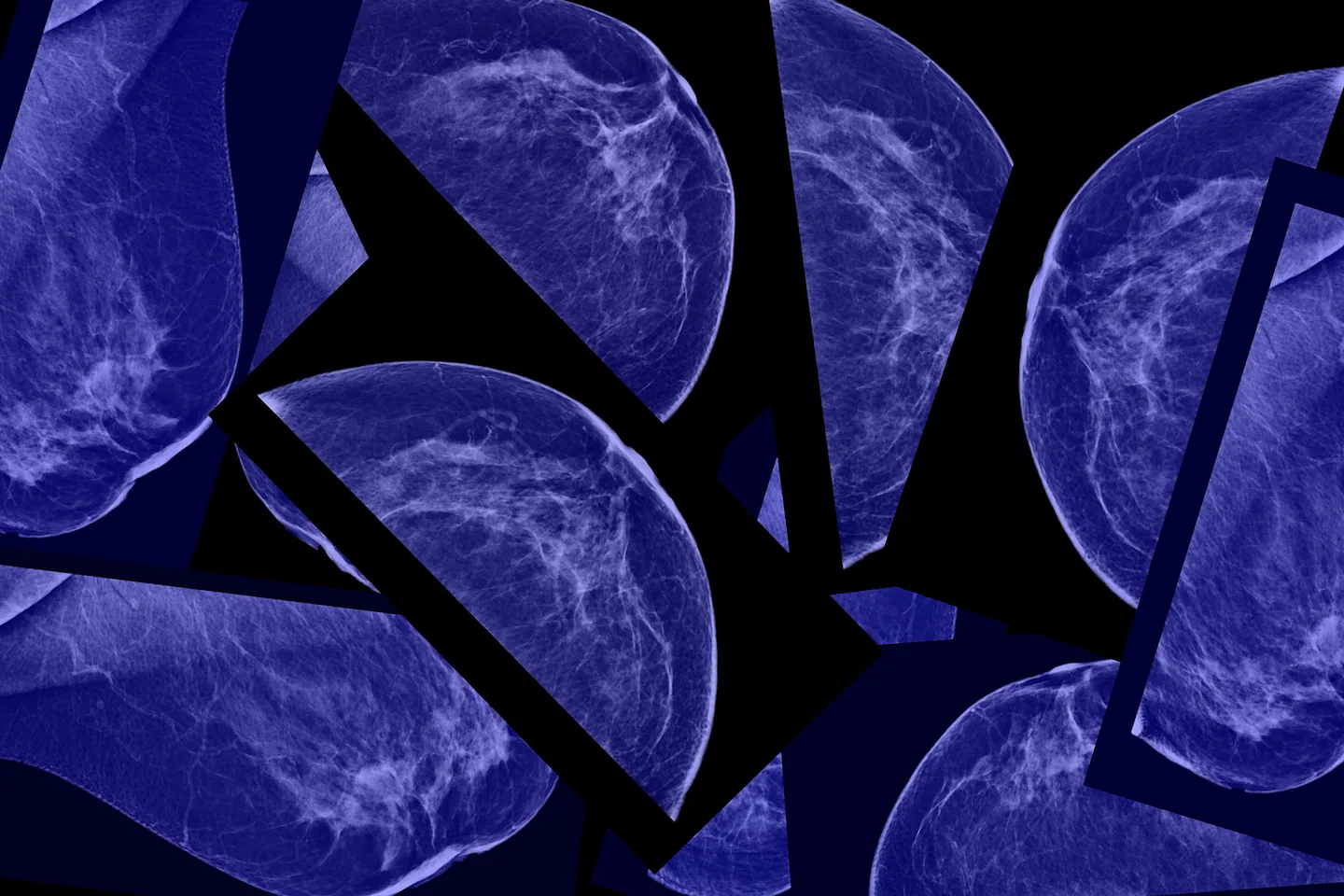

There’s some good news, though: Breast cancer deaths fell about 44 percent between 1989 and 2022, thanks to better screening techniques and treatments.

Right now, I know eight women with breast cancer. Most are doing fine. But a mom in my neighborhood also recently died of the disease, leaving behind a high-schooler. The possibility of breast cancer haunts me, and it haunts so many women I know.

The idea of going for a mammogram and anxiously waiting for portal results — refresh, refresh, refresh — is terrifying. I also know that I need to get over it: The US Preventive Task Force says that regular mammograms to screen for breast cancer should start at 40. After my colleague Shirley Leung went public about her diagnosis, I remember texting her something like: I’m so proud of you. I want to be brave, too.

Dr. Dana Xu, a breast surgeon at Emerson Health in Concord — who also recently underwent her first screening mammogram — wants to reassure women like me, who fear being sucked into a refresh spiral: What if you’re called back? What if you enter a panicky limbo of testing and vigilance?

According to Johns Hopkins Medicine, about 1 in 10 mammograms results in a callback. But in about 90 percent of these cases, further testing reveals nothing serious.

“And, if it is something dangerous, we’re catching it when it’s early and eminently treatable,” Xu says.

Here’s what she wants women like me, and maybe like you, to know about getting screened.

Keep perspective. Lots of it. Even in the worst-case scenario, if a screening mammogram picks up cancer, it’s probably very treatable. Remember that.

“Oftentimes, I tell my patients that, [if] you get that diagnosis, the majority of the time, it’s not: ‘This is the end.’ … The majority of breast cancers picked up in a routine screening are stage 1, and survival rates from stage 1 breast cancers are 98 percent,” Xu says.

Know your BI-RADS score. BI-RADS stands for the Breast Imaging-Reporting and Data System. The system sorts mammogram results into numbered categories.

“The BI-RADs score is: How suspicious does the radiologist think it is?” Xu explains.

A score of 0 means there’s not enough information to make a determination, so you might be called back for more imaging; 1 means nothing suspicious is seen; 2 means something is seen, but it’s almost certainly benign and no action needs to be taken. (My score is 2 because I have scarring from breast-reduction surgery. This was discovered on my last mammogram, which was too long ago.)

Category 3 warrants watchful waiting. Many women are asked to come back in three to six months to check for changes. Don’t panic, though. Many things that radiologists see on a mammogram are harmless, such as stroma (connective tissue), lobules (milk-producing glands), ducts, blood vessels, or cysts — all normal stuff inside our boobs.

Sometimes, a radiologist will also see calcium deposits. Chunkier ones are often benign. Smaller clusters could indicate abnormal cell growth and are often monitored.

“It’s the fours and the fives that can kind of scare patients a little bit,” Xu says, but even those results can be well-managed.

With a 4, “That means we see something there, and it’s suspicious. This could be something. We shouldn’t wait and get another picture in several months. We should just take a little piece of it right now; we should biopsy it,” she says.

A score of 5 is highly suspicious for cancer. More on that in a moment.

Your mammogram might indicate that you have dense breasts. That’s normal. In the BI-RADS analysis, your mammogram will categorize the density of your breast tissue. Dense breasts are a common, often harmless finding. Denser breasts often lead to more callbacks and ultrasounds because findings are harder to interpret, but they don’t mean you have or will get cancer.

“Ninety percent of the population has some level of lumps,” Xu says. “It is exceptionally, exceptionally common and not necessarily dangerous in any way, shape, or form.”

Densities refer to stroma, vessels, and other non-fatty tissues: natural, normal, not dangerous. These show up as white spots on a mammogram. There are four classifications, ranging from most fatty to most dense.

Grade A indicates mainly fatty tissue, and it’s a relatively rare finding. Grade B indicates scattered fibrous, glandular densities, which show up as white areas on a mammogram. This is a typical finding.

“This means we see little chunks of areas that are a little bit brighter. That’s about 40 percent of the population,” Xu says.

Grade C indicates that breasts are “heterogeneously dense.”

This wording “tends to scare patients the most,” she says, even though it’s also common. It doesn’t mean that cancer is lurking in your cells.

Grade D patients have “extremely dense” breast tissue. They account for about 10 percent of people, she says. This category indicates a slightly increased lifetime risk for breast cancer. But it’s not a malignant finding on its own.

Everybody thinks ‘Oh, no. I’m alone in having dense breasts.’ You are not alone,” Xu says. Dense breasts are “just a radiologic finding [indicating] how much stuff [other than fat] is in your breasts.”

Density often morphs over time, too, which is why it’s important to keep current on mammograms to monitor patterns and changes.

“When you’re younger, you’re going to have denser breasts. With age, with hormone changes, with pregnancy, with breastfeeding, everything within the breast changes. Typically, as you get older, your breasts get less dense,” she says.

Try not to catastrophize if you’re called back for more imaging. Terrifying! But remember: Dense breasts can be harder to analyze. Often, women will be called back for a diagnostic mammogram, which also includes an ultrasound and potentially a biopsy, where a sample of tissue is excised from the breast and analyzed to check for suspicious cells. This isn’t ominous; it’s a precaution.

Xu often sees patients in between an ultrasound — a more focused look at a suspicious area — and a biopsy, a stressful limbo during which she aims for reassurance.

“Just because they find something on your mammogram doesn’t mean it actually is anything. Just because we see a lesion on the ultrasound doesn’t mean that it actually is a cancer,” Xu says.

“We see a whole spectrum of benign lesions that do not increase your risk of breast cancer,” she says, such as ductal atypia, abnormal cells in milk ducts that should be monitored for future risk but aren’t yet cancer.

MRIs are helpful, but they’re not for everyone. It’s tempting to want magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), an ultra-detailed imaging test. It’s highly sensitive, but it can also be unnecessarily anxiety-provoking for women with average risk because it can pick up harmless, incidental findings.

“The MRI is a wonderful tool. It’s very sensitive, which means that, if there is something there, the MRI more likely or not is going to pick it up. But the MRI is also a very expensive and very uncomfortable procedure that can be absolute overkill, because the MRI isn’t very specific. If you’re somebody who’s already getting anxious just from a mammogram, can you imagine getting an MRI, where you’re very likely to pick up something?” Xu asks.

“It significantly increases your chance of having a negative biopsy and more procedures than you truly need,” she says.

That said: Xu emphasizes that MRIs are important for patients who have a lifetime breast cancer risk above 20 percent.

Xu recommends the Tyrer-Cuzick assessment model to estimate breast cancer risk, which takes into account factors such as age, height, weight, family history, age at first menstrual period, and more. Talk to your doctor about it.

Please don’t ignore the screening mammograms. “They’re annoying, they’re uncomfortable, and sometimes they can be very anxiety-provoking. Just because you find something on your screening mammogram doesn’t mean it’s anything dangerous,” Xu says.

And reward yourself when you’re done — with a treat, a drink, a triumphant group text.

“When I got my first screening mammogram, I screenshot that thing and sent it to all my girlfriends,” Xu says.

There’s lots of hope for breast cancer patients. Of course, a screening mammogram might unearth breast cancer. But catching it early is the best defense.

“You’re not alone, and there’s a very good support system out there for managing this. There’s a very well-established protocol,” Xu says.

“[We] know what the next steps are. So much of medicine is annoyingly, ‘hurry up and wait.’ That waiting period is so anxiety-producing, so frustrating. I’m sorry for that. But, at the end of the day, just because it is something, if you’re finding it on your screening — even in the worst-case scenario, for the majority of the time, you’re catching it early and doing the right thing. You’re going to be able to take care of it. Is it annoying? Yes. Is it devastating? No.”

After talking to Xu, I gave myself a stern lecture, because I’ve postponed my next mammogram long enough. And the longer I wait, the scarier it becomes. Best to get it done with. (And shout-out to my dear friend Jen, who has long offered to drive me to the appointment.)

“Take a deep breath. Hold somebody’s hand. It can just be a technician’s hand. I can’t guarantee you’ll be OK, but you’re going to be better than if you don’t do it,” Xu says.