Copyright moneyweek

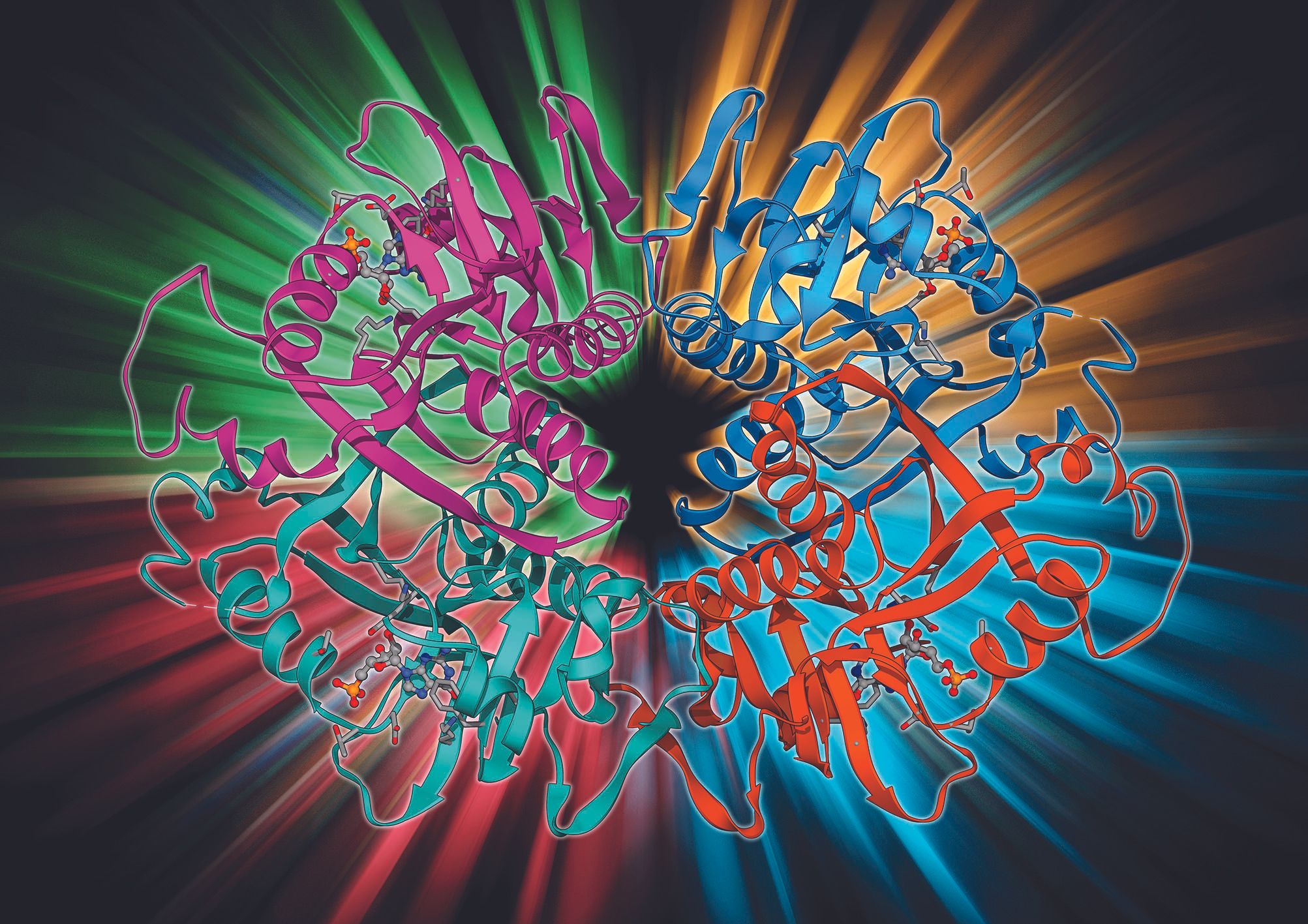

Questions about AI’s stock market dominance are being asked louder than ever. On 27 October, Wired published an article contending that “AI may not simply be ‘a bubble’ or even an enormous bubble. It may be the ultimate bubble.” The article included comments from Brent Goldfarb, co-author of Bubbles and Crashes: The Boom and Bust of Technological Innovation. Goldfarb said that the AI boom ticks every box he looks for in a technology-driven bubble: uncertainty over the ultimate end use, a focus on “pure play” companies, novice investor participation and a reliance on narrative. As Edward Chancellor, financial journalist and former hedge-fund strategist, has pointed out in these pages, the AI bubble is also on shakier ground than many previous technology-driven bubbles, such as the dotcom bubble, the “Roaring Twenties” and the US railroad boom, all of which were followed by major economic depressions. It is also more speculative. Railways, cars and the internet were proven technologies in their bubble periods – the same cannot be said of self-teaching computers. The AI bubble is more “a multi-trillion-dollar experiment” to see if we can arrive at artificial general intelligence (AGI) – technology that successfully matches human levels of intelligence. If that experiment fails, we won’t have canals, railways or fibre-optic cables to show for it, but rather millions of obsolescing computer chips and dormant, debt-funded data centres. AI as a field of research dates back at least to Alan Turing, and includes established fields such as machine learning and computer vision; generative AI is a newer subdivision that has taken shape over the last 15 years. It leapt to public attention – and brought the wider field along with it – with the launch of ChatGPT in November 2022. But it’s worth emphasising that if you are happy to buy Nvidia shares at current prices, you are effectively betting on the long-term profitability of generative (and its newer subset, “agentic”) AI, not the field as a whole. And even the bulls are nervous about the prospects for that. “AI... is driving trillions in spending over the next few years and thus will keep this tech bull market alive for at least another two years,” says Dan Ives, head of global technology research at Wedbush Securities. That is significant as Ives is one of the great tech bulls. If even he is implicitly conceding that the current bull market could end and suggesting a possible timeframe, it shows that doubt is creeping in. The nature of the AI bubble “This time it’s different” is regarded as one of the most dangerous phrases in investing, but it’s a refrain that AI’s proponents turn to increasingly frequently. The companies driving AI today, they say, are highly profitable, unlike the proliferation of profitless internet start-ups in the dotcom era. That holds true of Nvidia as well as the “hyperscalers” (Alphabet, Amazon and Microsoft), but none of these are profitable because of revenue generated by generative AI products. They were already highly profitable (and, for the most part, less capital-intensive) before the arrival of ChatGPT. No one denies there is money to be made selling computer chips or cloud computing. But AI is a different story. Step back and look at generative AI firms in isolation, and the current set-up looks a lot like the dotcom bubble. Venture capital is flooding into speculative businesses that burn through cash with no credible plans to turn that into profit any time soon. James Mackintosh of The Wall Street Journal observes that the dotcom bubble kept inflating between 1995-2000 despite media references to the bubble increasing every year throughout this period. Bubbles can keep growing, even if everyone knows they’re bubbles. A bubble usually bursts after encountering some form of pin. No one knows what that will be for AI, but a contender is an energy-driven inflation crisis. AI requires vast amounts of energy. Policymakers can make life as easy as possible for AI developers, but they can’t control energy prices. The more advanced AI models become and the more users they acquire, the more energy they are likely to consume. And there are signs that AI is already making energy more expensive for US consumers. Bank of America deposit data shows that average electricity and gas payments increased 3.6% year-on-year in the third quarter of this year. Whether or not energy-driven inflation reaches a point where it poses headaches for US politicians, it doesn’t take much imagination to see it quickly becoming a problem for AI developers themselves. OpenAI’s CEO Sam Altman wants his firm to have 250 gigawatts (GW) of data-centre capacity by 2033. According to Bloomberg’s Liam Denning, that’s equivalent to about a third of peak demand on the US grid and more than four times all-time peak electricity demand for the state of California. Nvidia’s CEO Jensen Huang says 1GW of data-centre capacity costs $50 -billion - $60 billion to build (of which $35 billion or so goes on Nvidia’s chips), so building this could cost OpenAI north of $12 /trillion That simply it isn’t going to happen – certainly not in anything like the next eight years, at least – but the numbers show just how much energy AI’s biggest players are planning to consume. Even with energy prices where they are, the economics are stretched thin for AI developers. OpenAI posted an operating loss of $7.8 billion in the first half of 2025, according to tech news site The Information. Annual recurring revenue is set to exceed $20 billion this year, but OpenAI’s own projections say it will not be cash flow positive until 2029, when it projects revenue of $125 billion. If the economics of scaling its capacity at pace ever start looking negative, then OpenAI’s semiconductor-spending binge could slow dramatically. If you want an idea of how overblown the stock market’s reaction is to this binge, look no further than AMD (Nasdaq: AMD). On 6 October, OpenAI announced that it would buy up to 6GW of GPUs from AMD, which AMD executives estimated could net $100 billion in additional revenues once the ripple effects are factored in. Within two days of the announcement, AMD’s market capitalisation had increased by around $115 billion – more than the revenue the deal was expected to raise. That’s before getting into the fact that AMD will be paid for the GPUs not with money, but with its own stock. Where are the benefits of AI? Generative AI does at appear to be improving professional productivity. What data we currently have available from the US shows a trend of reasonably healthy GDP growth alongside subdued job creation, which Joseph Amato, president and chief investment officer at Neuberger, calls “an unusual combination that points to productivity doing more of the heavy lifting”. AI is expected to lift productivity in the US by 1.5% over the next ten years, and between 0.2%-1.3% across the G7. But Amato cautions that these gains are far from evenly distributed and that they pose risks of their own. “Lower-end white-collar roles – performing routine analysis or administrative tasks often filled by recent college graduates – face significant displacement risk,” he says. That has profound policy implications. The AI revolution could eat itself. You can’t put an entire generation of the global middle class out of work without expecting substantial economic consequences; perhaps enough to negate all the potential GDP gains. There is evidence that this is already happening. Ron Hetrick, principal economist at workforce consulting firm Lightcast, observes that average real spending on retail goods compared with total employment has been stagnating ever since the housing bubble that led to the 2008 crash. Covid and the consequent stimuli disrupted this trend, but only temporarily: retail spend per employee is now falling again. Hetrick calls AI “a jobs-destroying, money devouring technology” that threatens to accelerate this decline. As retail spending continues to fall, AI companies’ “large enterprise clients will also see their buyers stagnate”. If the world entered a recession, the core business pillars at Amazon, Google and Meta would take a major hit; advertising and e-commerce revenues are all ultimately reliant on a large crop of middle class consumers happily spending money. None of these companies has an AI division that is remotely profitable in its own right, let alone capable of supporting the wider business. AI could deliver some genuinely world-changing social benefits, improved medical research being an obvious example. Google DeepMind’s AlphaFold is a program that can predict the structure of a protein based on the sequence of amino acids that comprise it, which has profound implications for the research of diseases and development of treatments. But two things need to be remembered: firstly, this isn’t particularly new: DeepMind debuted AlphaFold in 2018, so its potential ought to have been priced in before ChatGPT came along. These kinds of techniques are also not generative AI – researchers at the top biotechs are not asking ChatGPT to come up with new amino acid sequences for them, because that’s not how large language models work. More pertinently for investors, it is not a given that the medical applications will be profitable. How to hedge your bets with AI How can investors hedge their bets given these trends? Judicious selection of energy stocks is one way to play the increasing demand for power that AI companies will drive over the coming years. But this window may already have passed: Vistra (NYSE: VST), for example, has gained 60% in the past 12 months and now trades at 22 times forward earnings – which is a reasonable price for a tech stock, but looks steep based on traditional valuations for utilities. That said, if it does turn out to be energy inflation that eventually bursts the AI bubble, then the suppliers ought to catch the tailwinds in the process. An investment trust with exposure to companies powering and building data centres, such as Pantheon Infrastructure (LSE: PINT), can offer exposure to data-centre energy suppliers. Or you could look for undervalued AI plays. Certain semiconductor stocks, such Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (NYSE: TSM), stand to continue benefitting from AI infrastructure spending for as long as it takes the bubble to burst, without the overblown valuations of the big US names. Given TSMC’s effective monopoly on high-end chip manufacturing, it is well-placed to capitalise on whatever technological innovation might follow in AI’s wake if and when the bubble bursts. Chris Beauchamp, chief market analyst at IG, suggests some traditional defensive plays in order to hedge portfolios, including gold, government bonds, defensive shares in sectors such as consumer staples and healthcare, and multi-asset funds. “Finally, with policy rates still elevated, holding cash-like assets is no longer punitive,” he says. “The key is diversification: no single hedge works in every scenario, but a combination can cushion portfolios if AI euphoria fades.” This article was first published in MoneyWeek's magazine. Enjoy exclusive early access to news, opinion and analysis from our team of financial experts with a MoneyWeek subscription.