Love — or at least sex — was in the air of the small, windowless, biosecure room at the Fort Worth Zoo in Texas. Sixteen rectangular, clear plastic bins lined the room’s back and side walls, tiny stages for unlikely romances.

Each bin contained a plastic green pond plant — the kind you would buy for fish to make Nemo feel at home — about an inch of water, and two endangered Houston toads, a drab-looking critter with a pale belly, dark spots, and raised patches of skin that, in a betrayal of the stereotypes, aren’t warts.

It was a Wednesday afternoon over the spring, and Allison Julien, the zoo’s reproductive science biologist, prepped 16 syringes to inject hormones into the croaking male toads to help, well, get them in the mood. The females, hanging out in their respective bins, had already been injected with their doses since it takes them longer to both lay eggs and acquiesce to the next step.

Soon, each female shuffled around her tub, laying a string of thousands of tiny eggs strung together like black pearls. A male clung to her back, his legs wrapped around her body and his little toes mashed to her belly as — and sorry to get graphic here — he peed on her eggs; for this species, sperm is released in their urine. The fake vegetation helped the egg strands spread out to maximize fertilization. And I like to think…might have even helped a little with the ambiance.

You probably haven’t thought much about amphibian-assisted reproduction lately (or, let’s be honest, ever). But in a lab tucked inside the Fort Worth Zoo, scientists are playing matchmaker for one of the rarest toads in the country — performing ultrasounds, injecting hormones, counting eggs by the tens of thousands, and trying to keep a species alive with spreadsheets and syringes.

The Houston toad, once common across southeast Texas, is now so endangered that its best shot at survival involves assisted reproduction, willing landowners, and some very determined humans who want to help them survive again in the wild.

It’s weird, hopeful, kind of beautiful — and it just might be working.

How the Houston toad got pushed so close to the brink

The Houston toad was first identified in the 1940s near an old airfield base in southeast Houston, where crashed planes from World War I military exercises littered the ground.

After that initial discovery, herpetologists made sporadic observations of hundreds of toads at individual ponds, on coastal plains, and in forests across 13 Texas counties, but their sightings were still relatively few and far between.

“The challenge is [the Houston toad has] always been kind of rare,” said Paul Crump, the state herpetologist for Texas Parks and Wildlife, who has worked for nearly two decades on Houston toad recovery. “And we’ve only got these little glimpses into what it’s doing.”

All the while, Houston toad numbers were declining, and declining fast.

By the mid-century, people in the state had introduced non-native species like fire ants that bit and killed juvenile toads, feral hogs that ate them and reduced wetland water quality, and grasses that made it difficult for toads to navigate. Meanwhile, Texas was expanding fast into Houston toad habitat — turning forests and savannahs into farmland, houses and suburban subdivisions, shopping centers and parking lots.

The toad needed help, and so in 1969, it was included in the Endangered Species Conservation Act, the precursor to the 1973 Endangered Species Act, making the Houston toad one of the first federally protected amphibians in the country.

But the listing may have been too late. In the years since, the Houston toad has likely declined more than 90 percent.

The Houston toad isn’t among the class of iconic megafauna like grizzly bears or wolves. It doesn’t grace national emblems like the golden eagle or put food on our tables like Canada geese. But uncharismatic species like the Houston toad still matter.

“They’re like rivets on an airplane,” said Crump. “All these pieces exist in a system, and there’s probably some redundancy, but you can only lose so many amphibian species, just like you can only lose so many rivets on an airplane, before things fall apart.”

And the planet is losing a lot of rivets.

Amphibians are among the most endangered classes of animals on Earth. More than 40 percent are threatened with extinction, and as many as 220 have already blinked out. That means fewer creatures to eat disease-carrying mosquitoes, and fewer animals to feed other animals. So many amphibians died in recent decades in Costa Rica and Panama, for example, that malaria cases in humans in the mid-2000s spiked.

Protecting a species like the Houston toad also means restoring and maintaining habitat. That helps not only countless other native species like quail and deer but also protects aquifers that supply our drinking water.

And while efforts like assisted reproduction may sound herculean (they often are), Diane Barber, the Fort Worth Zoo’s senior curator of ectotherms (animals that rely on external sources for temperature regulation), said they’re relatively inexpensive in the world of keeping species alive.

How assisted reproduction works

If 130,000 sounds like a lot of embryos for a single day’s work, it is.

At the Fort Worth Zoo, technicians individually counted and marked the latest batch of fertilized Houston toad eggs, adding them to the 3 million embryos they and three other breeding facilities planned to catalog. Eventually, they hope to introduce them into the few ponds where researchers know small numbers of Houston toads still exist in the wild.

If it works, that’s a lot of baby toads that can eventually find their own mates.

The species may be critically endangered, but following Marvin Gaye’s advice was never their issue. They’re good at reproducing, said Barber, if they can just live long enough to find each other — a sometimes impossible hurdle for a critically endangered species.

So in 2007, researchers scooped up portions of three Houston toad egg strands and brought them into captivity, and began the years-long process of figuring out how to breed and raise endangered toads.

A few years later, Barber brought toadlets to the Fort Worth Zoo and turned breeding from a series of tossing toads together, crossing fingers, and hoping for the best, to an exercise in spreadsheets, hormone injections, and tediously kept calendars.

Barber keeps records of the genetic lineage of every toad bred in each of the four project facilities. Each Wednesday after breeding, she sits in her office surrounded by drawings and sketches of Houston toads and Puerto Rican crested toads (another amphibian on the brink) and parses the complex data on her monitors, deciding which individuals are best suited for the next week’s matchmaking session.

She has to interpret the results of ultrasounds performed on females to see if they are ready to release eggs. Then she uses a convoluted algorithm to pair together female and male toads best suited by size (if the male is too small, he can’t hold onto the female, and if he’s too big, he might drown her), and, most importantly, by their distance from one another on the Houston toad family tree. She is not selecting for individual traits so much as preventing toad incest.

“We don’t want to breed nieces, nephews, cousins, siblings, brothers, or sisters,” she said. Maintaining genetic diversity in endangered species work can be a major challenge — especially when populations originate from a small number of wild individuals, and every toad is inevitably a little bit related.

If a male contains important genetics — as in, is not closely related to many of the females — but is too small to mate with them, Julien collects his microscopic sperm and either freezes it in a cryopreservation bank or artificially fertilizes a good match’s eggs.

“If the Houston Zoo, for example, has had an important male die, they will ship us the male’s testes and [Julien] will mash them up and preserve the sperm,” said Barber.

Once this intricate process is complete, Barber and her team load the eggs into plastic bags and place them in buckets along with dozens of juvenile toads not needed for breeding for a long drive south to one of the only places in the wild where Houston toads can currently survive.

It’s going to take a whole lot more than hormones to bring the Houston toad back for good

Today, more than 10 million people live across San Antonio, the Dallas-Fort Worth metro area, and Houston. But just past the billboards, six-lane highways, and sprawling development, biologists believe there’s an existing ecosystem where the Houston toad could soon thrive again.

And that’s because the state of Texas has an intricate plan that is finally beginning to lock into place.

This spring, Barber, with her buckets filled with toad eggs in tow, pulled up to the gated entrance of a large property owned by Scouting America Capitol Area Council, an arm of what was formerly known as the Boy Scouts of America. It’s a sprawling piece of undeveloped Texas, with stretches of oak and loblolly pine forests and peppered with scenic ponds — perfect for ropes courses, hiking, and lessons on living in the wild.

Mike Forstner, a Texas State University biologist who has studied the Houston toad for decades, Jon Yates, the CEO of the Capitol Area Council, and a handful of other biologists from TSU and the Fish and Wildlife Service waited for Barber and her precious cargo. Those strings of tiny pearls suspended in plastic bags would soon join any wild egg masses in one of two small ponds on the Scouts’ property, the Griffith League Scout Ranch.

The pond is the Houston toad’s nursery, where, if the eggs are lucky, they’ll hatch into tadpoles, swim out of the mesh baskets where they’ve been placed, and enter the pond’s ecosystem. Eventually, with even more luck, they’ll emerge as toadlets where they’ll wander into the surrounding woods to eat — and eventually return to the pond to find mates.

That this property and the surrounding areas are the only known ecosystem supporting wild Houston toads is ironic — it very nearly was the final nail in its coffin.

When the Scouts inherited the property from the matriarch of an old Texas family in 1997, they had big plans to clear the pines, oaks, and ponds to build a massive Scouts’ events camp. But then the Scouts discovered Houston toads on the property. And so they decided they could make a more nature-based adventure park for their Scouts while also conserving an endangered species.

“There was a lot of consternation (at first),” said Yates about the decision to keep the land intact for conservation. But eventually the Scouts found a good balance: They cut hiking trails, curated education opportunities, and even built a ropes course. Essentially, Scouting America could “still have Scouts on it but do the right thing for conservation,” Yates said.

But even here — in this figurative walled garden as well as a nearby state park — the last remaining wild Houston toads have struggled. Persistent drought in the area has dried many of the ephemeral ponds where Houston toads live, and then a wildfire incinerated much of the remaining occupied Houston toad habitat, including almost an entire neighboring state park.

By 2016, Houston toads were closer to extinction than they’d ever been. “Houston toads went down to a dozen individuals,” said Forstner as he placed pond water in the bags with strings of eggs to acclimate the embryos to the wild. But now, thanks to the Scouts’ effort and assisted reproduction, the population is estimated to be somewhere shy of 800.

The Scouts’ ranch is a good start, but restoring Houston toads in the wild requires more than one population on one piece of land.

And so Crump and Zach Truelock, a private lands biologist with the Amphibian and Reptile Conservancy, along with officials from the USDA’s Natural Resources Conservation Service and US Fish and Wildlife Service, have made it their mission to find toads more homes, largely through an incentive-based state property tax program and a cost-share program for habitat work that helps landowners create places for the Houston toad to live. If landowners agree to manage their property to the benefit of Houston toads and countless other species, the state of Texas will give them a better deal on their property taxes.

Once the program identifies friendly property owners willing to give the Houston toad a leg up, the focus turns to battling a native plant species called yaupon. A prolific grower, yaupon was once kept in check by regular wildfires but now, in the absence of healthy fires, it grows in impenetrable patches like willows on steroids.

So Crump connects landowners with grants that helps landowners pay for either burning or mechanically cutting down the yaupon.

José Bermúdez, a philosophy professor at Texas A&M University, is one of those landowners. Decades before he bought his property northwest of Houston a handful of years ago, the land had been used as a ranch. But when the former owner stopped grazing cattle, yaupon took over. Yaupon branches wove too tightly together for deer and humans and shaded the ground, preventing light and nutrients from growing anything underneath.

With a grant from the Fish and Wildlife Service, Bermúdez mechanically cut down 50 acres of yaupon and created large swaths of open space. His wife takes bird walks through his property and every week records more species, already noticing a difference in habitat. He’s a long way from welcoming Houston toads to his property — he just started his restoration work — but that’s the ultimate goal.

“The Houston toad is like a lot of these iconic species,” he said. “It’s a way of preserving the land for other things.”

Dozens of landowners like Bermúdez participate in the program. But even with federal grants, cutting, burning, and clearing yaupon takes time and money. Why do it? In part because long-term, managing and conserving the habitat may actually save him money.

Thirty years ago, Texas voters made a consequential decision. The state already evaluated the value of agricultural land differently than a house in a city, understanding that 40,000-, 70,000- or 100,000-acre ranches used for grazing cattle weren’t worth the same as even a city block in, say, downtown Austin. The effect was, essentially, a tax break for anyone raising livestock.

But then deer hunters, environmentalists, and landowners had an idea: What if those same benefits could go to people who produced not cows and sheep, but native wildlife like deer, quail, or songbirds?

Texas voters agreed. Now landowners get the same change in valuation by participating in some meaningful conservation practices like setting out bird boxes or feeders, shooting feral hogs, poisoning fire ant mounds, or cutting and burning overgrowth.

Depending on the property size, it could be a difference of tens of thousands of dollars each year. And ultimately, it means someone like Bermúdez is a lot more likely to help out a beleaguered little species like the Houston toad. This kind of capitalistic mutual benefit may just be one of the best approaches to solving our country’s endangered species conundrums, and in a state like Texas, where more than 93 percent of the land is private, a lot is possible — at least when reasonable landowners are part of the equation.

What’s next for the Houston toad?

Not far from the Scouts’ property, land owners Roxanne and Elvis Hernandez aren’t in it for tax benefits — they’re in it for the toads.

A framed painting of the Houston toad even hangs prominently on the wall of their living room, and they yearn for nothing more than the trill of the Houston toad from one of the ponds on their property, which they finally heard for the first time in early May.

But even with their altruistic motivation, keeping up the work is about to get a lot harder.

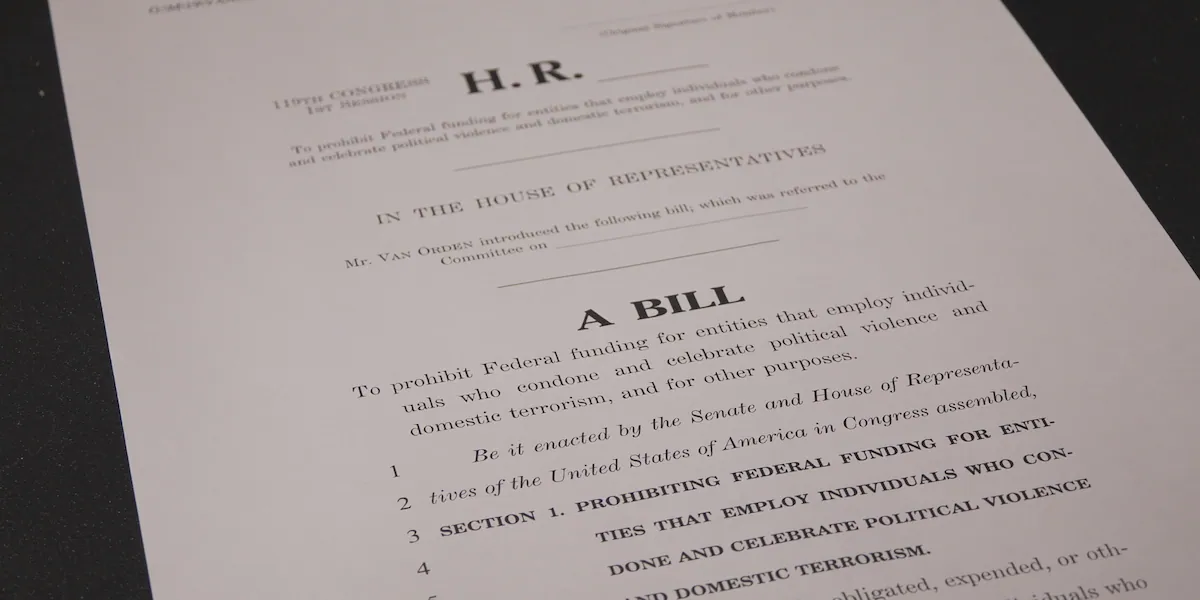

Cuts to the federal government and conservation programs through agencies like the Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) mean that important grants that helped support the work that families like the Hernandezes do may never arrive.

“Habitat work is not inexpensive,” Roxanne Hernandez said. “And any cutback in funding is just a setback for the conservation effort.”

And so I wanted to witness the work still underway. On a muggy spring night after we transplanted all those eggs, I went out with Crump to survey wooded areas where Houston toads once called but hadn’t been heard from in well over a decade. Was it possible they still existed somewhere else in the wild? After all these efforts, had they spread? Had they reproduced somewhere else, tucked away, hidden from all those threats?

We’d been creeping along rural county dirt roads in an old Chevy Silverado. We stopped every so often to hop out and listen again. We heard a lot that night — the cricket frog’s chatter, the Gulf Coast toad’s raspy trill, and the green tree frog’s nasal “quank.” But not a hint of the Houston toad. At nearly 2 am, Crump sighed. But despite our abysmal night, he wasn’t ready to call it.

“It’s either optimism or quitting,” he said about Houston toad recovery efforts. “And I’m not ready to quit yet.”

We drove back to the outskirts of the Scout property. It was 2:30 in the morning when we pulled over on the side of a paved road near rural homes. Crump and Truelock might have felt optimistic, but I sure didn’t. We rolled the windows down and waited, listening as 24-hour highway traffic hummed in the distance.

And then, in the stillness of a Texas night, came the sound: a lone, high-pitched trill, ringing out like a tiny bell. One male Houston toad, calling into the dark, maybe born in a Tupperware of fertilized eggs, maybe wild, maybe the offspring of both — but alive. It wasn’t much. Just one voice. But after everything — the hormones, the spreadsheets, the chainsaws, the habitat deals — it was enough to remind everyone why they keep doing this.

Because if a toad that’s almost gone can still call for a future, the least we can do is try to answer.

This reporting was supported by a grant from the Alicia Patterson Foundation. Vox Media had full discretion over the content of this reporting.