Copyright phillyvoice

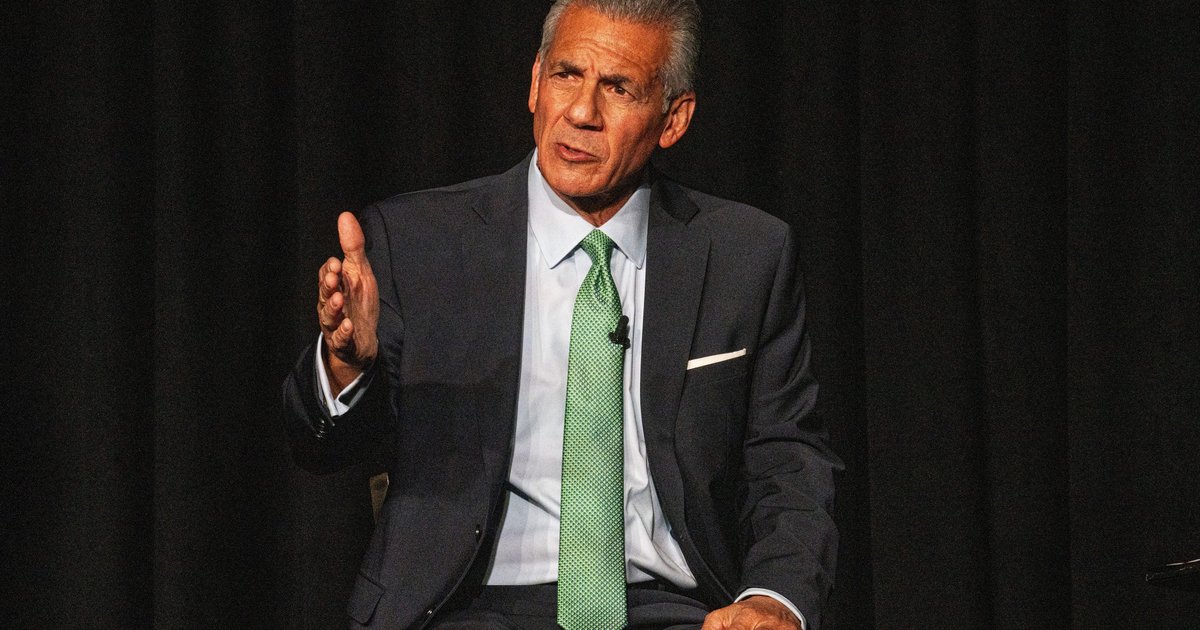

Jack Ciattarelli, a Republican former assemblyman hoping to be elected governor on Nov. 4, wants to pull New Jersey out of a multistate compact that boosts costs for fossil fuel plants in hopes the withdrawal will control recent rises in electricity rates. Ciattarelli, who has made rising utility bills a focus of his campaign for the governorship, says it's time for New Jersey to leave the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative again, arguing a program created in 2005 to limit emissions is now just boosting costs for Garden State ratepayers. SIGN UP HERE to get PhillyVoice's free newsletters delivered to your inbox "That carbon tax initiative has been a failure. Air's no cleaner. Electricity's only more expensive," Ciattarelli said at last month's debate with Democratic candidate Mikie Sherrill. "By pulling out of RGGI, we can save half a billion dollars a year for ratepayers." The Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative – or RGGI, pronounced Reggie – is a cap-and-trade system meant to lower greenhouse gas emissions by requiring fossil fuel plants to purchase tradable emission allowances at annual auctions. In effect, member states require fossil fuel plants within their borders to pay to pollute. The cost of purchasing those allowances is added to the cost of producing electricity, raising rates for fossil generators in RGGI states, which receive revenue from the sale of emission allowances. The added costs have impacts at multiple levels. By raising operating costs for fossil generators, the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative can direct grid demand to generators in other states that would be more expensive than those in New Jersey if not for the added cost of emission allowances, said Richard Tabors, president of energy consulting firm Tabors Caramanis Rudkevich. In some cases, the dynamic results in increased emissions because the allowances can push costs for gas plants in RGGI states past those of coal plants in states not party to the initiative, leading the grid to use generators that create more pollution. PJM Interconnection, which operates the grid used by New Jersey and 12 other states, selects power producers beginning with the lowest price and moving upward until it has drawn enough electricity to meet demand. That means some New Jersey plants run less often than competitors in non-RGGI states because of the cost of emission allowances. "The way the math works out is that New Jersey, because it had the penalties on its high-quality (gas) units and gas prices went up again a little bit – a lot for a while – it meant that coal-fired generation in a state that did not have RGGI rules was supplying energy to the clean state of New Jersey," said Tabors. New Jersey has left RGGI before. Under Republican Gov. Chris Christie, the state pulled out of the initiative in 2011, then rejoined under the current governor, Phil Murphy. Murphy, a Democrat, leaves office in January. RGGI was initially successful in reducing emissions by pushing power production away from the plants that produce the most pollution. Mostly, those were coal plants, and the last coal-fired generators in New Jersey closed in 2022. Between 2009 and 2023, Delaware, Maryland, and New Jersey collectively reduced their carbon dioxide emissions by 46%, Tabors found in a February white paper. But that dynamic reversed as New Jersey moved its generation toward natural gas and renewables. Because of the emission allowances and increases to the price of natural gas, among other factors, coal plants in Pennsylvania and other PJM states ran more often. Tabor's study estimates that in 2025, carbon dioxide emissions would rise by 2.9 million tons and electricity spending would increase by a net $436 million across the three RGGI states because of costs added by the initiative. "The penalty was very much focused on coal-fired generation, and it was successful," Tabors said. "Now, you have to ask the question: Is RGGI still doing what it was designed to do? For New Jersey, the answer is pretty clearly no." Because RGGI effectively levies a surcharge on some generators that is passed through to ratepayers, withdrawing from the program would necessarily reduce electricity costs, though the degree of savings is less clear. There's no guarantee that fossil generators that must buy emission allowances under RGGI would remove the full cost of those allowances from their prices if New Jersey withdraws from the program. Nothing apart from market forces would demand they do, and shifts in the price of natural gas and coal can already make RGGI gas plants cheaper than non-RGGI coal plants. "It would definitely reduce the prices in the energy market, but I need to follow the ball a little further to see what happens after those prices go down," said Brian Lipman, director of the state rate counsel division, which advocates for ratepayers on utility matters. Most of the money generated by the sale of RGGI emission allowances is returned to participating states, though a small percentage is withheld to fund the organization that auctions off allowances. The revenue can be significant. It brought New Jersey as much as $275 million in 2024, according to a New Jersey Monitor review of auction results. Overwhelmingly, New Jersey has used that money to fund electric vehicle infrastructure and subsidize purchases of medium- and heavy-duty electric vehicles, like buses, though significant portions have also gone to shore restoration, building electrification, and carbon sequestration. The Board of Public Utilities could fund those programs through the state's societal benefits charge, a separate surcharge applied to New Jersey utility bills, Lipman said. More recently, revenue from the societal benefits charge and RGGI was tapped to directly reduce ratepayer bills through bill credits that will be applied to balances accrued in September and October. Murphy and other Democratic state leaders announced that plan earlier this year in response to anger about rising utility bills. Ciattarelli's campaign said the state could still fund those priorities absent RGGI revenue. "The budget has gone up 70% in 8 years," said Nick Poche, a campaign spokesperson. "The idea that we can't prioritize how to better spend our money and make sure key priorities are taken care of is a false premise." Other states' participation in RGGI could also change the impact of a withdrawal. At present, New Jersey, Maryland, and Virginia are the only three PJM states to participate in the initiative. Ten states, all of them in the northeast and most run by Democrats, are enrolled in RGGI. Pennsylvania sought to join the compact in 2022, but that bid has been marred by litigation that questions whether state regulators encroached on lawmakers' constitutional taxing authority. Electricity on PJM's grid is sold along the entire 13-state market, and the financial benefits of New Jersey withdrawing from RGGI would be spread along that grid. In the same vein, more states joining RGGI would limit its impact on the competitiveness of New Jersey plants, though there's little indication elected leaders elsewhere would join the program as rates rise along the entirety of PJM's grid. "If Pennsylvania was in RGGI, they would have the same surcharge, and they would not be cheaper than the New Jersey plants," said Lipman, whose office has not taken a formal position on RGGI. The New Jersey Legislature's composition – Democrats hold majorities in the Assembly and Senate – may stall efforts to withdraw from the compact. Republicans hope to gain control of the Assembly after November's elections, but Senate seats are not on the ballot. State law requires the Department of Environmental Protection create a greenhouse gas emissions trading program to participate in RGGI. If he wins, Ciattarelli is likely to have a majority of the Board of Public Utilities. At present, three of the five Board of Public Utility seats are filled, including a seat held by Republican Commissioner Michael Bange. Confirmations could give a Ciattarelli governorship a majority on the regulator's board. It's not clear how the board's current members would respond to a gubernatorial push to withdraw from RGGI, nor is it clear whether the Democrat-held Senate would confirm Board of Public Utility nominees who would vote to depart from the compact. The board's commissioners serve six-year staggered terms. Bange's term expires in 2030, while BPU President Christine Guhl-Sadovy's term expires in 2029. Commissioner Zenon Christodoulou is set to remain until 2028. New Jersey Monitor is part of States Newsroom, a nonprofit news network supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. New Jersey Monitor maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Terrence T. McDonald for questions: info@newjerseymonitor.com.