Kanye West making Kim Kardashian cry in a luxury yurt in Uganda. Kanye telling Kris Jenner she makes him feel “demasculated” by urging him back on psychiatric meds. The rapper-producer-streetwear-mogul getting tongue-lashed backstage at Saturday Night Live by Michael Che after an anti-SNL (and seemingly anti-Che) diatribe: “That was fucked up! Why you gonna call me out when I don’t have the chance to say anything for myself?” Ye, as he’s now legally known, shouting down the phone at then-senior presidential adviser Jared Kushner about his fear of being assassinated and his preferred method for entering the White House to meet Donald Trump: “I need to go the exact way a foreign dignitary would go!” And Kanye — in a moment of both foreshadowing and bitter irony — telling Pharrell Williams: “If this was a scene in the fucking Bible, God’s like, ’Okay, I’m not gonna have your wife leave you. I’m not going to have Adidas drop you. I’m not gonna have all your fans turn their back on you.’”

There is a dizzying multitude of vignettes like this in the documentary In Whose Name? (which arrived in theaters September 19), which takes viewers behind the headlines and into something approaching interiority for hip-hop’s most trailblazing — and confounding and frequently infuriating — billionaire multiple-Grammy-winning Nazi sympathizer. Edited from 3,000 hours of footage shot between 2016 and 2024, the film became an all-absorbing life’s work for its director, Nico Ballesteros, who fluked into West’s orbit as a Hypebeast-obsessed, art-school-trained 18-year-old. Against all odds (and despite his relatively scant résumé shooting promos for the Ye-adjacent fashion brand Off-White), Ballesteros became the superstar’s de facto Boswell when another videographer dropped out: hopping international datelines by private jet; sitting in on privileged meetings with the likes of Drake, Anna Wintour, Lady Gaga, Elon Musk, artist James Turrell, LeBron James, and Charlie Kirk; sleeping as little as two hours a night while dedicating around 80 percent of his life over those years to being Ye’s video biographer.

Although the doc is certainly sensational for what it showcases — West and Kardashian renewing their wedding vows in an intimate 2019 ceremony (that notably did not get airtime on Keeping Up With the Kardashians), Ye explaining to a befuddled Ballesteros what it literally means to go “death con 3 on JEWISH PEOPLE,” commiserating with Musk in a strange foam room over baby-mama troubles — on a filmmaking level, In Whose Name? is notable for what’s not there. Namely title cards, talking heads, and only the scantest outside exposition contextualizing what we are seeing.

The result is a cultural artifact that picks up where Netflix’s embattled 2022 Kanye doc Jeen-Yuhs left off but that will likely be more consequential to Kanye stans (if somewhat incomprehensible to anyone who has not closely followed West’s last decade of rants, controversies, corporate bridge-burning, and grand artistic gestures). Upon seeing an early cut of the doc — which is technically “unauthorized,” absent legal approvals from its subject — Ye is widely reported to have remarked: “It was like being dead and looking back on my life.” But true stans of the artist may also wonder at seemingly deliberate omissions. Among them are Ye’s self-professed addiction to porn, his connection to controversial dentist Thomas Connelly (a.k.a. the “Father of Diamond Dentistry” whom Ye is suing for malpractice, alleging Connelly got him addicted to nitrous oxide, leading to “extreme mental and physical distress”), and wife-muse Bianca Censori, whom he wed under strange circumstances and brought to worldwide attention during the span of years chronicled in the doc.

Over an iced café Americano in a quiet bar banquette at West Hollywood’s Chateau Marmont, the lanky Ballesteros, now 28, broke down his multiyear Ye odyssey and how he intends In Whose Name? as a Rorschach test for viewers: open to interpretation rather than a didactic take on the artist.

You got plucked from obscurity to do this project.

Nico Ballesteros: It was a dream, yeah.

He could have easily gone to a far more famous director.

Spike Jonze and Werner Herzog were people that he had in consideration for it. But I don’t think this format could have existed without it being someone who was a kid. It required a level of naïveté and also availableness.

What did Kanye mean to you at that time?

When I started, he was someone who was surely a cultural figure. But I didn’t see him as just a music producer. I saw him as a producer of culture and people. I had an understanding of him being this Central Saint Martins of talent in our society. So when I first started filming it was just for me to observe how he interacted with people — and how people interacted with him. It was an education. It was like winning a golden ticket to Willy Wonka’s factory. Especially because at that time there was so much mystery shrouded around his creative process.

During that conversation with Pharrell, Ye discusses this project as a film about mental health.

But also the idea of being Method actors and we’re all in someone else’s movie. It was very cerebral but also very esoteric. That was the first week I started filming. So I knew the gravity immediately: This is something I got to really buckle up for.

What were the terms of your employment? What were the rules of engagement?

I got a schedule in the very beginning, but eventually the schedule went away. And then it became me texting him directly, like, “Hey, good morning.” Or checking with security or the jet broker to be like, “Hey are we flying out anytime soon?” There were no terms. It was just, “Don’t turn the camera off.” That was the only request I received.

So you’re filming 18 hours a day that entire time?

Oh yeah. My iPhone clips would be like six hours and I’d only stop if there was a restroom break. But truthfully, I never stopped because I was very wary that if I stopped, that’d be the one moment I’d miss something important.

Why did he want a full-time videographer at that time in his life? And do you think the process of being filmed dictated his behavior in certain situations?

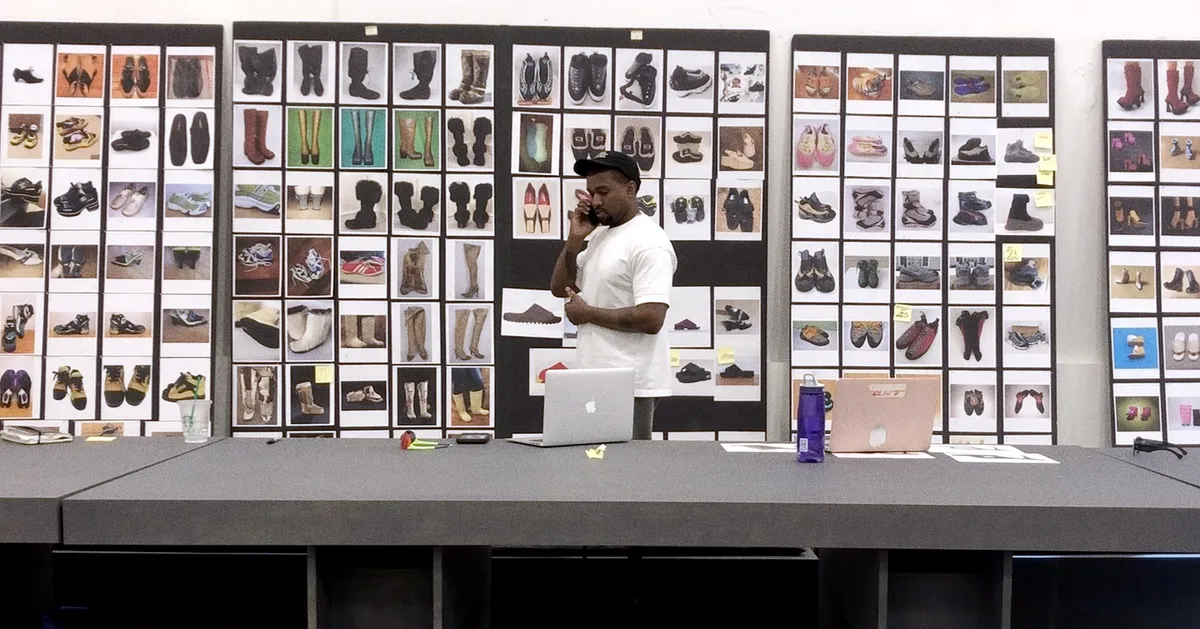

I don’t think he was performing for the camera at all. But I think he was aware of his position. It was when Adidas was providing him with such a level of wealth. The money he was making was unheard of. Liquid cash deposited into his account — more than any ball player, any celebrity — hundreds of millions of dollars. That level of mountaintop being climbed and wanting to provide a window to that: That’s when I really started filming.

To me it seems like a deal with the devil. On one hand, you have access to rarefied realms: seeing the most creative people behind the strictest velvet ropes, capturing the highest-level creative discussions. But on the other hand you have to trade almost everything to do it. All your energy and time.

I didn’t want to do anything else, though. Even as an 8-year-old, I got this little home-movie camera and I would just film my day. Then I’d plug it into the TV at the end and watch it back and relive my day. I just love living life through a camera.

Let’s go through some of the scenes in the doc and you tell me your recollections. In one, Ye is yelling at Jacques Herzog, one of the world’s most acclaimed architects, overriding his ideas on how to design a building and browbeating his creative team.

That was a few days after Uganda. Which was one day after the White House. That’s my favorite scene in the movie. It represents the way Ye went from being a producer to a rapper to a shoe designer and from a shoe designer to a fashion expert. I felt architecture was his next thing. He’s always looking to live this limitless existence. It’s about him trying to understand how to create the future and this externalization of healing. He’s like, “I want to create a space where a child could live for 30 days by themselves without being hurt.”

What was it like to film him visiting Trump in the Oval Office?

I was half-asleep for it. I kept dropping the camera in my lap and I just kept trying to stay awake. It was surreal.

In the Uganda safari scenes, it’s clear Kanye and Kim’s marriage is in deep trouble. It looks like the most miserable family vacation of all time. Externally, meanwhile, the entire world was wondering, What is going on with them? And you’re there filming it.

All I knew was to keep recording and that there would come a time to understand all this through the editing process. It required me to take a step back from culture and society as a whole and just watch everything in totality. People would say to me, “Man, you should journal.” I didn’t have time to journal! But when I watched everything, I was hooked right back into that 19-year-old version of myself. It was like reliving it verbatim.

I have never found Kim to be a particularly sympathetic person. But in your film, I had a lot of sympathy for her. You see her trying to keep her family together while her husband battles mental-health issues.

I always viewed it through a lens of empathy as well as journalistic integrity and objectivity. It goes back to when I was a kid and my parents were going through a divorce; I would just film. Creativity as an escape. So as things were going on with the Wests, even though they were much more elevated than my family, even though we were dealing with celebrities and the world arena, I connected on a human level. Having that camera was something I was familiar with in dealing with difficult situations.

After SNL, where Michael Che seemed like he wanted to punch Kanye, Kanye asks you a direct question: “What did you think?” And you gave an interesting answer: “It’s the start of a transition.” What did you mean by that? And why didn’t you say something more obvious like, “They seem really pissed off at you”?

Celebrities are always surrounded by people telling them what to do, what not to do. And I didn’t speak to him for months when I started filming. Truly, I just observed. I knew I was there to bear witness. So, in that moment, I wanted to be authentic. I didn’t want to give an answer that was superficial. I wanted to make sure it was something to continue the momentum rather than provide a diversion that would change the state of truth.

There’s a remarkable part where Ye comes out during Fashion Week wearing a White Lives Matter T-shirt. You filmed him before and after: first, knowing full well he’s going to troll people, and later, startled that the reaction and outcry was so big. He says something to the effect of “It was a joke and I can’t believe it went so far.” Did you include that as a counterbalance to all the controversy around that shirt?

When I was filming, I never really had time to follow the news too much. I knew that things were obviously being picked up. But I wasn’t even reading headlines. Even when I asked him, “What’s ‘death con 3’?” I truly didn’t understand that was a thing. I didn’t know what it meant in the military context. So, at times, I provided a counterbalance with the media kind of being a character in the film: to show what was the headline versus the body text. But I didn’t explicitly put that in there to counterbalance it. I was just following the story as it happened.

I have to ask a couple of questions about things you chose not to include. Ye married Bianca Censori in 2022. Why is she not in the film?

I just didn’t really have footage of that. Like, that happened after I stopped filming.

A dentist named Thomas Connelly implanted Ye’s titanium dentures and has been accused of getting Ye addicted to laughing gas, which allegedly caused his mood instabilities. Did you ever film footage with Connelly?

No, I stopped filming way before that.

How did you whittle down 3,000 hours of footage to a 106-minute movie? Was it about organizing coherent chunks that tell a story? Or was it, “Okay, here’s Drake.” “Here goes Lady Gaga”?

No, it was always about the story. That kind of mentality, “Oh, here’s Rihanna,” is what I tried and failed to do an earlier cut with. I was following a story about his relationship with America and America’s relationship with him. That’s why it’s dedicated to America — “whatever that is.” The Jack Kerouac quote at the beginning.

How scared were you to show the film to Ye?

I wasn’t scared.

Because he never signed anything that could shut you down?

Yeah, there was no paperwork. I showed it to him three times: at a two-hour-forty-minute mark, a two-hour version and then I showed him the final cut.

What were his remarks each time?

Well, he said, ““It was like being dead and looking back on my life.” And then he would just say how deep it was and how appreciative he is too. He thanked me. He ran into my friend and co-producer Shy Ranje the other day and was like, “I know that was a lot of work and a lot of dedication. Thank you.” I always just felt love and respect from him.

So he never said, “How dare you include XYZ”?

No.

He never wanted you to change anything?

No. In the film, he says, “We’ve got to show all the sides of who we are: the dark and the light.” So I always knew that it had to be something that was well-rounded.