement is reopening a collapsed highway in just 12 days. Tuesday’s election results have supercharged the debate among Democrats about whether the road to political recovery runs toward the middle or the left. The reason the argument persists is not because the answer is unclear but because, for many Democrats, the clear answer is unpalatable. The party will not return to the White House, nor reclaim Congress, until it learns to embrace centrist politicians like Mr. Shapiro. Zohran Mamdani’s victory in New York does not demonstrate the viability of progressive candidates outside of a few big cities and coastal states. Nor can Democrats solve their problems by wrapping the same ideas in better paper. The party has marginalized itself so thoroughly that even Mr. Trump’s unpopular presidency isn’t doing much to make Democrats more popular. Everything Democrats want to accomplish is downstream from figuring out how to persuade voters in places like Pennsylvania — and in a bunch of places where the Democratic brand is held in even lower regard — that the party deserves another chance. Mr. Shapiro’s recipe is a plausible basis for the party’s renewal. Democrats are the party that believes in government; they have to show that government can work. They have to deliver the stuff they’ve already promised: education, security, opportunity. As Pennsylvania’s attorney general in 2020, Mr. Shapiro repeatedly battled Mr. Trump’s legal assaults on the integrity of the state’s election results, delivering the kind of confrontations that many Democrats crave. But the way to beat Mr. Trump is to show Americans that you have a better alternative. Mr. Shapiro’s version of the Democratic Party is more patriotic than the G.O.P. and, in some sense, more conservative. It is a party that wants to improve public institutions rather than blowing them to smithereens, and to carry forward the basic elements of the American experiment: liberal democracy, a pluralistic society, free markets regulated in the public interest. History teaches that people will readily sacrifice democracy to regain a sense of safety and stability. Mr. Shapiro recognizes the urgency of convincing people that democracy is still the better bet. One of the most durable patterns in American politics is that voters trust Republicans more than Democrats to fight crime and deliver economic growth. It’s no coincidence that on a recent Friday, Mr. Shapiro was in Pittsburgh to talk about crime and economic growth. Standing on a bluff above the Allegheny River, he delivered a progress report on a package of investments in downtown Pittsburgh, which loomed photogenically behind him. It was a surprisingly hot day, and much of the crowd had retreated under a canopy. Aides handed out water bottles to the municipal workers who had been rounded up to stand with Mr. Shapiro. The governor, dapper and trim, hair slicked back, grin like a Cheshire cat, didn’t seem to notice the heat. He looked as if he was having fun. “These projects are moving fast,” Mr. Shapiro told the cameras. “We are not wasting any time.” The Pittsburgh plan is a relatively modest intervention into the city’s fortunes, but it’s a good illustration of Mr. Shapiro’s political formula. The first rule of improvisational comedy is “yes, and ….” You accept what the last person said, and then you build on top of it. Mr. Shapiro takes a similar approach to forging political compromises. He’s in favor of more money for the police and for public defenders. He has pushed to increase funding for public schools and to provide school vouchers to parents. He has delivered some high-profile wins for businesses, notably a cut in the state’s corporate tax rate. He also has retained strong support from unions by backing a higher minimum wage and vowing to block any right-to-work legislation. His Pittsburgh plan is a standard set of economic development and public safety proposals, with some distinctly Democratic touches: subsidies for the redevelopment of office buildings and housing for the homeless; more police officers working downtown and increased collaboration with social services agencies. A second tenet of Mr. Shapiro’s approach is telling people, repeatedly, what he is doing to help them, and that he is doing it as fast as possible. In June 2023, a tanker truck caught fire underneath an elevated section of Interstate 95 in northeast Philadelphia, causing a portion of the highway to collapse. The road was expected to be closed for months, but Mr. Shapiro declared a state of emergency and approved a plan to fill the area underneath I-95, allowing rapid construction of a temporary replacement on top. He went before the cameras and promised to reopen the highway in two weeks. It reopened in 12 days. Government often doesn’t work because the left cares more about procedures than outcomes, and the right opposes the outcomes. One side wants to start building a modern railroad between Los Angeles and San Francisco just as soon as all the paperwork is done; the other side wants to kill the project. Neither approach helps to move people between the cities. Mr. Shapiro rejects both the proceduralism of the left and the nihilism of the right. In a recent conversation, he told me that he was “someone who believes the government can be a force for good in people’s lives.” A substantial majority of voters no longer trust government to pursue big projects, and Mr. Shapiro was quick to add that he understands and shares the frustration with government in its present shambolic condition. “Our institutions are important, but need to be reformed,” he said. “Our fundamental responsibility is to show our work and deliver for our people — to get stuff done.” (Mr. Shapiro often uses a different word in place of “stuff.” He told me that he was censoring himself because he was talking to The Times.) On his first day as governor in January 2023, Mr. Shapiro signed an executive order eliminating college degree requirements for most state jobs. It was an effort to help lower-income Pennsylvanians — and a corrective, he said, for his party’s elitist tendencies. “For the last more than a decade, the Democratic Party has been saying to people that you’re not really successful unless you go to college,” he said. “I think that’s offensive.” The best case for Mr. Shapiro’s brand of politics is that it works. The last time he lost an election was in 1990, when he was an 11th grader at a high school outside Philadelphia and he finished third in the race for student body president. After graduating from Georgetown Law and working on Capitol Hill, Mr. Shapiro returned to Pennsylvania in 2004 and won a seat in the state House. In 2012 he traded that job for a seat on the board of commissioners in Montgomery County, a Philadelphia suburb, and in 2016 he became the state’s attorney general. His defining chapter in that job was his defense of the integrity of the 2020 election. He repeatedly beat back the attempts by Mr. Trump’s campaign to make voting more difficult, and then to prevent the counting of votes that already had been cast. In 2022 Democrats regarded him as the obvious choice to run for Pennsylvania governor, and he won in a landslide. Mr. Shapiro’s most immediate political challenge is running for re-election next year, but it may not be much of a challenge. Polls shows that he’s more popular today than when he was elected. His approval rating stood at 60 percent in a poll published last month by Quinnipiac University, with 28 percent disapproving. When I asked Mr. Shapiro if he is interested in taking his brand of politics national, he demurred in the way that a practiced politician does when he is keeping his options open. “I’m humbled and flattered that you view the way in which we govern in Pennsylvania as a model for others,” he said. There are some obvious reasons to worry about his national appeal. He is a career politician in a country that disdains the profession, a proponent of better government in an era defined by bipartisan suspicion of the state, and a practicing Jew in a nation that prefers presidents who are at least nominally Protestant. Mr. Shapiro has angered some Democrats by backing school vouchers and defending Israel, although he has criticized its current government. And Pennsylvania — while similar demographically to swing states like Michigan and Wisconsin — is less racially diverse than the United States as a whole, and in particular has a relatively small share of Latinos. Perhaps his biggest challenge, certainly in pursuing the Democratic nomination, is simply that a lot of progressives don’t want a centrist. They see the party as defined and held together by its commitments to change; they believe it is those commitments that motivate people to vote for Democratic candidates. “Progress is our heritage,” Ted Kennedy declared in his 1980 speech conceding the party’s nomination to the centrist candidate, President Jimmy Carter. “What is right for us as Democrats is also the right way for Democrats to win.” For progressives, it is always 1980, always on the cusp of that fateful choice between integrity and tepid centrism. Healthy political parties, however, cannot be solely progressive or conservative. They must be both. They necessarily embody a set of judgments about what to preserve and what to change. Democrats may prefer to describe themselves as “conservationists” committed to protecting the natural environment or “preservationists” opposed to development that disrupts established communities. But those are fundamentally conservative projects, devoted to protecting what already exists. Almost a century after Franklin Roosevelt created Social Security, it is no longer progressive to defend the program. It will soon be older than all of its beneficiaries. The first great exponent of modern conservatism, the Anglo-Irish politician Edmund Burke, would have had no trouble recognizing Mr. Trump’s Republican Party as embodying the political tendencies he regarded as most dangerous. Burke, writing during the French Revolution, saw conservatism as a bulwark against radicalism, a defense of society against the ravages of men who had lost their moral compasses and were wielding power almost as an end in itself. He would have loathed Mr. Trump. I think Burke also would have recognized Mr. Shapiro as something of a kindred spirit. Burke understood that change was necessary. States that lacked the capacity to change, he wrote, also lacked the capacity to survive. What he argued, however, was that societies should address problems by improving existing institutions rather than knocking them down. When I put this to Mr. Shapiro, he was understandably reluctant to embrace “conservative” as a description of any part of his politics. “I do believe in the institutions,” he told me, “but they’ve got to be reformed so they can work for the people.” Call it what you will: Mr. Shapiro’s challenge will be to persuade people that the best way to address our problems — the best way to make America great again — is to double down on the things that got us here in the first place. Not incidentally, these are also the things that voters routinely say they care about most. We were the best educated nation in the world. We need to invest in education. Our infrastructure was the envy of the world. We need to invest in infrastructure.