Copyright The Boston Globe

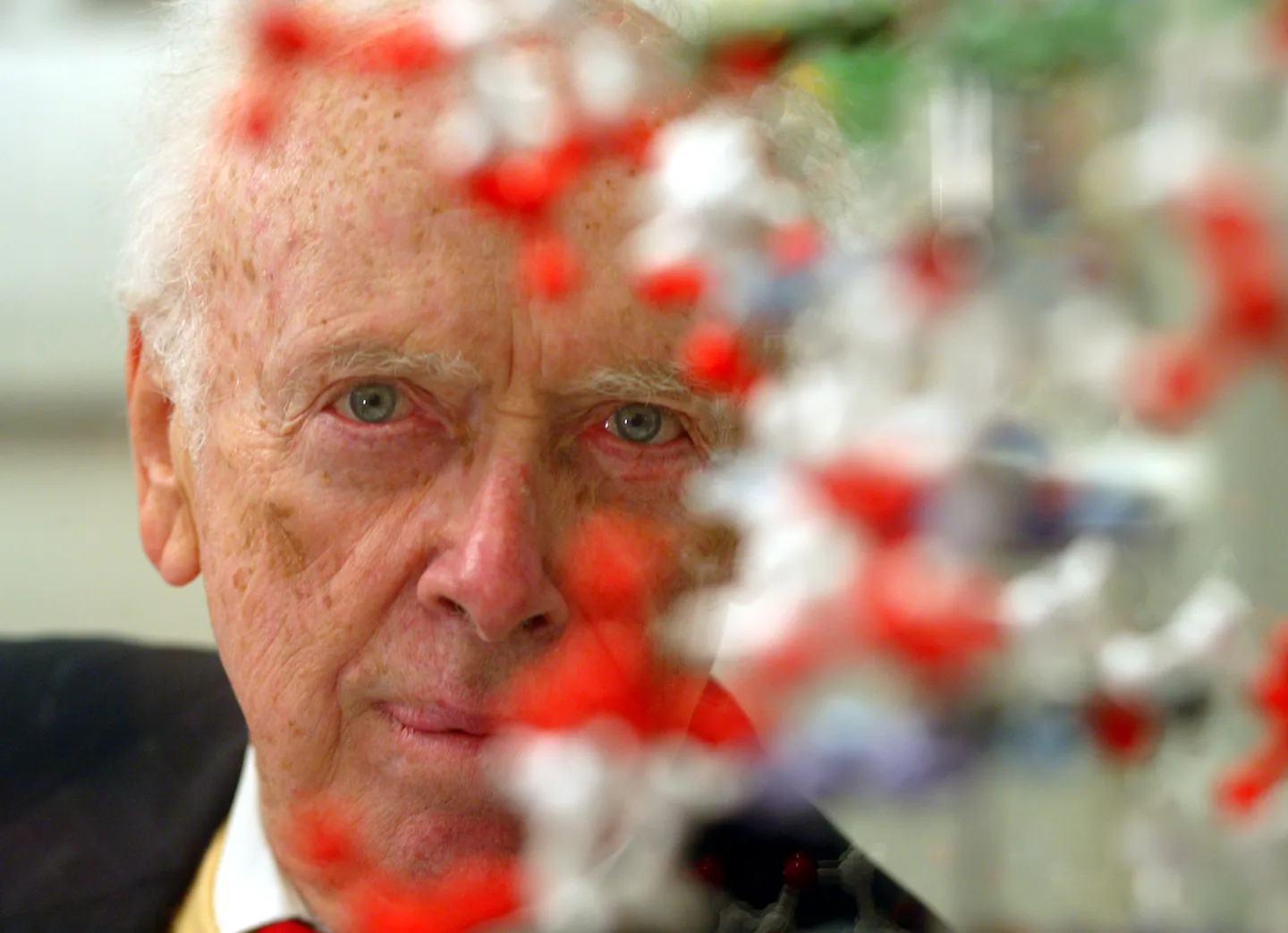

His son Duncan told The New York Times that Dr. Watson, who was 97, died in an East Northport, N.Y., hospice on Long Island after having been treated in a hospital for an infection. Dr. Watson was one of three recipients of the 1962 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for discovering that the structure of DNA was a double helix. The others were Francis Crick, his collaborator, and Maurice Wilkins. In making their discovery, Dr. Watson and Crick drew upon the research of Wilkins and his colleague, Rosalind Franklin, who died in 1958. The prize is not given posthumously. Dr. Watson’s “The Double Helix” (1968), a warts-and-all account of the discovery, became a surprise bestseller and was later made into a film. Widely regarded as a classic firsthand description of how science is done, the book helped seal Dr. Watson’s status as a near-legendary figure. Part of the legend sprang from the sheer magnitude of what he’d helped do in finding the double helix, which is generally considered the most important discovery in 20th-century biology. In the words of Nancy Hopkins, an emerita professor of biology at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and former student of Dr. Watson’s, “How many discoveries in science really change people’s thinking — perhaps the health of a whole species?” Part of Dr. Watson’s special status was owing to the striking figure he cut: brash, boyish, irrepressible — and controversial. “I found him the most unpleasant person I had ever met,” his onetime Harvard colleague E.O. Wilson wrote. Wilson, a notably amiable man who later reconciled with Dr. Watson, dubbed him “the Caligula of biology.” In 2007, a series of comments from Dr. Watson about women in science, antisemitism, and racial disparities in intelligence drew widespread condemnation. Dr. Watson wrote in a memoir, “Avoid Boring People,” that “Anyone sincerely interested in understanding the imbalance in the representation of men and women in science must reasonably be prepared at least to consider the extent to which nature may figure, even with the clear evidence that nurture is strongly implicated.” In an interview with Esquire magazine, Dr. Watson asked, “Should you be allowed to make an antisemitic remark? Yes, because some antisemitism is justified.” He also said that Ashkenazi Jews had a naturally higher intelligence than other people. Dr. Watson created another furor when he speculated in a Times of London interview about the genetic inferiority of Africans and those of African descent. “All our social policies are based on the fact that their intelligences is the same as ours — whereas all the testing says not really.” Responding to a hail of criticism, Dr. Watson issued a public apology. “I cannot understand how I could have said what I am quoted as having said,” the apology stated. “There is no scientific basis for such a belief.” A week later, Dr. Watson abruptly retired as chancellor of Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, in New York, and stepped down from its board. He had served as the laboratory’s director from 1968 to 1993. In a 2019 PBS “American Masters” documentary, “Decoding Watson,” he contradicted that apology. “I would like for [his views] to have changed, that there be new knowledge that says that your nurture is much more important than nature. But I haven’t seen any knowledge. And there’s a difference on the average between Blacks and whites on I.Q. tests. I would say the difference is, it’s genetic.” Shortly after the broadcast, Cold Spring severed all relations with Dr. Watson, condemning his remarks as “unsubstantiated and reckless.” Despite Dr. Watson’s penchant for going his own way — or perhaps because of it — he proved a gifted administrator. “I always thought it’s better to run an institution [yourself] than to let someone else do it,” he said in a 2002 Boston Globe interview. “You spend less time running something than being mad about someone else’s mix-ups.” Dr. Watson is widely credited with rescuing Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, a premier research institute in the biological sciences, from financial difficulties and significantly improving an already-stellar reputation. “It’s never fun being in trouble,” Dr. Watson said in that Globe interview. “I would never say anything [just] to be unpleasant; it was always to get something done. So being a boat rocker, sometimes you’re thrown out of the boat. That’s the price you may pay.” The degree to which Dr. Watson remained a figure of controversy was evident in 2018 when Eric Lander, founding director of the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, was widely criticized for offering a laudatory toast at a 90th birthday celebration for Dr. Watson at Cold Spring Harbor. Dr. Watson’s fellow Nobelist Francois Jacob described the young James Watson this way: “Tall, gawky, scraggly, he had an inimitable style. Inimitable in his dress: shirttails flying, knees in the air, socks down around his ankles. Inimitable in his bewildered manner, mannerisms. . . . A surprising mixture of awkwardness and shrewdness.” Dr. Watson was also inimitable in his candor. “The Double Helix” begins with the sentence, “I have never seen Francis Crick in a modest mood,” and takes off from there. In fact, Crick, who died in 2004, was and remained a good friend. A man of strong opinions, Dr. Watson never hesitated to share them. Even as a grand old man of science, Dr. Watson very much remained the enfant terrible. The official reason for his resignation as head of the National Institutes of Health’s Human Genome Project in 1992 was possible conflicts of interest in his financial holdings. It was generally assumed that the actual reason was his inability to get along with NIH director Bernadine Healy. As for Dr. Watson’s 2002 memoir, “Genes, Girls, and Gamow,” it devoted far more space to his single-minded pursuit of the opposite sex than to any scientific endeavors. The surehandedness of his stewardship over the Human Genome Project helped ensure eventual completion, ahead of schedule and under budget, of the decoding of the 3.2 billion chemical letters, known as base pairs, within human genes. Perhaps most notable of all, though hardest to put a value on, was Dr. Watson’s service as de facto director of the field of molecular biology during its early years. “In ’53, the number of people really interested in DNA in the world probably was less than 50,” he said in that Globe interview. Within two decades, it had come to be regarded as perhaps the preeminent scientific discipline of its time. “It was one of the absolutely great eras in science, from 1950 to, say, 1970,” he said. No one did more to bring that about than Dr. Watson. He spent 21 years teaching at Harvard, ultimately receiving the highest honor the school can bestow on a faculty member, a university professorship. He used Harvard as a bully pulpit to promote molecular biology (the cause of much of the friction with Wilson and more traditional biologists). At Cold Spring Harbor, he had, if anything, an even bullier pulpit, being proprietor as well as preacher. Just as “The Double Helix” had enormous success as a work of popularization, his textbook “Molecular Biology of the Cell” (1965, with subsequent revised editions) had comparable success as a codification of the discipline. Another textbook, “Recombinant DNA” (1983), has also gone through several editions. James Dewey Watson Jr. was born in Chicago on April 6, 1928, the son of a debt collector and Jean (Mitchell) Watson, a University of Chicago admissions officer. A child prodigy, he could read 500 words a minute, appeared as a contestant on the radio show “Quiz Kids,” and entered the University of Chicago at 15. An interest in bird watching led Dr. Watson to major in zoology. He graduated in 1947. Turned down by both the California Institute of Technology and Harvard, he undertook graduate studies at Indiana University, where he turned to microbiology. After getting his PhD, in 1950, he won a fellowship to study in Europe. He became increasingly intrigued by what he would later call “the most golden of molecules,” DNA. Dr. Watson decided the best place to do DNA research was Cambridge University. There he met Crick, 12 years his senior, who was finishing up a doctorate in biology. Different in age, experience, and nationality, they were as one in attitude. As Crick later put it, “a certain youthful arrogance, a ruthlessness, and an impatience with sloppy thinking came naturally to both of us.” It took them roughly two years of trial and error. At one point, Crick was ordered not to do work on DNA by his laboratory head. At another, Dr. Watson nearly lost his fellowship, since he had received it to study biochemistry in Copenhagen. Furthermore, they were deeply fearful of losing the DNA race to Wilkins or Franklin, in London, or the American chemist Linus Pauling, at Caltech. But in the end they prevailed, completing their model of the molecule on March 7, 1953. As Dr. Watson famously wrote at the end of “The Double Helix,” “I was twenty-five and too old to be unusual.” Among the many awards Dr. Watson received were the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor, in 1977, and the National Medal of Science, in 1997. Publication of Dr. Watson’s 2003 book, “DNA: The Secret of Life” (written with Andrew Berry) was the basis of a five-hour PBS documentary series that year. Dr. Watson made headlines in 2007 when it was announced he was one of the first two people to get a map of his personal genome — the other was the scientist and entrepreneur J. Craig Venter — giving a detailed description of his individual DNA. “I knew I was risking possible anxiety when I saw it,” he told reporters. “But it’s much more that if I don’t sleep at night it’s due to thinking about Iraq rather than about my genome.” Dr. Watson’s one stipulation was that he not be told if he had a genetic predisposition for Alzheimer’s disease. Looking back on nearly half a century at the forefront of science, Dr. Watson tried to explain in that 2002 interview his working method. “Some people accept things too slowly. Why not assume it’s right and play out its consequences? So I like to be about four steps ahead of everyone. Most people are afraid of being one step ahead. They’re afraid of being proven wrong. Well, I say a bad idea is better than no idea. So I’ll believe in a bad idea until there’s a good idea.” In 1968, Dr. Watson married Elizabeth Lewis, an architectural preservationist who was then a Radcliffe College junior. They had two sons, Duncan and Rufus. The Times reported that Dr. Watson leaves his wife, sons, and a grandson. Funeral arrangements were not immediately available.