By Patrick J. Walsh

Copyright ncregister

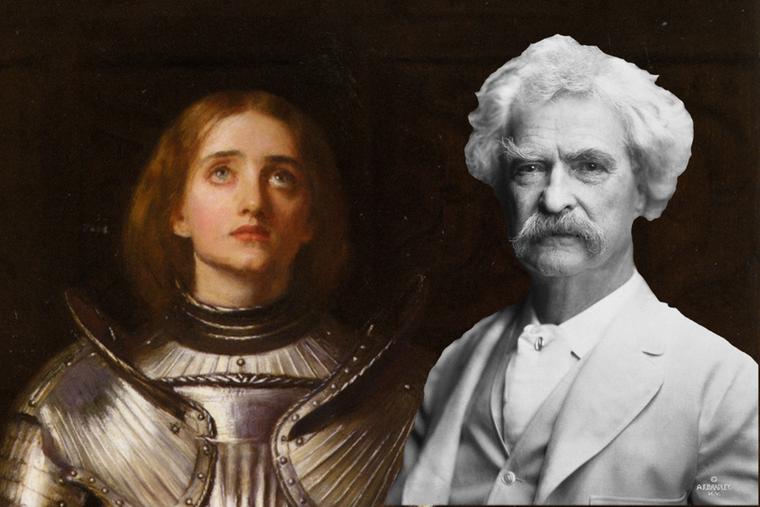

When he was a boy walking the streets in Hannibal, Missouri, pages from a biography of Joan of Arc (1412-1431) were swept up to Samuel Clemens’ feet.

Upon reading the strewn pages, Clemens inquired of his mother whether Joan of Arc was a real person or a myth. As biographer Ron Chernow writes, “The chance finding was the catalyst for Twain’s lifelong voracious passion for Joan.” He studied the trial of Joan of Arc and thought that it was “the most thrilling historical document he had ever read.”

The man who scoffed at the Christian faith wrote an excellent novel in admiration of Joan of Arc. In fact, Twain, a lifelong admirer, studied the saint’s life for 15 years.

In the fall of 1892, when the Missouri native was by then known as Mark Twain, his wife and daughters urged him to write more serious work. They feared his reputation as a coarse stage humorist was destroying the serious writer. So Twain started to write a new fast-paced, structured novel — one that he would declare was his favorite book. As he wrote: “I like Joan of Arc best of all my books; and it is the best; I know it perfectly well. And besides, it furnished me seven times the pleasure afforded me by any of the others; twelve years of preparation, and two years of writing. The others needed no preparation and got none.”

Personal Recollections of Joan of Arc was published in 1896 and is considered one of Twain’s best works. It was republished by the Library of America in the 1990s.

Twain loved the history of the Middle Ages. Joan of Arc appealed to his sense of chivalry and belief in adolescent purity. Joan, a teenage peasant girl, heeding the voices of saints, saved France from English occupation.

With unshakable faith and great courage, she won several key victories against the English before being captured by them and burned at the stake. She was canonized by the Church in 1920.

Twain was amazed that Joan became, at age 17, commander-in-chief of a national army.

“With Joan,” Chernow writes, “Twain set aside his worldly cynicism and wrote in worshipful terms, making no attempt to debunk her saintly nature. His searing skepticism about religion vanished as he venerated a young woman guided by voices and visions from God.”

Twain recounted how, in the fields where Joan tended her sheep, St. Michael appeared to her in a vision and divinely appointed her to command the armies of liberation.

The supernatural radiance emanating from Joan spread like wildfire, inspiring France. Her enormous popularity and military skill led to the creation of the French state. As Winston Churchill once wrote, “Joan was a being so uplifted from the ordinary run of mankind that she finds no equal for a thousand years.”

Twain’s novel powerfully describes Joan’s martyrdom on May 30, 1431.

At 9 a.m., the “Deliverer of France” was forced to wear a miter cap inscribed, “Heretic, Relapsed, Apostate, Idolater.”

On the way to the stake where she would be burned, Twain relates how the crowd “sank to their knees praying, and many of the women weeping; and the moving invocation for the dying rose again, and was taken up and borne along, a majestic wave of sound, which accompanied the doomed solacing and blessing her all the sorrowful way to the place of death.”

Many of Twain’s literary heroes, of course, were adolescents like Joan of Arc: Tom Sawyer, Huck Finn, Tom Canty and others in The Prince and the Pauper.

‘Emblem of Americana’

Chernow’s new biography of Twain, which highlights his esteem for the Maid of Orléans, is almost 1,200 pages long, but it’s never tedious. Its heft is fitting for someone Kipling called “the largest man of his time” and whom many, including Chernow, consider as “an emblem of Americana.”

The book is almost a day-by-day account of Twain, but it’s no mere diary; it’s an engaging narrative filled with pertinent comments and insights into this extraordinary man.

Today, most people remember Mark Twain as the author of The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and (maybe) Life on the Mississippi. These were indeed his best works.

Samuel Langhorne Clemens, born in Florida, Missouri (1835-1910), published more than 30 books, thousands of newspaper and magazine articles and 12,000 collected letters. His oral output as America’s “foremost talker” on the lecture circuit is as extensive as his written work.

Clemens belonged to an America rapidly reconstructing itself from an agricultural community into an urban one. Between 1897 and 1911, U.S. disposable income doubled. This new, vibrant America became synonymous with money, worldly success and fame, which Twain craved.

During the Gilded Age, many Americans lost faith in a supratemporal reality. Darwin and science seemed to have made a monkey out of man. Edison’s incandescent light shed light on the temporal things of the world, but the age shed little light on permanent things or on things divine. We still live in a gilded age.

In Light of Franklin

Twain reminds one of Benjamin Franklin, another quintessential American, who also worked as a printer apprentice to his brother. Moreover, Franklin, like Clemens, became a great writer known by a pseudonym, “Poor Richard.” Clemens adopted the pen name “Mark Twain,” which was a form of measurement gauging the depth of the Mississippi River that Twain often heard shouted when he was a steamboat pilot.

Additionally, both Franklin and Twain were intrigued by inventions, adhering to the new faith in material progress. Franklin once said that “the invention of a machine or the improvement of an implement is of more importance than a masterpiece of Raphael.” Twain likewise told his sister that inventors of mechanical devices were the “highest order of poets.” Both men were tireless self-promoters, loved the limelight, had great wit, and were dismissive of Christian faith.

Chernow’s biography points out the many contradictions of Twain, who coined the term “Gilded Age.”

“Twain raged against plutocrats … yet strove to become one. A compulsive speculator and a soft touch for swindlers. He spent a lifetime chasing harebrained schemes and failed business ventures.”

It’s ironic that Twain’s wealthy society wife, Olivia Langdon, called him “Youth,” for, in many ways, he remained a stunted adolescent.

A faithful husband, Twain loved his wife and family, could be generous to friends, and financially supported aspiring artists and others in need.

The former steamboat pilot of the Mississippi, sadly, did not learn the deeper lesson of human existence. Unlike Joan of Arc, Twain could not accept the reality of human suffering, the tragedy of life or the redemptive meaning of the cross.

Mark Twain’s books engage pathos over tragedy, a pathos of arrested development. He lived in a sentimentalization of reality, including in his books the heavy presence of nostalgia which, when indulged, gives rise to self-pity.

Twain’s birth coincided with the appearance of Halley’s Comet. Twain remained fascinated by the event for the rest of his life. In 1909, he predicted: “I came in with Halley’s Comet in 1835; it’s coming again next year [in 1910], and I expect to go out with it. It would be a great disappointment in my life if I don’t. The Almighty has said, ‘Now here are these two unaccountable freaks; they came in together, they must go out together.’”

Mark Twain died on the night of April 21, 1910, at the age of 74, as Halley’s Comet shone in the evening sky.

MARK TWAIN

By Ron Chernow

Penguin Press, 2025

1,174 pages, $45

Patrick J. Walsh is a writer in Quincy, Massachusetts.