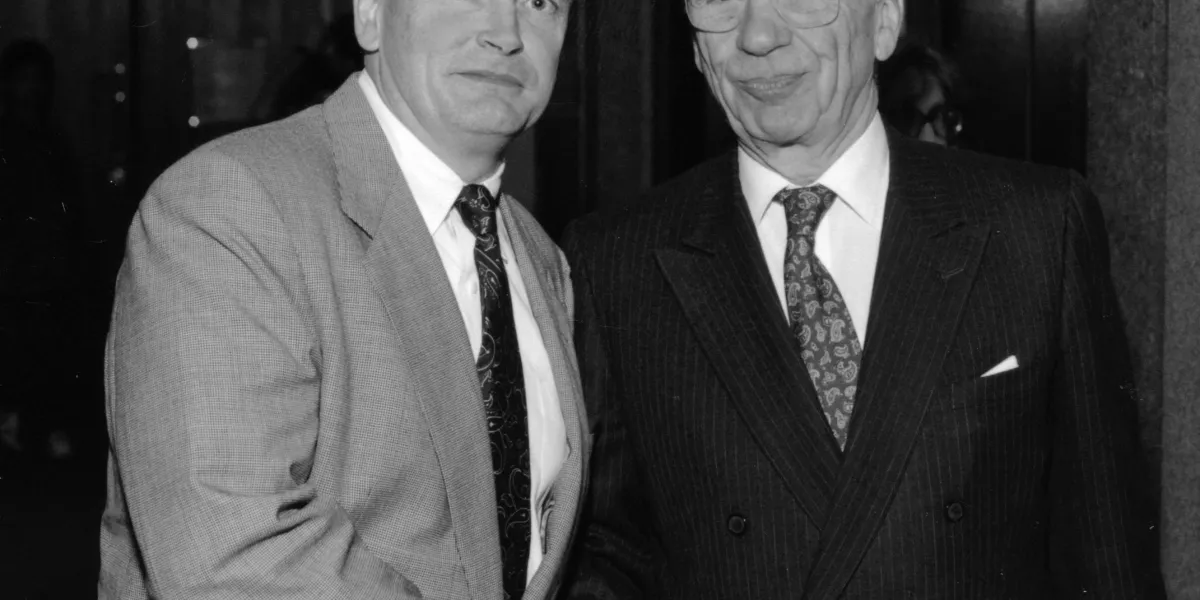

John Malone on his friendship with Rupert Murdoch: He remained a gentleman, even when blindsided

That trust can be damaged by a single phone call. Or by the lack of one, and that is what happened to Rupert and me in this next go-round.

On Tuesday evening, November 2, 2004, my wife and I were watching coverage of the election returns for Republican George W. Bush and Democrat John Kerry when the phone rang. The caller surprised the hell out of me.

Our Merrill Lynch contact in Sydney was calling me back to confirm an earlier call in which he told me that, inexplicably, a big block of News Corp. voting stock, the kind of shares that Rupert and his family owned, was coming up for sale on the Australian stock market. As he had asked earlier, were we interested in buying it?

News Corp.’s business properties were becoming more valuable than Rupert’s holdings in Australia, and he had decided to delist the company’s stock from the equivalent of the S&P 500 on the Australian exchange and have it join Nasdaq in the U.S.

Moving News Corp. to Nasdaq forced Australian index funds to sell their shares, including a large block from the Australian Index Fund, which had to auction off its stake by the end of the day under its rules. As the Merrill caller told me: “The entire holding of News Corp. will be liquidated from this fund. Those are the rules. So, if you’re interested in buying some of this, have somebody there with the authority and the wherewithal to bid for it.”

My company Liberty already had built up a 9% stake in News Corp. with non-voting shares and was the largest single shareholder in the company after the Murdoch family, which held 27%. This was a rare opportunity for us to own an even bigger stake by acquiring voting stock—on the open Australian market.

I had always known in the back of my mind that at some point down the road, Rupert and I would sit down, and he would swap us out and trade some attractive assets he owned for our stake in his company. At the time, I had no idea why so much precious voting stock in Rupert’s company was coming up for grabs, and neither did Liberty’s CEO, Dob Bennett, but I knew a cheap stock when I saw it. I advised Dob to buy the shares in the Sydney auction, telling him, “If News Corp. or the Murdoch family show up to bid for it, stand down. If no one from the Murdoch family shows up, then go ahead and bid for it.”

“How much do you want to buy?” Dob asked me. “It’s gonna be quite a bit.”

“All of it.”

The deal somehow turned me into Darth Vader, parked on Rupert’s lawn with cannons pointed

Liberty Media entered an open auction for News Corp. stock, trading 21 million non-voting shares plus cash in exchange for a 9% voting stake. In 2004, Liberty increased that stake to 17%, making it the second-largest voting shareholder after the Murdoch family, which held 30%.

To me, this was a continuation of our strategy to accumulate News Corp. stock on the open market because I genuinely regarded News Corp. as undervalued and I trusted the leadership. If we were ever going to swap out with Rupert, it would be better to have the voting shares.

As I saw it from Rupert’s point of view, he was low on cash, and stock was the one asset he had in his company for doing deals. And Liberty was a friendly company with a lot of firepower.

I knew that in any transaction with any company, voting equity will have a greater dollar value, and greater psychological value, than nonvoting stock. This especially was true for a family-controlled company like News Corp., where it was especially important to Rupert Murdoch to retain control and hand his company to his two sons, James and Lachlan.

The statement from Liberty was succinct, or so we thought: “News Corp. is one of the few truly global media companies, and we are very pleased we were able to leverage our substantial equity interest in News Corp. into a larger equity and voting stake.”

News Corp., officially, at least, said it welcomed the investment. “In our view this is another sign of confidence in our company’s health and future strategy by Dr. Malone,” a News Corp. spokesman told AFP.

Still, the media swirled with wild speculation about Liberty’s intentions, eagerly suspecting we were plotting a takeover with the second-largest voting stake. Looking back, I made a critical mistake, especially when dealing with a friend: I failed to be absolutely clear about my intentions. Having failed to call Rupert when we first heard about the stock coming up for sale, I should have called him after the news broke to tell him what had happened. But I didn’t. And so the speculation that we were going to make a move on his company only intensified.

An article in The Independent described me as Darth Vader in the opening sentence and said I had “parked [my] tanks on the lawn of Rupert Murdoch, their cannons aimed squarely at Murdoch’s own media empire.” The story went on to say that “it is not unreasonable to wonder if he is in the first phase of an all-out campaign to acquire News Corp., owner of The Times, BSkyB, Fox Television and countless other assets for himself.” This had to have unnerved Rupert. Publicly, he was unflappable. Was he concerned? a reporter asked him.

“No, not at all. I think it’s an endorsement of the company. I say that quite sincerely. I’m not losing any sleep over it.”

It wasn’t hostile, but it wasn’t friendly

For a few days, he didn’t return my phone calls, and I couldn’t blame him. We were both trying to figure out what had happened.

Someone must have made a mistake for a family dynasty to allow that much stock to go on the open market. I knew from his people talking to our people that Rupert was pissed, but I also knew that he was a hell of a lot more pissed at his own people.

But at that point, a deep, primal defense instinct, honed over decades, had awakened in my old friend, and there was little I could do to put him at ease. Rupert then took some very public defensive measures, rallying allies, including a Saudi prince who moved to acquire 5% of the stock on the open market.

And yet Rupert never called me screaming, demanding answers. He never attacked me or Liberty publicly. He was, always, a gentleman, and that is important to me in business dealings.

Of all the companies in media where we owned sizable stakes, including Discovery, QVC, and Starz, the News Corp. stake was Liberty’s most valuable asset. I had no intention of taking over, or even threatening to take over. I knew once we had that block of stock, we would be able to work something out with Rupert that was mutually beneficial. As chairman/CEO, it was my obligation to increase the value of Liberty’s shares.

When I finally did talk to Rupert a few days later, it wasn’t hostile, but it wasn’t friendly. He didn’t cast blame or chide me or say I should have told him. It was simply, okay, these are the facts, what are we gonna do about it?

I expressed to him that we would have stayed out of it if he wanted to buy the big stake, but we saw no one from News Corp. at the auction, and we loved his company, so we bought it.

“Rupert, we’ve always had great relations. There’s no need to go into panic mode.”

Then I did what I could in the press to dispel any rumors of hostile intentions and show support for Rupert. We put out a statement saying News Corp. was “the best run, most strategically positioned vertically integrated media company in the world.” Liberty CEO Robert Bennett would later reaffirm the statements: “We are a large happy friendly shareholder.”

The poison pill

The press fed the intrigue, and five days after the news of our stock purchase broke, Rupert unveiled his board’s plans for a poison pill, specifically aimed at preventing me from increasing my stake further. The “poison” is different in each pill; with this one, if Liberty were to purchase any more shares, it would trigger a plan letting existing shareholders increase their shares at half price, making a takeover by Liberty all but impossible.

He was assuming that we were playing with his legacy, and he didn’t like it. The company said the poison pill was a precaution, and Rupert was doing exactly what I would have done had I felt threatened—protecting all shareholders from a takeover without getting paid a premium.

So we scheduled a series of meetings. Rupert and his sons, James and Lachlan, flew out to see me in Denver, and we met in a conference room at Liberty Media. I reassured them that we were happy, passive investors. Maybe we could do something creative here. There might be some assets they would like to swap for some of our News Corp. shares. Or if this was too much, maybe we could discuss a way to take us out over time.

They wanted to talk about a trade. And that is when Rupert Murdoch offered to swap us DirecTV.

James Murdoch, who was running Sky at the time, was concerned about the future of the satellite business and the fact that it lacked the two-way, interactive capacity of cable broadband networks. Cable operators were offering the Triple Play—voice, video, and data over one line—while satellite looked to be limited to a future as a robust one-way system with minimal internet delivery.

In the fall of 2006, we finally shook hands on a deal. I agreed to swap Liberty’s 19% voting stake in News Corp., valued at $11 billion, in return for Murdoch’s 38% stake in DirecTV, valued at roughly $7.4 billion, plus three regional sports networks owned by News Corp. and $550 million in cash.

All’s well that ends well

In the end, it worked out extremely well for us both.

The transaction gave Rupert the one thing that he cared most about—family control of the company. In redeeming the shares, he popped from 28% of the vote to a virtually unassailable 42%.

For Liberty, and for me, personally, this was the apex of three decades of dealmaking with Rupert Murdoch, one that would even up the ledger between me and an old friend and respected competitor.

Life is like that. Sometimes you have to experience a setback or a surprise to change your way of thinking. I look back and wish I had done some things differently, but I know the mistakes I made are an important part of what I learned, and they helped shape my thinking and make me a better person.

These days Rupert and I still talk, and now and again we still compete for the same prize. Always, though, we operate with the same decorum and respect that are part of our implicit agreement that we are going to play to win but not at the cost of our principles or reputation.

Liberty Global jumped into the ring against BSkyB in the UK in 2013 when we bought UK pay-TV company Virgin Media for $23.3 billion. Three years after that, we saw an opportunity for Formula One, owned by a consortium of companies led by CVC Capital Partners and run by longtime CEO Bernie Ecclestone.

We saw Formula One as an interesting turnaround proposition. Eyeing the field, we compiled a short list of our possible rivals in a bidding war, and the top three were Apple, a Qatari businessman, and my old friend Rupert Murdoch.

In late 2016 I got another call from Rupert, who this time told me, “John, I guess you know the boys [Lachlan and James] are going to be bidding against you on this. I don’t know why they want it, but I thought you ought to know.” It was a gentlemanly thing to do.

In the end, Liberty was willing to pay more, outbidding News Corp. and agreeing to $4.4 billion for a 35.5% stake in Formula One in January 2017, which valued the entire enterprise at around $8 billion including debt. We brought in one of Rupert’s most trusted executives as Formula One’s new chairman, Chase Carey, former executive vice chairman of 21st Century Fox.

Some time later, Rupert made another call to me, and this one would prove to be especially memorable. Rupert, as he always did, moved past any pleasantries to get to his point. “John,” he said, starting out carefully, “I guess you heard the news. I’ve got offers from three bidders to buy 21st Century Fox and Sky. What do you think?”