In The World’s Worst Bet, David Lynch sets out to explain what went wrong with globalization—an idea that was once the hope of a post-Cold War world for growth, prosperity, and peace, but instead became a vehicle for displacement, division, and polarized politics.

The problem, as Lynch, a veteran economics reporter, makes clear in a trip through more than three decades of recent history, is that so very much went wrong: the China shock, or the sudden explosion of low-cost exports beginning a quarter-century ago that shattered many working-class communities; the relentless drive for corporate efficiency and profits; increasingly vulnerable global supply chains; the increased financialization of the economy; the 2008 financial crisis; the pandemic; and the wars, especially in Eastern Europe and the Middle East. It’s little wonder globalization went astray.

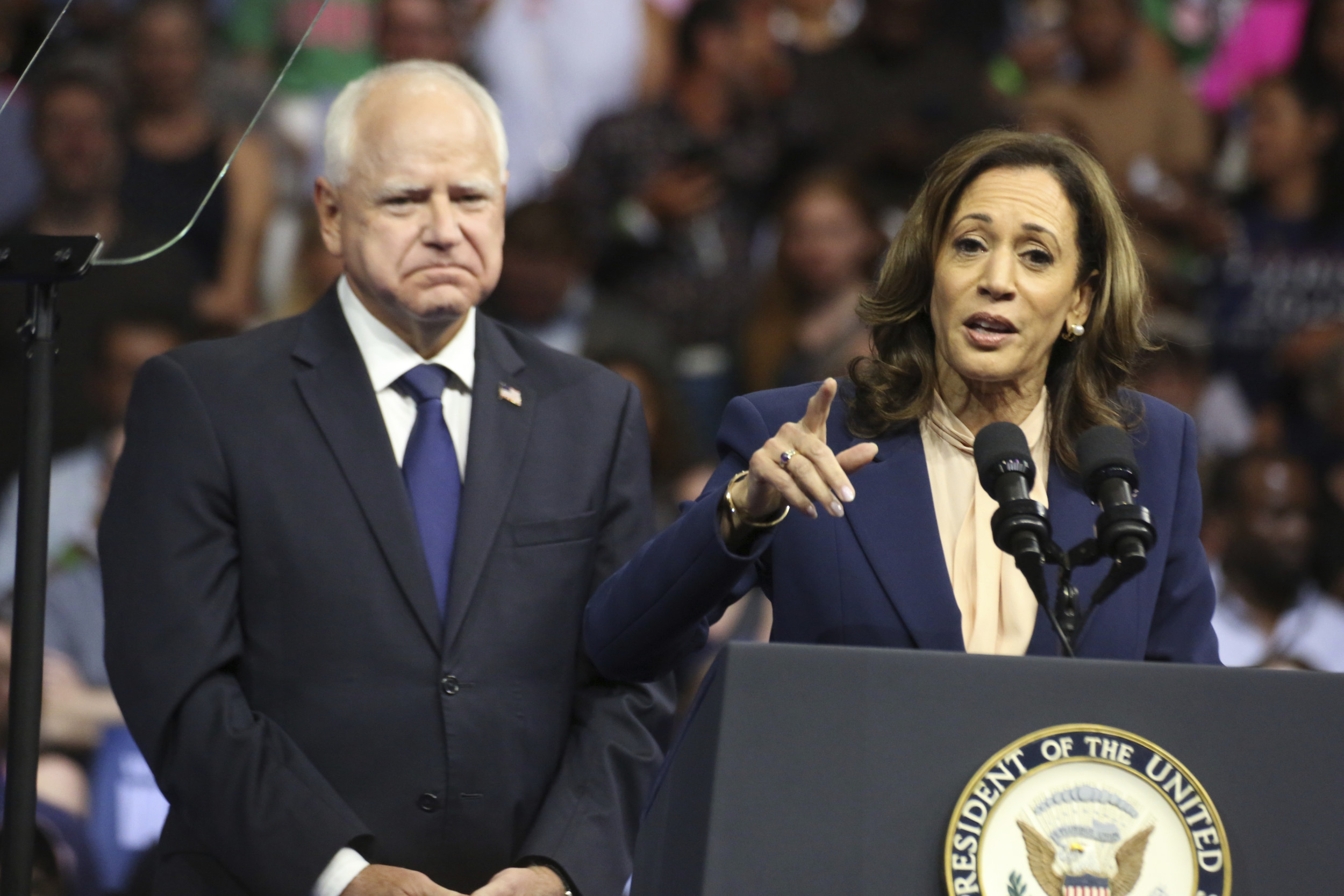

Yesterday’s heresy—fears that globalization would destroy U.S. workers, for instance, or that increased economic integration would turn into a zero-sum game—has become, in most quarters of Washington, today’s conventional wisdom. There is little daylight on economic policy between Donald Trump and Joe Biden, and the only change in Trump’s second term is how much more eager he is to jettison any remnant of the old shibboleths.

The question of how this happened is the heart of Lynch’s book, which offers a compelling, if sprawling, history of an idea that promised a brave new world and seemingly delivered dystopia instead.

The tour through three decades of U.S. economic history, which lately has become political history, is both the book’s vice and its virtue. Lynch’s book features a dizzying array of presidents, policymakers, lawmakers, advocates, workers, investors, and corporate executives to explain exactly how globalization went off the rails.

The vignettes—whether of President Bill Clinton’s efforts to rope China into the global economic system, which culminated in Beijing joining the World Trade Organization at the turn of the century, or of small-town factory workers hammered by disappearing jobs and destroyed communities—make for a wonderful read. But sometimes it is all a bit unwieldy: From the “giant sucking sound” of the 1990s debate over NAFTA to the Seattle protests against the WTO to the rise of Trump to the pandemic’s effect on global supply chains, too much has happened in the last few decades to be packaged in a tidy narrative.

Some of the best bits of the book include a present-at-the creation revisiting of Washington’s embrace of globalization in the 1990s, and especially the conviction that more and freer trade with China, Canada, Mexico, and others would bring both economic and political benefits. That idea, taken as an article of faith at the dawn of hyper-globalization, has come under sustained fire in Washington in recent years. But what is fascinating is to see how many people were already skeptical of this magical realism at the time, and Lynch tells that story well with a cast of deeply drawn characters, such as fair trade activist Lori Wallach and veteran venture capitalist Tim Draper.

The other edifying material is found closer to today, with the rise of Trump; the final conversion of Biden into an avowed skeptic of trade and would-be champion of the working class; and, of course, Trump’s return to the White House with an even bigger wrecking ball to swing against the global trading order. (The George W. Bush and Barack Obama years are about as much fun to read about as they were to live through.)

Lynch is also insightful on what today’s recalibration will ultimately look like. “Looking ahead, neither the unconstrained globalism of the 1989-2008 period nor a retreat into autarky is in the cards,” he writes in The World’s Worst Bet. “Instead, countries and companies will be navigating a far more complex world, choosing industry by industry, one product at a time, whether collaboration or self-reliance is best. Amid the return of geopolitical risk, including that emanating from a less predictable United States, national security considerations will take precedence over economic efficiency.”

All true, and reminiscent of recent diagnoses in books such as Edward Fishman’s Chokepoints and David Sanger’s New Cold Wars. But the national-security imperatives—whether Biden’s “high fence and small yard” to protect U.S. technology or Trump’s efforts to use tariffs and trade cudgels to rebuild critical industries—were not what soured people on globalization to begin with.

Essentially, as with previous experiments in economics, not all the benefits of globalization trickled down: While the U.S. economy as a whole benefited from greater trade, certain zip codes got obliterated as low-cost manufacturing drove entire factories and factory towns out of business. Coupled with the financial crisis and then the supply-chain chaos of the pandemic years, all the smart chatter about globalization’s seamless benefits seemed like so much, as it were, malarkey.

Lynch’s book is very clearly about the U.S. experience with globalization, and its recent reversal by policymakers on both sides of the aisle, despite a few lonely voices still championing greater economic integration and the benefits of trade. In many ways, for many parts of the world, globalization was not a bet gone wrong, but a bet gone spectacularly right. China famously lifted hundreds of millions out of poverty; the standard of living in countries from Bulgaria to Indonesia to Taiwan has soared in recent decades, thanks in no small part to the explosion of trade in goods, services, and financial flows that came after the Cold War.

And for all the post-mortems being written about globalization—entirely understandable given the Trump administration’s ambivalence to trade and bevy of tariffs, and widely shared concerns in the United States and Europe about the damaging impacts of Chinese industrial over-capacity—it’s important to note that globalization is not actually dead yet.

Global trading integration may no longer be soaring as it did in the 1990s and early 2000s, but neither is it in full retreat. According to the World Bank, trade as a share of global gross domestic product remains as high as it was before the pandemic, and as high or higher than it was in the heady years before the financial crisis. More goods and services are being traded than ever before. Some economies, such as the European Union, still embrace globalization, as much as Brussels may vet the odd Chinese investment or fret over floods of discounted goods.

Those different experiences of globalization—ravaged industrial heartlands in the United States and some other developed economies, and better off billions in other parts of the world—hint at what Lynch notes in closing. The backlash against globalization is justified for many reasons, not least the unequal distribution of benefits and the lack of political will or ability to cushion those that lose from it. But it risks going too far.

“As the US tries to course correct from its bad bet on unfettered globalization, it risks overcompensating,” Lynch writes. Consumers worldwide gained immeasurably from the flow of more affordable products and services; economies as a whole, and especially those at the top of the pyramid, gained much more than they lost from globalization.

The one area in which Lynch does not quite deliver, just like an entire generation of policymakers before him, is a nostrum to make globalization really work. He offers prescriptions of the sort that were mooted decades ago but never really panned out, from wholesale reform of the tax code to trade-adjustment assistance for affected workers to a realistic understanding that the factory jobs that vanished will never return in big numbers.

But it is important to figure out why the United States (and many other developed economies, such as the United Kingdom) failed so signally to deliver win-win globalization for all—because what is coming down the pike, he argues, will be much bigger and much more disruptive.

“Even if the United States does hold off a fresh surge of Chinese manufactured goods, there will be other labor market shocks in the future, such as the rise of artificial intelligence and the transition to a low-carbon economy,” Lynch writes. “The US safety net that proved so inadequate amid the tumult of globalization is not ready for what lies ahead.”