Senior Trump administration health officials spent days devising the delicate rollout of new guidance suggesting a possible link between autism and the usage of acetaminophen, the active ingredient in Tylenol.

But all their careful plotting could not account for one key variable: President Donald Trump.

Trump on Monday steamrolled his health department’s plans to announce a nuanced step toward addressing rising autism rates, seizing on the first possible solution to declare a victory over a scientific question that has captivated him for decades, four administration officials and close advisers said.

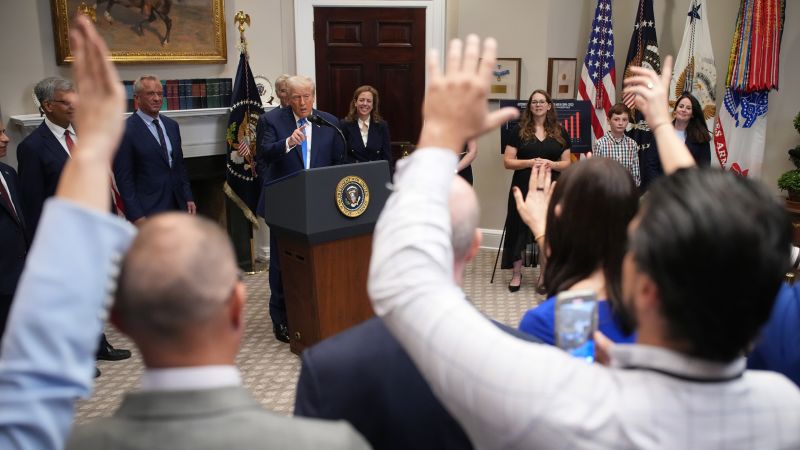

“I’ve been waiting for this meeting for 20 years,” Trump said from the Roosevelt Room. “I always had very strong feelings about autism and how it happened and where it came from.”

The president went on to promote a range of unproven theories and musings about autism, Tylenol and vaccines. He urged pregnant women to “tough it out” rather than take acetaminophen except in extremely rare cases, aired doubts about widely accepted childhood immunizations and repeated an oft-told story about a former employee’s child who came down with a fever after vaccination and was “lost” to autism shortly after. Extensive research has failed to establish a causal link between vaccines and autism.

The rambling display stunned administration officials who had expected the event to highlight a cautious new warning on Tylenol, $50 million investment in further autism research and approval of a potential treatment — only to watch Trump declare that “taking Tylenol is not good” and then veer into vaccine skepticism, two officials familiar with the matter said.

The administration officials and advisers privately acknowledged that the president’s blanket assertions had gone well beyond the underlying evidence he’d been presented with in prior days, turning what health officials had termed a possible “association” between Tylenol use during pregnancy and higher autism rates into a definitive causal link — and then proclaiming that flawed conclusion from the West Wing.

At the same time, though, they sought to downplay the episode, arguing that Trump, at the very least, had drawn attention to the administration’s autism work. They attributed his bombast to his personal fixation on autism and its causes, harbored since well before he entered presidential politics.

“He has his own speaking style and communications style, and that’s part of the authenticity,” said one White House official.

The performance has alarmed autism researchers and public health experts who held out some hope that the administration would pursue a serious and extended inquiry into autism. They warned in the aftermath that Trump’s rhetoric would only end up further confusing parents already anxious over the condition and complicate doctors’ efforts to manage the risks of pregnancy.

“To tell women that the one option they had available to them shouldn’t be available to them could potentially be very problematic,” said Joshua Anbar, an Arizona State University professor who specializes in autism and has a background in child and maternal health. “Before making those kinds of recommendations, we should be very sure in what benefits we could receive.”

Ashish Jha, the dean of Brown University’s School of Public Health and a former senior Biden administration health official, put it more bluntly: “That was possibly the worst public health press conference I have ever seen in my life.”

In a statement, White House press secretary Karoline Leavitt said the administration “does not believe popping more pills is always the answer for better health.”

“There is mounting evidence finding a connection between acetaminophen use during pregnancy and autism, and that’s why the Administration is courageously issuing this new health guidance,” she said.

Trump and vaccine skepticism

Monday’s extraordinary announcement represented the culmination of years of anticipation for Trump, who has long speculated on the causes of autism and expressed openness to a range of pseudo-scientific theories.

The president has often floated the possibility that childhood vaccinations are linked to autism in some way, an assertion that he resurfaced at length on Monday to the surprise of aides who had not expected vaccines to be part of a discussion meant to focus on acetaminophen, two officials said.

“Bobby wants to be very careful with what he says,” Trump said, gesturing to US Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. “And he should, but I’m not so careful with what I say.”

The interest is in part a personal one that dates back to the early 2000s, allies and advisers said, driven by his observations of friends with autistic children and his own experiences as a parent. After one friend, former NBCUniversal chairman Bob Wright, founded the advocacy organization Autism Speaks following his grandson’s diagnosis, Trump hosted fundraisers for the foundation at Mar-a-Lago. He began publicly theorizing about a connection between autism and vaccines during that period, reportedly saying in 2007: “My theory is the shots.”

The president also talked about vaccinating his son, Barron, and suggested he had delayed certain immunizations due to worries that it could lead to autism.

“He had real concerns about vaccines,” said one adviser. “The president comes into this with skepticism.”

Trump sought to explore the issue in his first term but was deterred by aides’ worries about the political sensitivity of the matter, and their fears about the risk of amplifying his suggestions that autism was connected to vaccines, advisers said.

He returned to office this year unencumbered by those conventional restraints — and in Kennedy, he found a health secretary who shared his conviction for finding a singular cause of autism, regardless of the widely held belief in the scientific community that the rise in autism is likely fueled by a combination of genetic and environmental factors as well as better diagnoses.

Kennedy has vowed to prioritize a wide-ranging initiative aimed at finding the potential drivers of its increasing frequency in children.

During a Cabinet meeting in April, he pledged to deliver definitive answers within five months.

In reality, the Department of Health and Human Services had planned only to make a first round of funding awards to autism researchers by September.

But Trump latched onto the promise, pressing his top health officials for answers and repeatedly teasing the announcement in public.

“I think we maybe know the reason,” Trump said in August. “And I look forward to being with you in that press conference. That’s going to be a great thing.”

The president’s enthusiasm prompted a scramble within HHS in the weeks ahead of Monday’s event, with officials debating what they could deliver and how significantly they would need to caveat conclusions.

The department’s message on Monday, in contrast to what the president presented, was meant to be measured and carefully worded, suggesting a “potential association” between Tylenol use during pregnancy and autism based on a review of existing research.

Speaking after Trump at the press conference, Kennedy also acknowledged “contrary studies that show no association” and that there’s no better alternative for managing fever and pain during pregnancy.

“Given the conflicting literature and lack of clear causal evidence, HHS wants to encourage clinicians to exercise their best judgment in use of acetaminophen,” HHS said in a statement that promised further research toward better understanding autism.

Andrew Nixon, the HHS spokesperson, told CNN that Trump and Kennedy would “remain focused on uncovering the root cause of the chronic disease crisis, especially in our children.”

Yet on Monday, as Kennedy and his top deputies stood by, Trump abandoned any sense of that caution and complexity in favor of delivering the kind of simple conclusion he’d craved for years.

“The way I look at it, don’t take it,” Trump said, referring to Tylenol.

“I’m not a doctor,” he added. “But I’m giving my opinion.”