By Pablo O’hana

Copyright metro

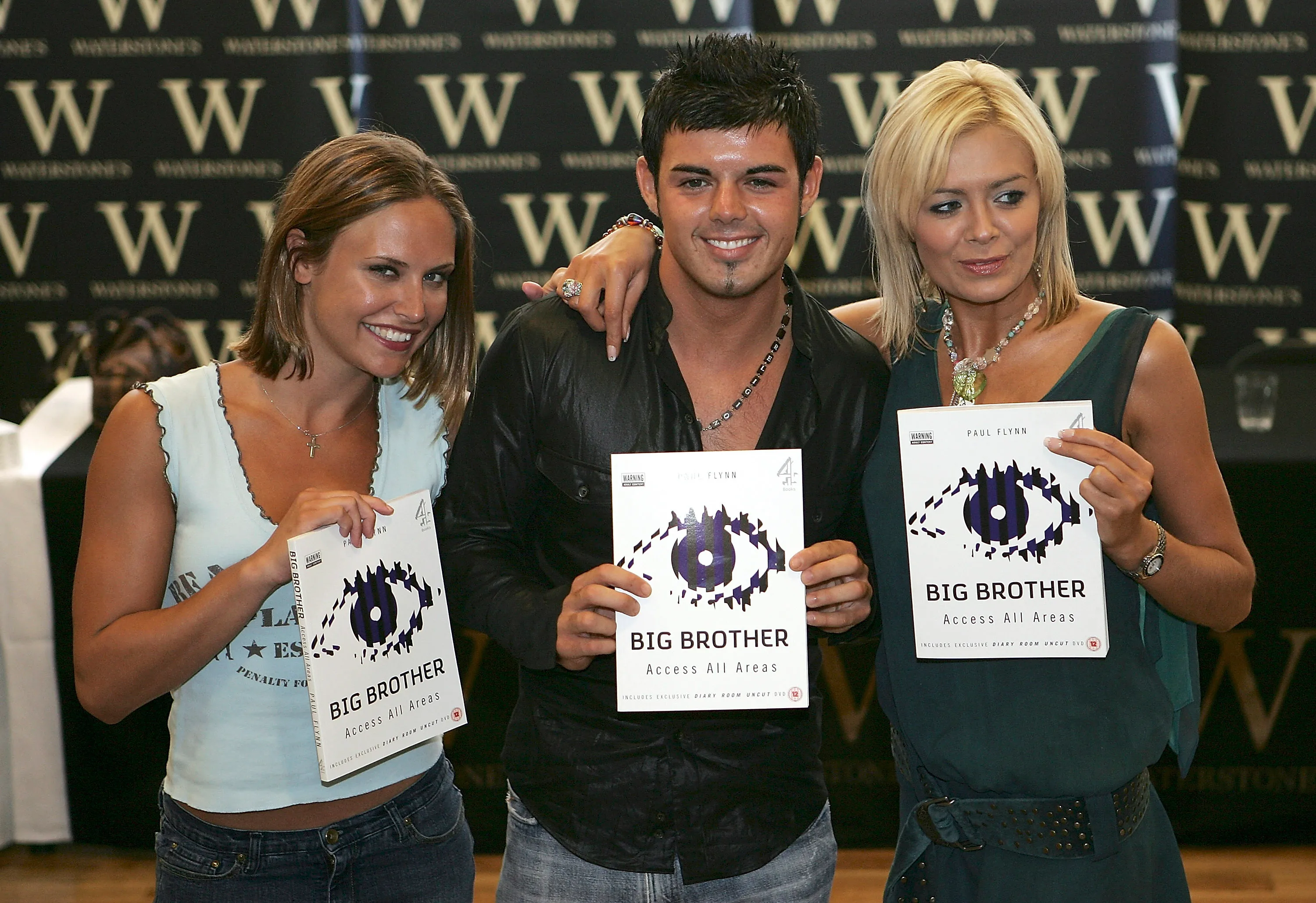

At its peak, Big Brother drew 14 million viewers (Picture: MJ Kim/Getty Images)

Over the summer this year, I had one foot in the Big Brother house – and the other in every ex-housemate’s DMs.

Having been invited to go on the show, and unsure about whether I should take the plunge, I decided to ask previous contestants for advice.

One message became two, two became 10, 10 became a list, and before long I was contacting every contestant ever. Over 350 of them.

I made a spreadsheet, obviously. Some were easy to track down, some have completely vanished from public life.

The stories were very different, even if some themes (editing complaints, relentless boredom, the sheer grimness of how the shared bedroom smelled) emerged, but every person was unique.

Together, they chart a story of Britain – the good and the bad – played out on television through one of the country’s biggest cultural phenomena, which at its peak drew 14 million viewers, and almost drew me into the house itself.

When Big Brother exploded onto British television in 2000, the biggest storyline was ‘Nasty’ Nick Bateman, who was ejected from the house for his attempts to influence nominations by passing notes to his fellow contestants to try and determine their voting intentions, breaking a cardinal rule that is still enforced today.

Twenty-five years on, when I contacted him via a simple Instagram message, he told me the real hardship wasn’t the scandal but the grind of the house, talking of his ‘boredom, and lack of stimulation.’

Former housemates (R-L) Anouska Golebiewski, Jade Goody, Narinder Kaur, Melanie Hill, Nick Bateman, Kitten, Victor Ebuwa, Tim Culley, Marco Sabba and Spencer Smith (Picture: Channel 4 via Getty Images)

Andrew Davidson, one of the very first housemates in 2000, took some time to track down. I eventually went via a friend’s Linkedin post which took me to his old business website, which took me to his new one, where I managed to find an email. Even he was impressed: ‘blimey, good research finding me!’

He said it was strangely liberating: ‘Freedom from work, responsibilities, relationships, social norms, all of it – we all just went a bit mental, as shown by the naked pottery a few days in.’

By 2005 Big Brother had become Channel 4’s flagship show, with episodes doubled from 52 to 90, later peaking at 108. Anthony Hutton – that year’s winner thanks to the same everyman charm that was still present when I spoke to him – said the moment Davina read out his name was ‘the greatest night of my life.’

Anthony Hutton was the 2005 winner thanks to his everyman charm (Picture: Gareth Cattermole/Getty Images)

But others barely got started. Bonnie Holt, who was the first evicted housemate in 2006 after barely a week on screen, told me her favourite memory was simply walking through the doors.

That same year, Pete Bennett, whose Tourette’s Syndrome and naked antics made him a household name, said he was glad to have raised awareness of his condition.

But he also recalled how the edit skewed things. ‘Mikey got his k**b out first … then egged me on. When I watched [it] back, he’s cut out and I look like the only one splashing my w**g about.’

Pete Bennett was glad to raise awareness of Tourette’s Syndrome (Picture: Chris Jackson/Getty Images)

Editing is something almost every housemate raises, with some claiming it renders conversations and situations completely unrecognisable from reality. Lisa Jeynes from 2003 told me it was ‘bittersweet,’ because ‘the edit didn’t show the fun side of me in the house.’

Environmental activist Daze Aghaji, who entered in 2023, is unconvinced by the show: ‘It’s marketed as a social experiment yet it lacks all the best bits of an experiment like fairness. I’ve campaigned against the government, slept on the streets for two weeks, engaged in active rebellion… Big Brother was tougher.’

And for many, the hardest part came later. Davidson told me one of his lowest moments was ‘being asked for my autograph whilst trying to get a job in a call centre – and then finding out I didn’t get the job.’

Big Brother at this stage was messy, unscripted, and oddly profound

Vanessa Nimmo, from 2004, said she’d always wondered what fame would be like, but now ‘wouldn’t wish it on my worst enemy. It’s definitely overrated and a huge invasion of privacy.’

Some never even watched their own series back, fearing it would be too distressing. Freddie Fisher – remembered by fans as ‘Halfwit’ after he had to legally change his name during a task – described his 10 weeks as ‘like 10 months.’ He’s glad he did it, but admitted: ‘My mental health suffered. There were some dark times, but I grew a lot as a person.’

Glyn Wise, who came second in 2006 as an 18-year-old lifeguard, still laughs about the summer Britain watched him learn to boil an egg. ‘Too many favourite moments to count,’ he said, ‘but I walked out a boy and came out a man.’

Big Brother at this stage was messy, unscripted, and oddly profound. It made villains, it made underdog heroes, and it showed ‘ordinary’ people in extraordinary detail.

By the late 2000s, Big Brother had tilted fully into soap opera, but speaking to former housemates makes clear the impulse was always there. Nick Bateman was cast as the first villain in 2000, yet by the end of that decade the archetypes felt industrialised – twists multiplied, love triangles and feuds became the story, and the edit carried more weight as live feed was cut back.

Several told me they saw cartoons of themselves on screen. What really changed was the world outside: Liam McGough, who came third in 2007, said he was glad he did it, but wouldn’t repeat the experience in today’s climate: ‘I went in pre-social media and today I wouldn’t enjoy inviting the world into my home.’

Glyn Wise came second in 2006 as an 18-year-old lifeguard (Picture: Chris Jackson/Getty Images)

Later contestants describe pile-ons, memes and clips that never faded. Producers didn’t stop making villains, but print tabloids were replaced by social media that immortalised them – and made the consequences far darker. Many housemates reported death threats.

Rebeckah Vaughan, who entered in 2011, told me: ‘I didn’t expect the edit to be so bad – I was vilified.’

Dexter Koh told me ‘the bedroom was a cross between a French cheese factory and a Victorian bordello’ (Picture: Karwai Tang/WireImage)

Some things continued to remain constant, like the sensory experience. 2013 runner-up Dexter Koh told me ‘the bedroom was a cross between a French cheese factory and a Victorian bordello – like entering the backdraft of desperation and decaying dignity.’

As ratings dropped in the early to mid-2010s, it started to feel to even fans like me that Big Brother wasn’t just reflecting Britain – it was manipulating it. Producers built pantomime villains, the tabloids amplified them, and contestants were left to carry the weight – and some couldn’t cope.

‘It ruined everything. I lost everything,’ confessed one former housemate from a later series who wanted to remain anonymous. ‘My marriage, my career, my friends – I’m still piecing my life back together.’

A finalist from 2015, Danny Wisker admitted the show left a deep mark: ‘I became an introvert, socially awkward.’ Despite reaching the final, he ‘found the experience mentally challenging’ and ‘really struggled after the show.’

Danny Wisker admitted the show left a deep mark (Picture: Karwai Tang/WireImage)

That year’s designated hunk, Marc O’Neill, struggled with ‘intense attention.’ He told me he wouldn’t do it now. ‘Life’s different … I’m a scientist, I’ve matured (a little anyway), and my little boy is my world.’

Yet there were still highs in those later years. 2018 winner, Cameron Cole, came out as gay during the show, telling me: ‘It was the happiest and safest I’ve ever felt… Would I do it again? Absolutely.’

When ITV revived the format in 2023, it tried to balance nostalgia with relevance. Trish Balusa became its most controversial star, unafraid to call out sexism, racism and the limits of the format, before having to apologise for ableist, racist and anti-LGBT tweets.

She was blunt with me: ‘I didn’t expect producers of a social experiment to avoid hard conversations. It makes it pointless. It’s just volunteering to be exploited.’

Out of the 359 people I attempted to reach out to, many have left no trace

Her experience, in and out of the house, captures what Big Brother has become in a new era: sharper, more political, more divisive – but still capable of sparking national debate.

I was tempted because of that same sharpness; the idea that Big Brother still reflects the country back at itself, messy but unfiltered, and that you can take part in something that still has cultural weight a quarter of a century on. Trish’s experience didn’t dissuade me so much as underline the risk.

She was right about the exploitation and the backlash, but that’s also the point: Big Brother is only ever as interesting as the uncomfortable conversations it forces into the open. That tension – between wanting to be part of the debate and knowing how bruising it can be – is exactly why I got so close to saying yes.

But what struck me most wasn’t just the stories I did hear but the silence from those I couldn’t.

The bedroom for Big Brother 2001 contestants (Picture: Dave Hogan/Getty Images)

Out of the 359 people I attempted to reach out to, many have left no trace. Over a third refused to talk or simply didn’t respond.

Fame arrived like fireworks – dazzling, noisy, unforgettable – and then disappeared. One week it was breakfast TV sofas and nightclub appearances; the next it was awkward stares in a supermarket; soon after, nothing at all.

After hearing from winners, villains, icons and obscurities, I was struck by the same themes repeating.

The edit is always a sketch, never a portrait. Duty of care has somewhat improved, but the internet is crueller. Old clips live forever, and defending yourself online only feeds the algorithm.

And class runs through it all. Big Brother gave working-class contestants microphones, then often mocked them for using them. ‘People loved the accent until it said something they didn’t like,’ one contestant told me. Britain celebrated ‘ordinary’ voices, but only on its own terms.

What housemates themselves remember most aren’t the rows or the fame but the small absurdities: the puppets, the pantomime horse, the kettle that sounded like an aeroplane, the sleep-deprivation punishments. These fragments – bizarre, human, funny – are what 25 years in a glass box really left behind.

Comment nowWould you have taken the opportunity to join Big Brother? Share your thoughts below!Comment Now

What drew me close to saying yes wasn’t the lure of fame or even the oddball tasks, but the sense that Big Brother still says something about the politics of now.

As a political advisor, it’s my job to understand the climate and I am fascinated by why someone like Nigel Farage can harness the rhythms of reality television, why ordinary voices can be turned into pantomime villains or folk heroes, and how that shapes the way Britain sees itself. I thought the house might be a laboratory for understanding that.

But the more I spoke to past contestants, the more I realised the experiment had already been run. They’d lived the costs and the contradictions. Their stories made me understand that what I was searching for – why Britain keeps electing its villains, why we fall for easy storylines – was already written in two decades of footage and memories.

So I pulled out – and despite everything I’d heard, it was a hard decision.

Big Brother was never just about the house, it was Britain looking at itself in a mirror. On this occasion, I couldn’t risk everything to step inside to see what it was reflecting.

Do you have a story you’d like to share? Get in touch by emailing jess.austin@metro.co.uk.

Share your views in the comments below.