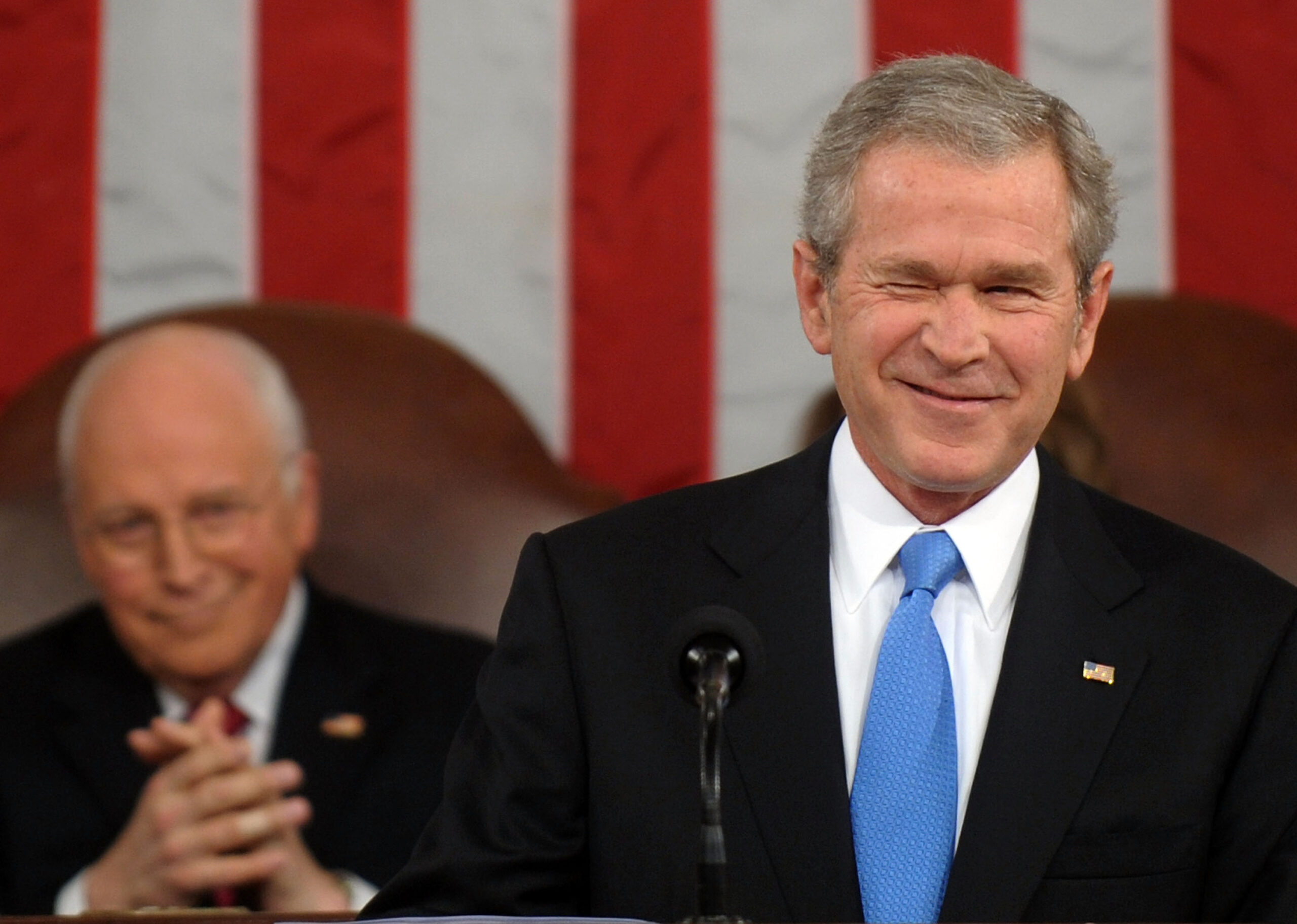

“That’s not the way the world really works anymore,” he continued. “We’re an empire now, and when we act, we create our own reality. And while you’re studying that reality—judiciously, as you will—we’ll act again, creating other new realities, which you can study too, and that’s how things will sort out. We’re history’s actors… and you, all of you, will be left to just study what we do.”

I don’t like being a wet blanket; it fits poorly with my style. Human affairs are stupid and ridiculous as a rule, sure, but I prefer to take the cash and let the credit go.

But things are all looking pretty grim, aren’t they? The world is not appreciably more peaceful than it was on January 20; the United States is not appreciably more prosperous. The Trump administration has only limited responsibility for this. The grandiose peace agenda always depended on third parties that are at war not because they’re bored but because they feel there are matters of national interest at stake; the appalling state of the fisc and the ongoing economic dysfunctions are a legacy of the Covid era. Donald Trump came to office the second time holding a rather bad hand of cards, and any administration would have struggled to play a winning match. The politics have been constraining in certain respects, too; most conspicuously, the One, Big, Beautiful Bill was always doomed to be a dog’s breakfast, and, although not a very good piece of legislation per se, it is probably the best or near the best that it could have been while remaining viable.

This is not, however, to say that the first nine months of play couldn’t have been a bit sharper—quite a bit sharper, in fact. The DOGE caper reduced headcount and some amount of pocket-change discretionary spending, but it failed to produce the sort of deregulation program that was needed to offset the anticipated economic costs of a more aggressive protectionist agenda. That agenda’s rollout was a clumsy bit of work, with a head-scratcher tariff schedule apparently generated by an AI bot—much of it immediately walked back—and an aspirational at best commitment to industrial investment. The result, rather than a manufacturing revival and rebalancing of trade, has mostly been confusion and capital hedging. The newly announced changes to H1-B immigrant visa issuance have baffled policy experts, both immigration restrictionists and wonks actually allied with the H1-B-hungry tech lobby; it appears to be a top-of-the-head idea to shake down tech companies, which, while perhaps a sympathetic goal, is one that can probably be achieved in more thoughtful, constructive ways. In the great pinball machine of foreign policy, the U.S. has caromed wildly between the bumpers of deal-making and hawkish threat-mongering. Much, indeed most, of the administration’s policy seems improvised rather than planned.

Improvisation can be a fine thing, and nobody can complain about taking quick wins where available, but some problems do actually require elbow grease and strategies hatched for a timescale longer than a week’s news cycle. This has been a recurring theme in the Trump administrations, almost a syndrome. The problems of today look a lot like the problems of yesterday, and yesteryear. The administration is simply not very good at sticking with things that are difficult. In 2016, Trump said he was going to end the constant foreign adventurism, end the free rides for so-called allies. At the beginning of his first term, the United States had troops in Syria and Afghanistan; at the end of his first term, the U.S. still had troops in Syria and Afghanistan. He gave up because the generals pushed back too hard, and making them do anything in particular would have required work and an attention span. Ending the Afghan war was left to his successor, Joe Biden. It was another Biden-era development, the outbreak of the Russia–Ukraine war, that got more than a third of NATO nations to hit the 2 percent of GDP military spending guideline. (We will lay aside whether all the countries hitting their targets are actually spending the money in a way that increases the readiness of their own nations and the bloc as a whole.) The defense-industrial base is now in actually shabbier condition than it was in 2015. Things that required dedicated, long-term attention went basically undone.

The problems facing Trump 47 appear to be getting the same treatment. Reduction of our involvement in the Middle East is logistically difficult and opposed by a variety of entrenched interests; the White House appears to have decided just to go with the flow. Economic reform is logistically difficult and opposed by a variety of entrenched interests; the White House has articulated a bunch of shoddy policies and largely thrown up its hands about implementing them. (And, in the process, missed some quick wins—why did it take until August to deal with the de minimis tariff exception?) This is certainly better than a Harris administration would have been, but it’s not exactly the legacy-building stuff of a Republican FDR.

This would be less irksome if the administration were not so intent on presenting itself as a mandate-bearing silverback swinging from win to win through the jungle of American political life. It keeps doing things that its own supporters don’t like and telling them it’s good, actually; it continues to act in its policies as if there is no tomorrow in which a hostile party will rule, and as if there are no consequences for feckless action. For a persistently unpopular administration that won the election by an objectively slim margin, this seems unwise.

The last time a Republican administration acted as if there were no limits of physical or political reality, it ended in tears. It’s not too late for the Trump team to learn a lesson and rejoin the reality-based community.