Copyright STAT

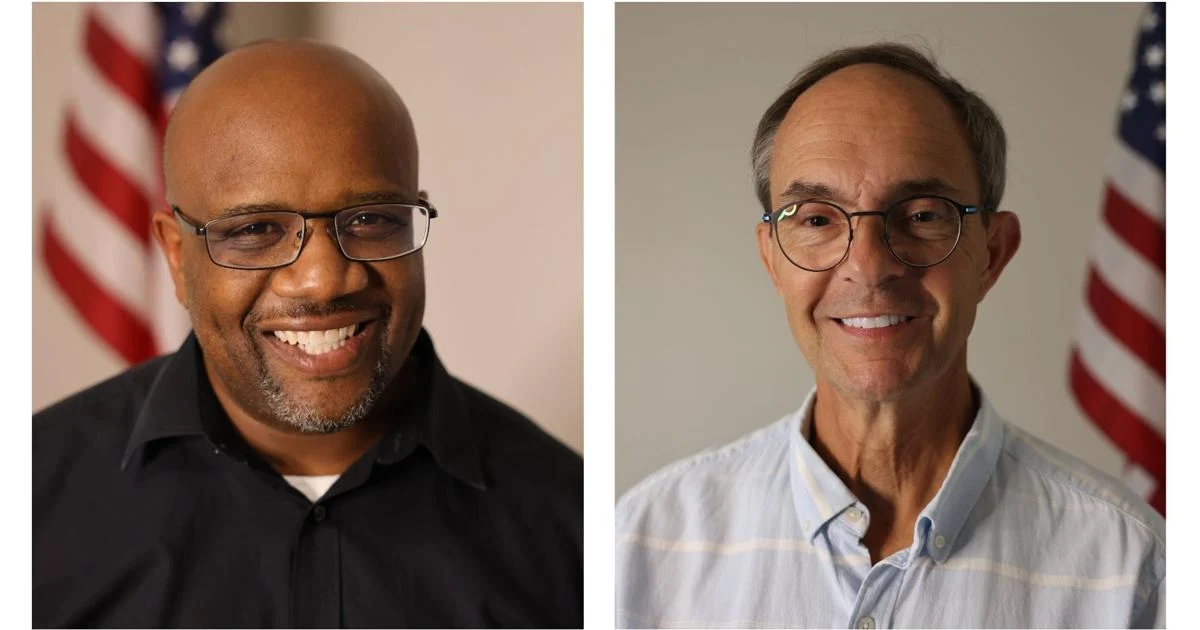

AUSTIN, Texas — California has long been considered a kind of political fortuneteller, offering a preview of the policies that later emerge elsewhere in the country, and in Washington. But in the age of Trump 2.0 and the Make America Healthy Again movement, Texas is the place to look. With its diverse population, a political establishment eager to please the Trump administration, and a cabal of prominent MAHA converts, the state has become a testing ground for a spate of health-related legislative efforts in recent months. Those moves center on everything from looser school vaccine requirements to bans on fluoridated drinking water, mandatory nutrition courses for doctors, new food labels — and beyond. Advertisement It’s a good place to see where rubber meets the road, too. In Texas, the second-largest state by size and population, MAHA dreams are up against big-state complications, including industry interests and inequities in access to quality health care and food. Like much of the country, Texas has room to improve in health care. Inequality here starts at birth: Nearly half of the state’s counties are considered maternity care deserts, according to a 2024 analysis from the March of Dimes. Texans struggle to stay healthy into adulthood, too. On average, the prevalence of all chronic conditions in the state was nearly 14% in recent years, higher than in other large states such as Alaska, Florida, and California. Over one-third of adults in Texas have obesity, and hospitalizations for diabetes alone cost Texas $5 billion annually, per state estimates. An August poll from the University of Texas at Austin found health care was a top worry for respondents, with 63% saying they were very concerned about costs. Advertisement These problems persist, with some variation, whether one is in deep-red MAGA country or blue hubs like Dallas and Austin. Despite those progressive city voters, Trump won the state with 56.3% of the vote in 2024. Republicans have won Texas in every presidential election since Jimmy Carter carried it five decades ago. These days, chatter in Washington doesn’t always penetrate people’s consciousness. During a STAT reporter’s weeklong trip through the heart of the state in late September, Texans expressed limited familiarity with Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. and even less awareness of his MAHA movement. But their everyday concerns echoed those of Americans nationwide. Many spoke about trying to stretch their money and time to prepare home-cooked meals, or avoiding health-harming foods and chemicals. Others said they struggled to get thorough health care when they needed it from a provider they trusted. Most were wading through vast amounts of information online, and — above all — just trying to keep their families healthy. “A lot of people don’t even complain about it because they don’t feel that anything is ever going to be done,” said Ishmael Harris, mayor of Bastrop, a small city outside of Austin. He is advocating for a regional hospital in his rural area. Others talked about what they saw as a lack of humanity in the current health care system, medicine’s overreliance on pharmaceuticals, and corporate interests causing their ill health. Much of what people had picked up on lately when it comes to health and wellness came from short snippets on social media; distrust in the mainstream press abounded. A ‘laboratory’ for MAHA The average Texan may not know MAHA by name, but the movement has undoubtedly taken root here. In late August, Gov. Greg Abbott (R), a close ally of President Trump’s, sat shoulder to shoulder with Kennedy as he signed a package of MAHA bills at a desk adorned with a blue placard reading “Making Texas Healthier.” “I’m really happy to be here in Austin today for this historic occasion that puts Texas, once again, ahead of the nation in leadership,” Kennedy said, adding that no state, “with the possible exception of Louisiana,” had gotten more robust MAHA legislation passed. Advertisement The legislation mandates that schoolchildren receive at least a half-hour of physical activity every day and are offered nutrition education. The law also says all aspiring health care workers and physicians seeking to renew their licenses will have to complete courses on nutrition. Other legislation establishes new food labeling requirements, bans artificial food dyes and additives in low-cost school meals, and pulls sugary drinks and candy out of the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP). A key part of the MAHA movement’s strategy so far has been developing laws in states — “laboratories of innovation,” as Agriculture Secretary Brooke Rollins has called them — in order to create a groundswell of pressure and push companies into changing their practices without the need for federal regulation. Texas, as a red state deeply allied with Trump, quickly complied with that formula. Even before its big MAHA package, the state passed bans on lab-grown meat and cellphones in schools, other matters the administration cares about. Other states have passed a crush of MAHA bills this year as well, all inspired or encouraged by allies of the health secretary. Mostly, they have been championed by Republicans, who want to please the president and see MAHA as a winning political issue for core and swing voters. Midterm elections could be a referendum on that idea, especially as Kennedy struggles to maintain popular support. Political moments like MAHA get “two to four years — maybe six, if you’re lucky — before they float out of the popular lexicon,” Travis McCormick, an Austin-based political consultant and an architect of key MAHA legislation, told STAT. He has started a political action committee, Make Texans Healthy Again, to advance more bills next session. Differing views on administration priorities Such political calculations are of little import to most Texans. But debate about certain health issues still gets through to even the most news-averse. In late September, it was nearly impossible to ignore Trump’s claim that Tylenol use during pregnancy may cause autism spectrum disorder — and his exhortation to parents to avoid brand-name acetaminophen while offering little evidence to support his plea. Advertisement Amber Bogie, 36, had just seen the news that morning, a few days after Trump’s press conference about autism. As a new mom, the Austin-based tech marketer avoids social media for her own well-being. “I took Tylenol, like, three times while I was pregnant, so I think I’m in the clear,” she said. Alysha Bogie, Amber’s 39-year-old sister, on the other hand, was very tuned in. She manages Ulu, a luxurious wellness spa here that offers “miracle anti-aging” IV drips, saunas, cold plunge pools, and red light therapy beds. Alysha trained as a nurse but quickly realized during the early days of the Covid-19 pandemic that she wanted to pursue a career in wellness. The sisters are, like many Americans, taking stock of MAHA — however one defines it — and arriving at divergent views while trying not to let that separate them. Alysha, who said she is apolitical and does not vote, learned of Kennedy in the past year and was intrigued by his backstory as a public interest lawyer (and his gravelly voice). She’s become interested in many of his arguments since. “Maybe some could label me a conspiracy theorist, but I’m open to learning,” she said. “And yeah, a lot of our industry’s keeping us sick. And that’s why I went holistic.” She has over time become skeptical of the safety of Covid vaccines and flu shots — notably, side effects such as Guillain-Barré syndrome, which remains extremely rare — so she opts out of both. Amber, on the other hand, recognized the value of vaccines after she had a baby during a brutal flu season. With a naive immune system and months to go before he could receive his first vaccines, her son was at higher risk of developing a severe fever. If that happened, he could have been hospitalized, and medical protocol would’ve called for a spinal tap to test him for infection, she was told. “Knowing that I held the keys, in a way, to preventing that … I’m just going to make sure that what I’m doing is protecting my baby,” she said. Advertisement She asked all family members to have updated shots against flu, tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis before meeting him. If they didn’t, they had to wear a mask, as was the case with Alysha. “As a new mom, I think you’re just—,” Alysha said. Amber cut her off: “Overwhelmed? And terrified?” Amber initially liked the idea that MAHA was questioning the status quo, but some of the administration’s decisions, like cutting funding for scientific research and federal health agencies, feel “dangerous,” she said. She also worries about the long-term impacts of the president and health officials tying vaccines to autism — an assertion that Kennedy has long promoted but that has been disproven in large trials involving hundreds of thousands of children around the world. “A conversation was started, and it hasn’t been finished,” she said. At this point, “people are talking past each other.” A city that embraces free thinkers In some ways, Texas’ turn to MAHA has been a long time coming, starting in its capital: Austin. Beyond the state’s conservative bona fides, the city has long had a reputation for doing things its own way — and an overall high quality of life — that in recent years attracted tech workers and other wealthy Californians fleeing liberal politics and income taxes. Many descended on Austin during the Covid pandemic. “There’s a lot of free thinkers in Austin, on the left and the right,” McCormick said. Health policy, which historically coded as a liberal priority, hasn’t been a major focus in the capitol. But once MAHA’s star began to rise last summer, McCormick, a former chief of staff to the Texas railroad commissioner, saw an opening. His own experience with relatives’ health troubles had shaped his views. His mother, who had dealt with alcohol use disorder, had a stroke in 2012 and was disabled, making McCormick her caregiver; his father died from late-stage lung disease. “I’ve just seen how cookie-cutter it is,” he told STAT, explaining the ways in which health care has become depersonalized. “I’m not under some delusion that government can fix all this,” he said, but he saw in MAHA a rare chance to make health care a bipartisan issue. Advertisement In the next legislative session, Make Texans Healthy Again will pursue bills that failed this year, like proposals to ban fluoride in drinking water, license naturopathic doctors, and expand nurse practitioners’ scope of practice. Beyond that, the group will soft-launch some new ideas, too: pushing schools to prioritize fresh fruit and making sure no bills protecting pesticide manufacturers get passed, McCormick said. The pesticides bit is “the most divisive piece,” he admitted. While Trump’s environmental regulators have taken a relaxed approach to health hazards like pollution and agrochemicals, MAHA has been calling for a tougher stance on herbicides like glyphosate, which is used in food production. Ideologically, McCormick’s priorities, like MAHA’s, are an odd mix. Some public health experts would likely take issue with the anti-fluoride and pro-meat bills, while celebrating more fresh produce in schools. Austin is itself a place that embraces such fluidity. The matcha-sipping yogis, spiritual slackliners, and buff entrepreneurs bonding in saunas all tend to share a certain streak — individualistic, and politically mutable. In this way, they take after one of Austin’s most famous residents: Joe Rogan, who moved to the area in 2020. In five years, the podcast star has, in small but notable ways, further transformed the local culture. Many other charismatic and controversial figures have ties to the area: biohacker Dave Asprey, anti-vaccination activist and former Kennedy communications director Del Bigtree, the organ meat influencer “Liver King,” wellness entrepreneurs Aubrey Marcus and Mark Hyman, Whole Foods co-founder John Mackey, and HumanCo’s Jason Karp, whose brands make pizza and ice cream for the health-conscious. Marcus hosted a fundraiser for Kennedy in Austin when the secretary was running for president. Austin is the birthplace of Texans for Vaccine Choice, a powerful political action committee opposed to vaccine mandates — and one of the first such PACs in the nation. It’s where similar groups have gotten organized, accrued real power, and polished tactics they can deploy around the country. (Children’s Health Defense, the nonprofit Kennedy founded and led for years, is hosting its annual conference in Austin later this month.) Advertisement As a result, it’s only become harder for public health advocates to pass favorable legislation in the state, or get lawmakers to offer full-throated support for vaccination. “Really, the nation has just caught up with what we’ve been dealing with in Texas for the past 10 years,” said Rekha Lakshmanan, chief strategic officer for The Immunization Partnership, a nonprofit group that promotes vaccination as a public health strategy. A December 2024 poll found 72% of Texans thought the government should require parents to vaccinate their children. At least 70% of respondents thought vaccines were safe and effective. Those numbers are still pretty high, but have slipped as hesitations about the Covid vaccine led some people to begin questioning all shots, Lakshmanan said. On visits to communities, Lakshmanan says she most often gets questions from parents about where to get their children vaccinated. There is very little of the combative tone that dominates online discourse about vaccines, especially under Kennedy. A distrust of mainstream medicine If MAHA is about helping people to live healthier lives, that doesn’t necessarily mean the same thing to everyone. Take the question of how people manage their chronic health conditions. In a bougie Austin community, a cash-only clinic lets members, for about $300 per month, get quarterly blood tests and then have their plasma replaced with the crystal-clear human protein albumin. The center, called Humanaut, also offers IV drips, personal training, full-body workups, “electromagnetic field therapy,” and vibrating chairs to stimulate the nervous system. Health care is leaning this way, at least for the rich. One year in, Humanaut has already opened a second clinic in Palm Beach Gardens, and is planning a third in Dallas. People “don’t just want to go sit in a waiting room that’s dirty. They want it to be personalized. They want it to be chic,” said Shelby Fitzgerald, director of training and development at the Austin location. Those who can’t afford to upgrade their health care are shifting their practices in smaller ways. Advertisement Army veteran Carlos Miller, 52, started stripping harsh chemicals and preservatives from his daily-use products after reading that they could interfere with medical treatments or accelerate chronic conditions. Miller has high blood pressure, and is trying to manage it without medication. His doctor recommended an ACE inhibitor, but Miller got spooked once he learned the commonly prescribed medications were developed in the 1970s from a compound found in snake venom. “It’s like you’re having a snake bite you every day to lower your blood pressure, and that didn’t sit well with me,” he said. His doctor never counseled him on natural or lifestyle-based alternatives to the medication, Miller said. He got off the pills without talking to his physician about it. He didn’t see the point. “I’m not discounting or discrediting any medical professionals, but they got a job to do, and they’re gonna do it inside of the confines of their own thinking. So they’re gonna push the pill on you first,” he said. “It’s money in sickness.” Carolina Martinez, 70, has had her own chronic health issues. Diagnosed with type 2 diabetes — a condition she had never heard of — three decades ago, she’s still resisting doctors’ attempts to get her on insulin. She takes the medication metformin and tries to avoid foods that spike her blood sugar, like soda, flour tortillas, and rice. Her care is, by her estimation, not great. She shares Miller’s skepticism of health care professionals. “We all know it: Doctors are just money, just money. We are numbers, numbers for them.” None of her physicians have checked her legs or toes, she said, as is custom for diabetic patients since they are at higher risk of leg ulcers and amputations. She requested a referral to an eye doctor, since diabetes puts her at higher risk of glaucoma and other problems. “And the eye specialist always tells me that I’m fine. And I, in the meantime, get more blind,” she said, laughing. Martinez, who emigrated to the U.S. from Mexico in 1974, is retired and on Medicaid, “gracias a Diós.” Lately, she’s been watching a teacher on Facebook talk about how interpersonal conflict can lead to disease. She’s trying to avoid arguments with her husband to see if it will help. Advertisement Idalia Medina’s online searching has made her tighten her grip on her five children’s health care. She works at a day care facility and her children are on Medicaid, so the family receives $148 each month in SNAP benefits. It doesn’t go very far, but she still prioritizes healthy foods. Her son Matthew was diagnosed with autism about six years ago. Upon reading the claim that vaccines can cause the condition, she decided to delay vaccinating her children — against the advice of their pediatrician. (She also now avoids artificial food dyes, after reading that they can trigger behavioral changes.) “I didn’t want to go through the same thing with my other kids,” said Medina, 35. With Matthew, “there was a lot of evaluations, a lot therapies, and I had to move work. It was just so much, mentally. And I was just like, I can’t do this.” She hadn’t heard of Kennedy or MAHA, but she did hear the Tylenol claims. Since she gives her children acetaminophen for fevers, the news made her scared again. “Wait, is it going to do it to the other kiddos?” she said. Cowboy mentality meets MAHA Worries take on a different shape in the tiny, rural towns that make up much of Texas. Alfredo Shirley, 73, brings in a meager living in Bandera, selling roadside plates of barbecued chicken and brisket. Decades of hard physical labor, including loading cow carcasses onto hooks for processing, have left him with a damaged knee, shoulder, and back. He’s had a half-dozen surgeries in the past year, including on blocked arteries in his legs. Because of all the procedures, Shirley got on Medicaid. If he had to guess, it all cost over $150,000. Earlier this year, he developed a serious infection in his knuckle, he thinks from a venomous spider bite. Left untreated, his skin deteriorated to the point where his knuckle bone was protruding, and his middle finger turned black. He nearly lost it, Shirley said. He went twice to the hospital in Austin, a two-hour drive away, and ultimately to Houston Methodist, nearly four hours away, to get treated. People in rural Texas know these kinds of problems so well it can become a cowboy maxim: Rub some dirt on it. Even 30 minutes outside of Austin, Bastrop mayor Harris worries about how long it would take for an ambulance to get through congested Highway 71 traffic and to a major hospital during rush hour. There is a small hospital with an emergency room, and an urgent care center nearby, but Harris said it’s not sufficient. His small city has a large population of older adults and veterans who often have to travel at least half an hour to a VA facility for specialty care. It’s the same conundrum for people with serious injuries or illnesses. One of Harris’ friends, whose son has sickle cell disease, has to go to Austin for his doctor’s visits or bad pain crises. “People who work locally don’t make that much amount of money,” Harris, 44, said. “If you’re having to travel the road two, three days a week, you start having to make sacrifices.” It is challenging to envision how MAHA, which is still young and ill-defined, will play out in a populous, complicated state like Texas. Even the effect of MAHA-backed laws will depend on how they are implemented. Physical activity requirements, for instance, vary by school district. McCormick of Make Texans Healthy Again doesn’t want the movement to be overly zealous or prescriptive at the expense of being practical. The legislation he helped pass could drive major change in a decade if handled well, he said. By then, his daughter, now 2, will be a preteen — and a case study. “I’m just trying to make sure I give her the best opportunity to succeed,” he said. The fate of Texas’ other 7.5 million children, and whether they usher in a healthier future for the state, is yet to be determined.