Copyright Variety

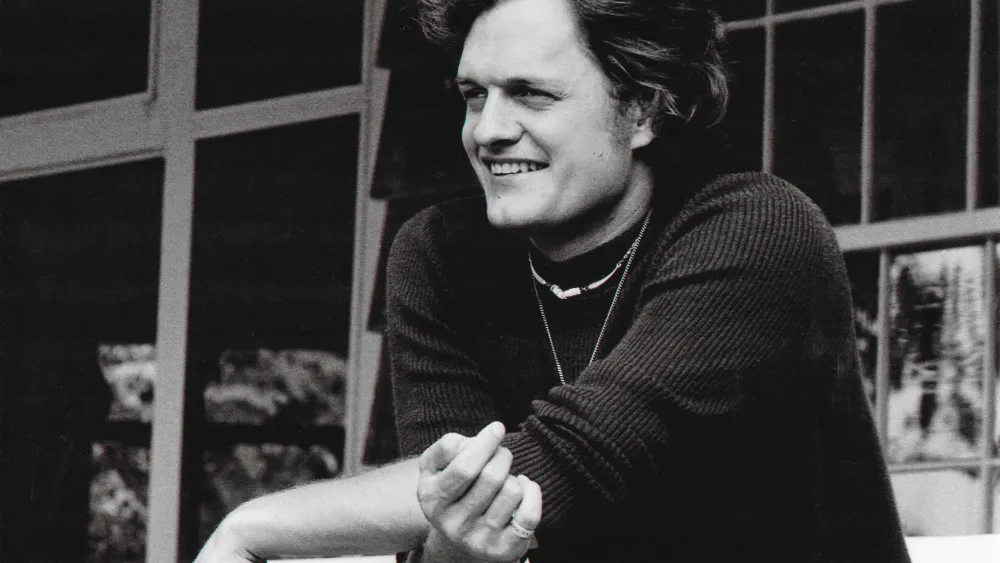

A music documentary built entirely around one song sounds like a precious affair, but it can be a tantalizing one if the song is right. The one-song doc has now emerged as a genre, and in a small way it’s an exciting one. I dug “The Greatest Night in Pop” (2024), about the creation of “We Are the World” (though that was obviously an anomaly of a song), and also “Hallelujah: Leonard Cohen, a Journey, a Song” (2021), which explored how a tune that wasn’t even all that wonderful in the original recorded version could evolve, over time, into a transcendent global hymn. The latest one-song music doc, Rick Korn’s “Harry Chapin — Cat’s in the Cradle: The Song That Changed Our Lives,” feels like it was influenced by the Cohen film. It, too, captures a song that became a hymn, one that grew larger than the artist who recorded it ever imagined, becoming part of the story of its time. Yet the film’s title throws down a bit of a gauntlet. Was Harry Chapin’s “Cat’s in the Cradle” really the song that changed our lives? Having seen the movie, my short answer is yes. I mean, it’s not the only song that did that. Looking back, though, I think it changed mine, and I think it changed a lot of people’s. But not because we thought of it that way. It changed our lives because its message, for a pop song, was so original, so tender yet searing, so defining of the experience of both parents and children that you drank in the song’s plainspoken beauty, you thought about the story it was telling, and it had this weirdly large effect. Even if you first heard it as a teenager, as I did, it made you say two things to yourself: that I’m going to be a better parent than that; and that maybe I won’t. That’s the song’s enticing double meaning. In 1974, Harry Chapin was an internationally known folk-rock singer with a nimbus of wavy thick hair and a cleft chin and a handsome geek grin and the voice of a romantic minstrel. He looked more like a ’70s movie actor, or the lost bohemian Kennedy brother, than a pop star (and, in fact, Chapin had worked in movies, getting nominated for an Oscar for “Legendary Champions,” a 1968 documentary about boxing that he directed). Chapin sang story-songs, drawn from his experience, that he presented as parables — like his first hit, “Taxi,” about driving a cab and picking up an old flame from his youth as a fare, and in six minutes that encounter becomes a journey through his life that’s worthy of James Joyce, or at least a great acid trip. Chapin was earnest to a fault, but his brainy charisma made him a sexy troubadour. He was something old and new at the same time: a folk singer, but one who’d come up through the paradigm shift of the singer-songwriter boom, so his populist music was infused with a very particular sort of 1970s therapeutic confessional spirit. “Cat’s in the Cradle” was the lead single off his fourth album, “Verities & Balderdash,” and it took two months to become number one in the country. It struck a chord. In “The Song That Changed Our Lives,” we hear testimonials from an array of musicians who talk about their experience of it, from Darryl “D.M.C.” McDaniels to Judy Collins to Pat Benatar to Dee Snider, who grew up as the ultimate head-banging delinquent and makes a funny point of saying, “I hated acoustic. I hated anything mellow.” But Harry Chapin spoke to him. “Cat’s in the Cradle” is built around an incredibly subtle and powerful psychological insight: that what we pass on to our children, the good and the bad and everything in between, happens in a karmic way. We don’t control it. Yet maybe we can guide it, even as it’s guiding us. The song tells the story of a father who has a son, who looks up to him and wants to spend time with him (“I’m gonna be like you, dad, you know I’m gonna be like you”). But the father never seems to have the time, and that’s how their relationship goes. A few verses later, the son is grown, and the father asks to see him, only now the son doesn’t have time for him. The key lines in the song would seem to be, “And as I hung up the phone it occurred to me, he’d grown up just like me. My boy was just like me.” You could say the message is: As a parent, you reap what you sow. Yet part of the spellbinding quality of “Cat’s in the Cradle,” apart from what Chapin’s musician brother Steve calls the “Appalachian” modalities of its opening chords (he’s right — the song seems to emerge from some ancient folk wilderness) as well as the lyricism of the melody, is how Chapin’s voice somehow expresses both points-of-view at once. It has an edge of wounded defiance (the son wanting to know why his father wasn’t there for him). At the same time, there’s a sadness threaded through it, a stoic heartbreak that unites these two more than the time they should have spent together. Those of us who grew up with fathers who weren’t there for us tended to feel, at the time, like we were the only ones on the planet who had this problem. But “Cat’s in the Cradle” blasted a message out into the world: “No, children of the ’70s with daddy issues, you are not alone. And part of the club you’re in includes…the daddies themselves.” That was the mind-blower. It will come as a revelation to many who watch “The Song That Changed Our Lives” that the groundbreaking lyrics of “Cat’s in the Cradle” were written by Chapin’s wife, Sandy, who is interviewed in the film (she’s a feisty 91). But, in fact, this was something Chapin talked about effusively at the time, to the point that it almost seemed part of the politics of their relationship. He was a loving husband and, back then, a “new male.” It’s not just that he gave credit; I think it was his way of acknowledging that there was something different about the song’s vantage. I wish the documentary had made more of a point of this — of exploring how and why this particular insight into fathers and sons came from a woman. I also wish the movie had mentioned how the villain of the song, if you really look at it, might be late capitalism. The father isn’t a bad guy; his son isn’t a bad guy. But no one has the time! That’s partly because, increasingly in our society, no one did (or does). But, of course, that’s only part of the meaning, because the real meaning is that as a parent, even as you feel that you don’t “have the time” to be spending enough time with your kids, that is always a lame excuse. As the Beatles taught us, the love you take is equal to the love you make. As Harry and Sandy Chapin taught us, the time you have for your kids is the time you create out of your desire to be with them. Even Harry himself didn’t always have the time. The film kind of buries the lead by saluting his extensive charity work, then sneaking in the point that he was doing 100 benefits a year, in addition to 100 shows of his own, which meant that he was away from Sandy and his five children (two with Sandy; three adopted from her previous marriage) two out of every three nights of the year. It’s sure nice talking to you, dad! Yet the documentary demonstrates that Chapin’s kids adored him (they’re all interviewed in the film). And the fact that Harry Chapin, who died at 38 in a freak car accident that he nearly prophesized, was a less-than-perfect and even absentee father only completes the cycle of the song. The movie includes a number of YouTube reaction videos, with younger people listening to “Cat’s in the Cradle” for the first time, and their tearful responses tell the song’s real story: that when it comes to parents and children, none of us may ever feel we give enough time, and that that feeling is timeless.