By Dewey Sim

Copyright scmp

Indonesian President Prabowo Subianto had a last-minute change of plan when he travelled to Beijing to attend China’s military parade in Tiananmen Square, just hours before it began.

Prabowo had earlier decided to cancel the trip because of widespread protests at home.

But he showed up for the parade in a grey suit on the morning of September 3, taking a seat at the rostrum beside Russian leader Vladimir Putin, who was to the right of Chinese President Xi Jinping.

Sources said the Indonesian leader arrived only hours before the parade started and he had to stay in a different hotel from his team because the one designated for Asean delegations was so full that not a single room was left.

Prabowo’s office said he had decided to go ahead with the trip after receiving an “urgent request” from China to attend the parade. The office also said the visit was to “maintain good relations with the Chinese government”.

Prabowo was among a strong contingent of top leaders from Southeast Asia – a region Beijing has been courting – at the parade that showcased China’s rising military strength and growing global influence.

Their attendance was a show of support for Beijing and a clear message to Washington that the region has alternative partners as they face mounting pressure from sweeping US tariffs, according to analysts.

They said while Southeast Asian nations were increasingly looking towards China and their appearance at the parade reflected a tilt away from Washington, regional ties still hinged on Beijing’s approach to contentious issues such as the South China Sea disputes.

The world may have had its attention fixed on Xi, Putin and North Korean leader Kim Jong-un, who were seen together for the first time at the parade, but it was hard to miss the Southeast Asian presence. The parade – marking the 80th anniversary of the end of World War II – was skipped by the United States and most European countries.

From Southeast Asia, besides Prabowo, the event was attended by Malaysian Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim, Vietnamese President Luong Cuong, Lao President Thongloun Sisoulith and Cambodian King Norodom Sihamoni. Myanmar sent Min Aung Hlaing, the acting president, while Singapore was represented by Deputy Prime Minister Gan Kim Yong.

That high-level representation was an upgrade from 2015, when China held its first Victory Day parade. Earlier this month, most of the Southeast Asian countries also sent representatives to the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation summit that was held in Tianjin days before the parade.

Benjamin Ho, an assistant professor at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies in Singapore, said the strong turnout from the region was partly because Southeast Asian nations could agree that they were victims of Japanese aggression during World War II.

But he said it was also a demonstration to Washington that the region has other partners, like China, at a time when US President Donald Trump is waging a tariff war.

“Southeast Asian countries are aware that being seen attending this parade with China is almost like a form of reminder to the United States that we’ve got a Chinese alternative … to show that Southeast Asian countries are not without agency should we choose to demonstrate support for Chinese initiatives,” Ho said.

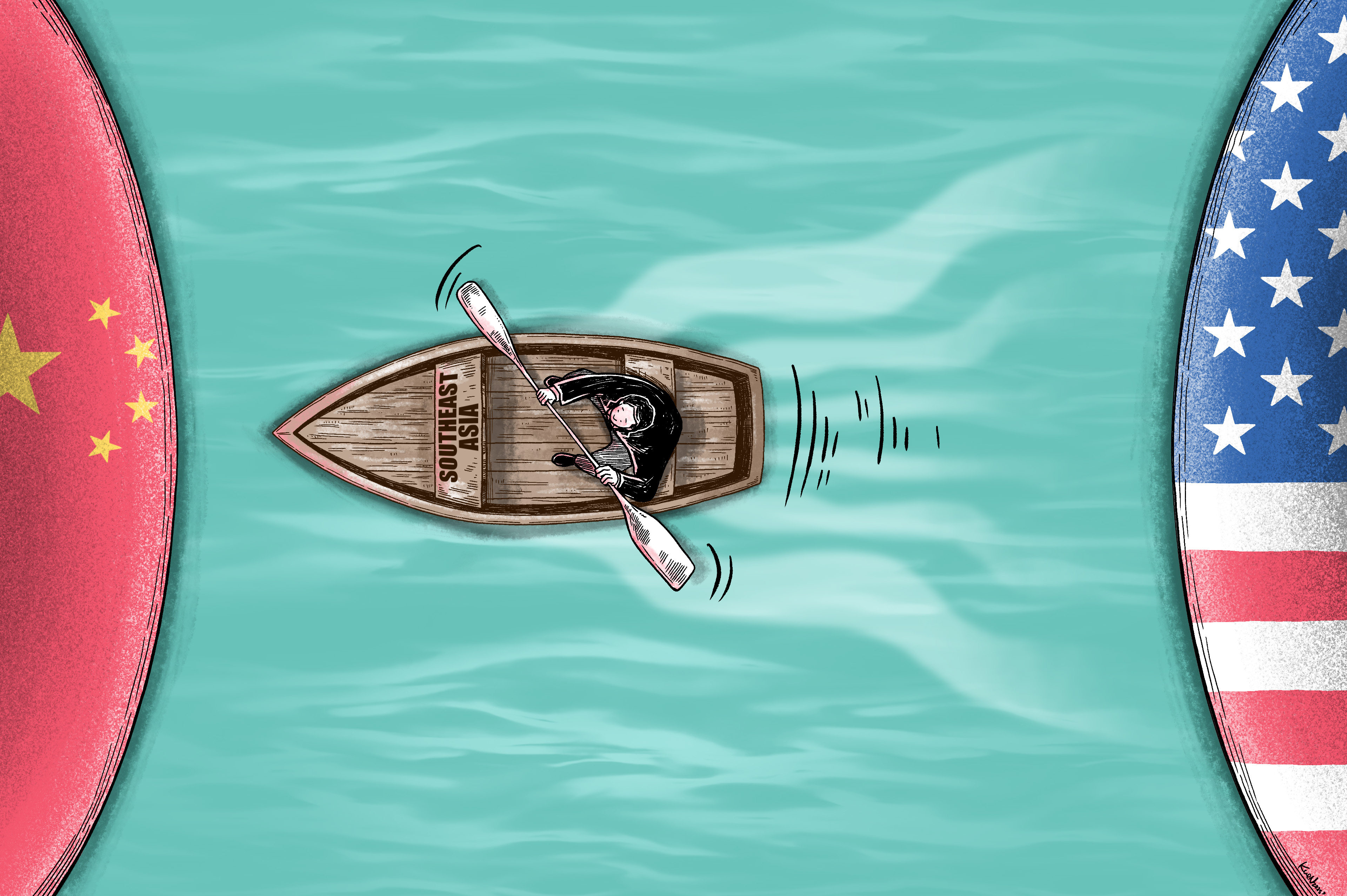

Southeast Asian countries have found themselves increasingly caught in the deepening superpower rivalry between the US and China, with leaders stressing that they would not be forced to take sides.

But the region’s economies are among the hardest hit by Trump’s so-called reciprocal tariffs. Beijing, in contrast, has been rallying countries to stand up against protectionist measures, painting itself as a reliable partner that would defend the international order.

Xi made China’s position clear at the SCO summit in Tianjin, telling leaders – mostly from developing economies – that “hegemonism and protectionism continue to haunt the world”.

“We should continue to dismantle walls, not erect them. We should seek integration, not decoupling,” he said.

“We should continue to unequivocally oppose hegemonism and power politics, practice true multilateralism, and stand as a pillar in promoting a multipolar world and greater democracy in international relations.”

Ho said the Chinese leader’s speech would have resonated with Southeast Asian nations facing hefty tariffs from the US, and that it “dovetailed well with China’s own proclamation that it is responsible”.

He said Southeast Asia’s attendance at China’s diplomatic events this month indicated that the region was showing “some kind of symbolic support” for Beijing, “to let the Chinese know that Southeast Asian countries are happy to lend our support as long as the policies are not against us”.

“This is also a way of reminding the United States that if you don’t want to court us or if there is some kind of benign neglect or worse hitting us with all these tariffs then there are always alternatives,” Ho added.

“It gives you a sense that indeed we are tilting [towards China] if the US continues its current policies.”

According to Wang Yiwei, director of the Institute of International Affairs at Renmin University in Beijing, countries in the region “have grown disappointed with … the US-led globalisation system, especially because of the trade war and tariffs”.

“As a result, they are increasingly looking eastward by participating in events like the SCO summit and China’s military parade,” he said.

“In Southeast Asia, in terms of both hard and soft power as well as influence, China has surpassed the US in recent years.”

Wang also noted that China was the “economic engine” of the region.

He said: “For many participants, attending the parade was not just about commemorating World War II but also about recognising that China, not the US, may represent the future of global leadership.”

During talks with the visiting Southeast Asian leaders in Beijing this month, Xi sought to drive home the message that China would further cooperation with the region and champion the rights of the developing world.

In a meeting with Prabowo, Xi said China and Indonesia, as major countries of the Global South, should “jointly oppose unilateral bullying”. Speaking with Malaysian leader Anwar, Xi said greater efforts between China and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations were needed to safeguard the interests of the Global South.

Jonathan Ping, an associate professor at Bond University in Australia, said Southeast Asia’s upgraded representation at the parade signalled “growing tolerance for China’s self-proclaimed leadership role” and a short-term pragmatic response to counter Trump’s “America first” policies.

He said it was also a “pragmatic recalibration” by Southeast Asian states resulting from China’s military expansion, deepening great power conflict and Trump’s tariff policies.

“Leaders are rightly engaging with China’s economic and strategic overtures, viewing China as much a threat to their own stability and prosperity as Trump’s unpredictable trade policies and yet they must submit to the imposed brutishness of the great powers,” he said.

For China, Ping expected Beijing would seek to use Southeast Asia’s participation in its events to validate its leadership narrative and portray it as a “symbolic endorsement of its regional influence and a rebuke of ‘Western’ dominance”.

Peter Mumford, Southeast Asia practice head at consultancy Eurasia Group, said while the turnout from the region last week suggested a desire to strengthen ties with Global South countries, including China, amid Trump’s tariff pressure, the role of the US leader’s policies should not be overstated.

He noted an existing push by the region to deepen ties with the developing world, including Indonesia joining the China-led Brics and Malaysia and Thailand seeking to join the grouping, prior to Trump’s tariffs.

“The military parade in China was a special anniversary event. It is completely unsurprising that, once invited, many Southeast Asian leaders wanted to attend a major event like this in China, given close economic ties,” he said.

But even as Southeast Asia appeared to show strong diplomatic support for Beijing, analysts said there were still pain points beneath the surface that hindered the region’s ties with the Asian giant.

Ping said with the events China hosted earlier this month it had attempted to position itself as a counterweight to Western influence and offered the region a vision of multipolarity, sovereignty and shared development.

“But President Xi’s attempt to reinforce China’s role as a stable, long-term partner by promoting economic integration, infrastructure development and ideological solidarity is undermined by daily conflict with Asean states in, for example, the South China Sea,” he said.

“China’s intent is to reshape the regional order on its own terms, leveraging misplaced trust, trade dependence, and tailored bilateral relations over multilateralism.”

Tensions between China and Southeast Asia involving overlapping claims in the South China Sea have worsened in recent years, particularly between Beijing and Manila. Beijing claims almost the entire resource-rich waterway.

Ho in Singapore said he would describe Southeast Asia’s approach towards Beijing as “cautiously supportive” given territorial disputes in the South China Sea.

“It’s not just about the banquets and lavish ceremonies. A lot also depends on how the Chinese actually, on the ground, operationalise their diplomacy with Southeast Asian countries,” he said.

“It’s no point inviting the leader of Vietnam over [to China] only to have a conflict over the Spratly Islands the next day,” Ho added.

“[Southeast Asia] is realistic enough to recognise that we don’t want to be excluded from China. But we are also going to see what China does after the military parade is over.”