Luca Guadagnino’s After the Hunt is set primarily in the year 2019, a mere 18 months after the Me Too movement took hold of Hollywood and other creative industries, at a potent time for “cancel culture” debates. The film takes place on a college campus — Yale, to be precise — where it depicts students as fiercely political if not naïvely altruistic and faculty as weary referees trying to get home early. And yet, for all its dancing around and within these big issues, the film’s director and cast have refused to let After the Hunt be defined by them. Just about every interview with stars Julia Roberts, Andrew Garfield, and Ayo Edebiri involves some reckoning with the moral state of culture and power (or some ill-conceived tangent). When asked point-blank whether the film was “about” Me Too, Guadagnino told Variety, “It’s a bit of a lazy way to describe it. It’s a passé way of thinking.”

His comments came after the film’s mixed reaction at the Venice Film Festival, which included one journalist arguing that Guadagnino’s latest is anti-feminist. “The idea that something is anti-feminist is a bit generic, and also is so devoid of the pleasure of watching the movie, because look at the fucking movie and enjoy the story of these people,” Guadagnino added in his conversation with Variety. To some extent, he’s right: After the Hunt (which opens the New York Film Festival tonight) is an enjoyable experience. It is sensual and rich in texture with a robust score and expensive-looking costume design. As characters move in and out of lush apartments and dive bars and one especially beloved hole-in-the-wall Indian restaurant, it may take a while to realize that After the Hunt is far more interested in the people talking than in the ideas they’re talking about.

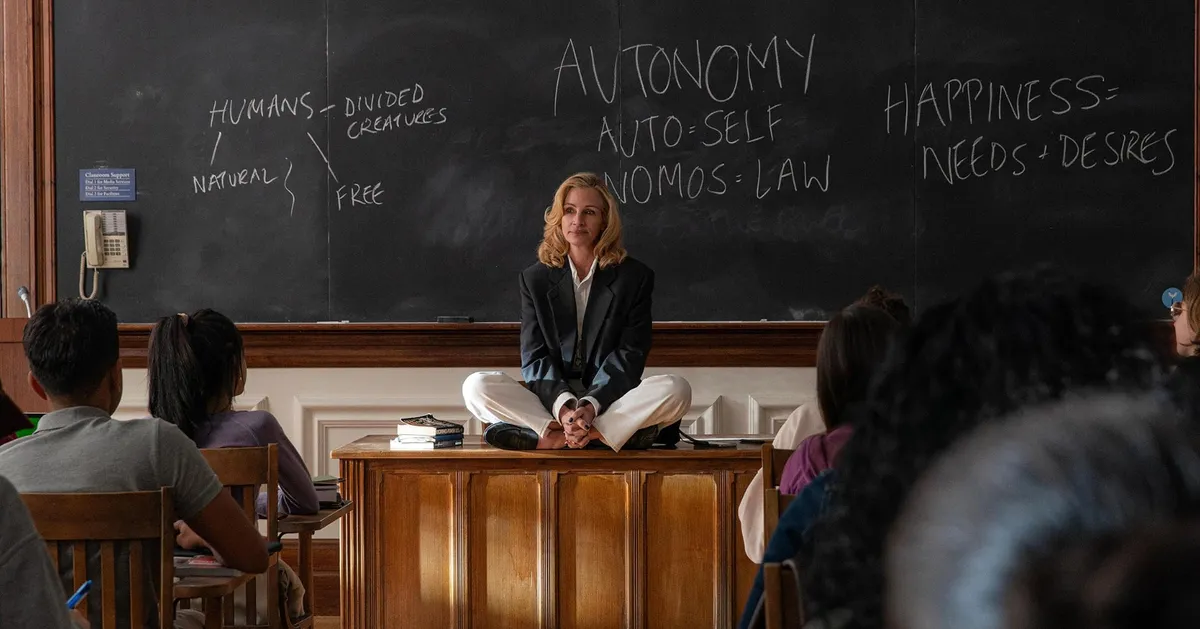

Julia Roberts’s character, Alma, for instance, is not being canceled or being “Me Too’d” — or at least not in such a literal way. Instead, she is unwillingly at the center of a potential sexual-assault case between Hank (Garfield) and Maggie (Edebiri), each of whom has accused the other of something totally serious. After the Hunt is not arguing on behalf of anyone’s innocence, however. The movie finds all of them guilty of something. It’s what they do with their guilt that proves most interesting. Hank descends into hysterics. Maggie grows more withdrawn and unpredictable: She both wants people to know what happened and loathes the attention it brings her. Alma is tormented by her own inability to decide or know with any certainty to whom she owes loyalty or support, in part because she has been through a version of all this before.

As the movie intensifies and complicates the relationships among its central trio, it becomes clear that it’s really about the way these people process pain and rejection. In the back third of the film, After the Hunt turns to Alma’s journey of understanding — of herself, her role on campus, her own beliefs. Alma pushes Maggie to keep the story of her assault to herself; Maggie goes public with Alma’s lack of support. These women, separated by time and social values, are pitted against each other more than they are any of the men in the movie. Both are capable of a kind of violence toward the other, but Guadagnino gives them plenty of agency to continue to escalate their conflict with each other. They are both hurting, and they’re bearing witness to the other’s suffering, but their approaches to healing are fundamentally at odds.

After the Hunt is a character study in the aftermath of pain: how a person is supposed to live with themself and those around them in the wreckage of scandal. It’s neither moralizing nor feminist, in part because these altruisms go out the window in moments of panic and unease. Alma is a difficult character: cold, testy, and guarded. No one sits down with her and feels immediately at ease (except perhaps Chloë Sevigny’s Kim, who happens to be Alma’s therapist). She has toiled in academia long and hard to very little reward, and she has allowed that experience to harden her toward the world around her. She operates as if sympathy is a sign of a weakness, and the stress, in turn, subsumes her, practically eating her alive. “The hardest part for me was not being sympathetic and empathetic. For me as a person, it’s like, ‘Oh, how can I hold her?’ And she was not to be held,” Roberts explained.

That After the Hunt avoids falling into a polemical trap is part of what makes it so fun to watch, no matter how dark or unpleasant the dynamics between the characters become. No one comes out of the film unscathed or as a beacon of anything other than self-preservation. The final five minutes of the film see Alma and Maggie reuniting in the present day. For the first time, it feels like the characters are talking about themselves: their partners; their lives; if they are happy or not happy. They’ve abandoned the notion of ideas and debates, resorting to seeing each other not as totemic concepts but actual people, flaws and all. It’s a relief, almost, to see that Alma and Maggie don’t rekindle the intimacy they once had. In fact, they admit they don’t care for each other at all anymore. Rather than feel bad, as they both have for much of the film, the confession makes them smile. It’s freeing, maybe, to at last be able to tell the truth.