Copyright ncregister

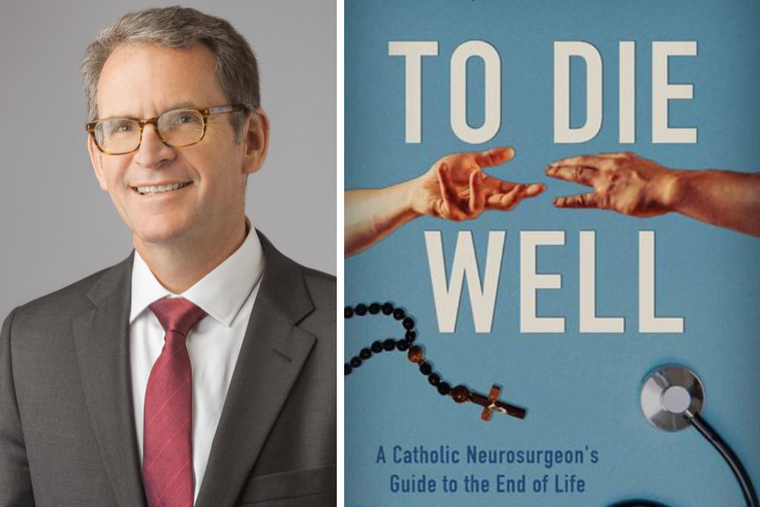

Dr. Stephen Doran of Omaha, Nebraska, has seen people die well and people die poorly during his more than 25 years as a neurosurgeon. Doran, 62, who was ordained a Roman Catholic deacon in 2021, chronicles both types of exits and offers advice to fellow Catholics for how they can follow the Church’s teachings and prepare to meet their Maker in his 2023 book, To Die Well: A Catholic Neurosurgeon’s Guide to the End of Life, published by Ignatius Press. Some people, like his father-in-law, Mike Lewandowski, who had terminal leukemia at age 70, died at peace “because the spiritual realities of death were not pushed aside but embraced, welcomed — not only by Mike, but also by his family,” Doran writes. Others, like a patient he calls Zach, neglected physical and spiritual needs as their terminal illness progressed and died without joy. How does one die well? A lot of it, he says, comes down to preparation — death is coming for all of us, so don’t let it take you by surprise. Among other things, he recommends appointing a durable power of attorney for health care whom you trust to make medical decisions for you in case you can’t make your wishes known. He spoke with the Register on Oct. 21. Many people whose loved ones are dying are confronted near the end with a myriad of drugs they’ve never heard of and treatment options they don’t understand. Is there more the Catholic Church can do to help people make the right decisions in a time of sadness and stress? The Catholic Church and, quite honestly, the medical community can do a better job of encouraging people to think about this in advance. You’re never going to be able to anticipate all the possible events that might occur, but you’d be surprised how many people I’ve run into — family members or the patients themselves — who are facing a critical illness or stroke or something like that, and we’re getting down to talking about treatment options and continuing care and things like that, and they just say, “Well, we’ve really never talked about this before.” And this might be somebody who’s really quite advanced in age. And so I think, from a pragmatic perspective, just bringing it up and thinking about it, but also from a spiritual perspective to really start contemplating that there’s something else out there, beyond our lives here. Pope Pius XII, in a speech in 1957 called “The Prolongation of Life,” made a distinction between ordinary means of treatment to prolong life, which he said are morally necessary, and extraordinary means, which aren’t morally necessary. You quote it in your book. But you also say in your book: “It is important to realize that there is not a ‘list’ of treatments that can be cleanly divided into ordinary and extraordinary.” How can Catholics who aren’t experts make the right decisions about what they should and shouldn’t do at the end of life? These are complicated things, and even within the same patient what was once ordinary can become extraordinary in the course of treatment; classic example is someone who has cancer. It’s ordinary treatment, you might say, to treat it initially. But as the cancer progresses, it becomes futile, and it becomes extraordinary to treat it the same way. So it’s ongoing conversations. But I think the big problem that we have in medicine is this: the depersonalization of medicine. I think it’s the root of so many things, where patients are now kind of perceived as a problem to be solved, instead of a person. And so, it becomes much easier to focus on the disease process than it is to the person themselves. Don’t be afraid to say, “I need time. Let’s come back and talk about this later.” And bring in people who know you, who love you, who understand your morals, who are faithful to the Church’s teaching, to help guide you through this. We hear a lot about living wills and the importance of having them. In the book, you contend that living wills ought to be discouraged, and you argue that a more formal document called “Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment” is even worse. What, in your view, are the pitfalls of these documents, and what should a Catholic do instead? I think, No. 1, everybody should have a durable power of attorney for medical health care, regardless of whether you have a living will or not. I really think that’s all you need. But that means you’re going to have to talk to that person and explain to them what your desires are and how you hope to have that process go at the end of life. If someone really feels that they need a living will, it really should be very open-ended in the sense that, “If there’s a situation where prolonged treatment really is not going to realistically extend my life in a substantial way, and it could only potentially extend suffering, then I would choose not to pursue that treatment.” But as soon as you start saying, “Well, I don’t want to have chemotherapy for cancer, I don’t want to be on a ventilator, I don’t want to be intubated,” that can be dangerous. The circumstances that may happen are so difficult to anticipate. It can be very complicated. And so to try to write down or have directions that are going to be able to address the complexities that might be present, that’s really difficult to do, if not impossible. So that’s why a list of do-this-and-do-that, or don’t-do-this-and-don’t-do-that, really, I think, can almost in some ways either be meaningless or is harmful, depending on what’s going on. Many people worry about end-of-life suffering, but you say in the book that a drawn-out dying process is not necessarily a bad thing. You write that “this is a sacred time, the transition between full awareness and unresponsiveness. It is a time not to be rushed. It is a time to savor.” Why is that? This is one of the most personal experiences that I’ve had. And I’m not going to try to pretend that every prolonged experience is easy or necessarily something you have to savor. But it can be, it really can. There’s a lot that goes on with the person who’s dying. There’s a lot that goes on for the people accompanying them. And I’m not saying that you drag things out, in some sort of masochistic fashion. That’s not appropriate either. But don’t be afraid to stay with something. I mean, just in general, in our lives, in our prayer lives, stay with it. And if that means someone’s dying, stay with it. You know, it’s hard. It’s sad. It’s uncomfortable. And, ultimately, at the end, we want to honor what the individual’s desires are, assuming that they’re appropriate and moral. But don’t have the default be, “Let’s get this over with.” That can’t be the default. Why is it important to die well? Because it reflects a desire to live well, which means a desire to conform our lives to Christ.